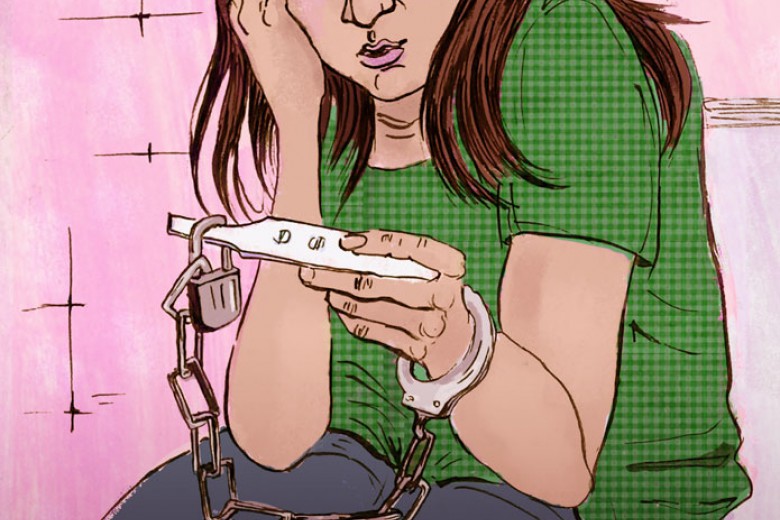

Back in 1983, Canadian legislators replaced the word “rape” with the three-tiered designation “sexual assault.” The hard-won laws also scrapped the paternalistic requirement of corroborating evidence for rape allegations and prohibited references to survivors’ sexual history.

The Globe and Mail marked the 30th anniversary of this landmark reform with an exposé asserting that current laws “violate rape victims,” since low conviction rates (one in four cases) compel police to discourage survivors from charging above the lowest tier – which now accounts for 98 per cent of charges.

Meanwhile, the protracted stress of legal action has compelled anti-violence advocates and crisis workers to discourage laying charges at all. Today, 90 per cent of assaults are never reported in Canada, where a woman is raped every seventeen minutes.

At first glance, the history lesson is simple: the law has limits and feminist struggle must exceed the courts. When one considers the hundreds of missing and murdered Aboriginal women, the police and courts’ vile response to the ordeals faced by people like Rehtaeh Parsons and Audrie Pott, or the defense raised on behalf of the self-described “rape crew” in Steubenville, Ohio, there’s little wonder that the anniversary of the 1983 legal reform passed with little more than pained reminders to stay the course.

But we’d be remiss not to take away more this time.

When the Globe and Mail sought explanations, it landed on a word problem: “Today, those trying to understand why reforms have backfired begin with the word rape.” The article tried to revive debates about language tactics, suggesting that “sexual assault has become ‘kind of a soft phrase – a joke used by people who want to be dismissive.’”

For many, it’s difficult to accept that persistent sexual violence owes more to a legal word change than to the astounding flexibility of patriarchy. Even the Globe and Mail published a rejoinder that highlighted the law’s limits and urged social movement action against rape culture.

But if it’s true that our lexicon isn’t conveying what we intend, what’s our next step? After all, law and policy are moving parts of the intricate thing we call culture. Consequently, changes to law and policy are connected to transformations in the political sphere and – by extension – to shifts within language itself.

In grassroots feminist discourse, the term “sexual assault” is left intentionally and virtuously broad to encapsulate a wide range of offenses. Many political concepts are strategically placed in this precarious spot where clarity and openness overlap. Consider the persistent debates about the meanings of community, solidarity, and accountability within contemporary feminist struggle.

The words may appear self-evident, but each can become a minefield. Unsure of what exactly it is that we as feminists mean, it can be difficult to communicate with others. So we’ve become tolerant of our differences and have learned to foreground the perils of insider language. Still, how do we proceed when the meanings of words change before our eyes?

It’s tempting to insist on specific definitions. We could respond to dismissive uses of “assault” as hateful mischaracterizations. Alternately, we might propose adopting new words as our feminist predecessors did. In this vein, the Globe and Mail article reasoned: “Maybe we need words like ‘rape’ – with its power to shock – back in our legal lexicon.”

But history teaches us that words – even “our” words – don’t have fixed definitions. Nor can we count on the subcultural expressions we coin to gain broad currency. A word’s resonance changes along with the contradictory demands of the moment in which it’s uttered.

Because earlier and later senses of words often coexist, struggles over the meaning of words can provide a snapshot of the broader social landscape. When we engage in these struggles, we’re also making a claim about how the social contradictions we confront should be resolved.

Against the backdrop of pervasive, devastating violence, such a claim is bound to rub some activists the wrong way; we understandably prioritize practical questions (What’s the best word for the campaign?) and dismiss further deliberation as semantics. Nevertheless, word debates like those initiated by the Globe and Mail demand that we neither falsely divide such discussion from the history of doing nor imagine that shifts at the level of words will resolve our political problems once and for all.

We should seize hold of these fights over words to determine what they convey about our current political moment. The feminist poet Adrienne Rich said that “a language is a map of our failures.” Such a map is painful to look at and difficult to read. However, it remains indispensable for charting our course.