Catherine Dubé noticed something strange on the first day of picketing Simon Fraser University’s (SFU) Surrey campus: two men in plainclothes watching, taking pictures, and filming picketers.

The following week, twice as many men showed up. Picketers speculated that the men worked for the mall next to SFU’s Surrey campus, but when they saw the same men at a picket on the Burnaby campus, that theory fell apart.

“The only thing I was pretty sure of was that they were definitely there to film us and surveil us,” says Dubé, a PhD student and lead organizer for the Teaching Support Staff Union (TSSU). As the days passed, she noticed the men getting closer to picketers and sometimes standing in the way of the marching line. When one of the men engaged a picketer in conversation, he refused to identify himself, Dubé recalls the picketer saying.

The university has made a reputation for itself with its poor wages and working conditions, and bad habit of contracting out university services.

“They’re constantly following us,” says Dubé. “International students are getting really concerned [because] they don’t know what kind of information they’re collecting.”

Dubé later learned that the men were from Lions Gate Risk Management Group (LGRMG), which provides “investigation, intelligence, security and protection services” according to its website. The firm has provided security services for the Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline project and surveilled land protectors defending old-growth forests against logging at Fairy Creek, Vancouver Island.

Days after media picked up the story and community members voiced their outrage, SFU announced it had “concluded the contract with LGRMG and will reassess how we support safety on our picket lines going forward.”

This wasn’t the first time – nor would it be the last – that tensions between SFU and organized labour would boil over. The university has made a reputation for itself with its stalling tactics, poor wages and working conditions, and bad habit of contracting out university services – and workers have had enough. They’re reinvigorating the campus’s organizing culture and exposing the university’s antics until all workers are treated with dignity.

Union independence and militancy

The TSSU is known for its especially active and engaged membership, which is due in part to its origins. Originally the Association of University and College Employees (AUCE) Local 6, the local was founded in 1976 during a push to unionize “pink-collar” workers on university campuses across the continent.

Tom MacMillan, a PhD candidate at Concordia University whose research focuses on independent unions and labour democracy, says this era was defined by “feminist syndicalism”: a melding of the women’s liberation movement and the labour movement driven by the idea “that women had to defend their rights in the workplace in order to achieve societal equality.”

Toward the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, many radical independent unions disbanded or joined larger, more mainstream unions with more resources. MacMillan says the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) pitched itself to AUCE organizers and members as a service to members, like an insurance policy, but this view of unions was “very much outside [the] ethos of TSSU where the members are the union and the union only exists because the members participate.”

“The fact that [TSSU is] independent and the fact that they are explicitly political is part of what makes them effective.”

MacMillan says this difference in ideology and the “radical culture” at SFU has kept AUCE Local 6, now TSSU, independent to this day and enabled the union to remain militant and prioritize organizing workers.

One group of workers that has been at the top of the union’s agenda is research assistants (RAs). In 2018, the TSSU committed its resources to organizing RAs and was soon successful: by November 2019, over 900 RAs had signed cards and SFU had signed a voluntary recognition agreement acknowledging the TSSU as the bargaining agent for eligible RAs.

However, after nearly five years of bargaining and labour board hearings, TSSU members say SFU has not honoured the agreement, proposing wages between $17 and $22.22 per hour and offering no health benefits for most RAs in spring 2023.

To top it off, the university argued that RAs paid through stipends and scholarships (over a third of RAs) are students – not workers – and therefore not members of the union. The TSSU tried to resolve this at the bargaining table, but Dubé says SFU doubled down: “They said, ‘this issue is done. You know our position. We’re not debating you on this anymore, not at the bargaining table,’” recalls Dubé. So, the union escalated the issue: “We said, ‘Okay, fine. Let’s go debate it at the [B.C.] Labour [Relations] Board.’”

To bring the issue to the labour board, the union would have to organize research assistants once more. The TSSU held a vote to organize RAs, membership voted overwhelmingly in favour for a second time, and the union launched an organizing drive.

“RA UNION? ASK ME.”

On a bright, sunny day in March 2023, TSSU members and allies from other campus unions gathered in a usually quiet corner on the edge of SFU’s Burnaby campus. People joining the group walked down a long concrete corridor past a boom box playing Bruce Springsteen and a table that had coffee, flyers, and large lime green buttons that read “RA UNION? ASK ME.”

After a few impassioned speeches from workers about the need for a cost-of-living wage increase, the crowd was energized and began marching to the Halpern Centre, where SFU’s board of governors was meeting.

Workers brought with them two paper chains: one yellow, one white. Each link in the yellow chain represented a research assistant who signed a union card in 2019, and each white link a student who signed a petition demanding SFU stop contracting out food and cleaning labour.

As workers carefully wrapped the chains around the concrete building, participants banged pots and pans and chanted “Don’t you F us, SFU!” directly in front of the building’s floor-to-ceiling windows; on the other side of the glass sat SFU’s board of governors.

Members of the TSSU rally on the steps outside of the Halpern Centre on Simon Fraser University’s Burnaby campus during the university’s board of governors meeting on March 30, 2023.

This event was part of a series of creative actions launched by the union to demand that both RAs and contracted-out food service workers be considered employees of the university. In addition to public rallies, a core team of around 30 volunteer organizers were assigned one or two departments to door knock.

In some departments, there was swift backlash to the organizing drive: anti-union managers tore down the TSSU’s posters and spread misinformation about the union. But organizers persisted, rescheduling cancelled events and continuing their postering campaign undeterred.

After less than three months of door knocking, over 1,350 RAs had signed cards. Unlike the 2019 unionization effort, which would have gone to a vote after cards were counted, the TSSU had a recent change in policy on their side: in 2022, the B.C. NDP re-introduced automatic certification, meaning that if 55 per cent of a workforce signs union cards, the union is automatically certified without the need for a vote.

But, just as Dubé and TSSU organizers had predicted, SFU objected once again to recognizing the 800 RAs paid through scholarships and stipends as workers. The university only counted the cards signed by RAs paid through wages, which, despite the union’s efforts, fell just below the threshold for automatic certification. Waged RAs would have to go to a vote.

“They don’t like us, we don’t care!”

Organizing research assistants wasn’t the only fight on the TSSU’s hands; the union was also juggling bargaining for a new collective agreement for teaching assistants (TAs) and sessional instructors. They were hoping to win a cost-of-living wage increase, a pension plan for sessional instructors, and compensation tied to tutorial size. The average tutorial size has shot up from 15 to 25 students (and sometimes as many as 30) since the compensation system for teaching assistants was determined in the 1990s, Dubé says. TAs are paid the same amount regardless of how many students are in their classes.

But SFU was ready for a fight. SFU came to the bargaining table demanding “a number of concessions,” recalls Liam Kennedy-Slaney, a PhD student and chief steward-organizer for the TSSU. Among them were removing the pathway to full-time employment for sessional instructors, axing the portion of pay TAs receive as an untaxed scholarship, and excluding international student TAs from the group health-care plan, which would require those student-workers to pay a monthly fee of $75 to enrol in the province’s Medical Services Plan.

After over six months of bargaining, the university administration was still offering TAs and sessional instructors less than what was offered to other unionized workers on campus. The union took it to a vote, and the nearly 25 per cent of eligible members voting were 91 per cent in favour of striking. They were two weeks away from spring convocation – a perfect opportunity to serve the university with their strike notice.

By prioritizing workers’ conditions and reaching out to those left behind by the university, “people end up caring about the union.”

Two weeks later, a graduating PhD student and TSSU member strode across the convocation stage, accepting their degree in one hand and, with the other, serving the strike notice to SFU president Joy Johnson. Amid eruptions of cheering from the crowd, TSSU members and supporters unfurled a TSSU banner from the balcony. “It was a triumphant moment,” recalls Kennedy-Slaney.

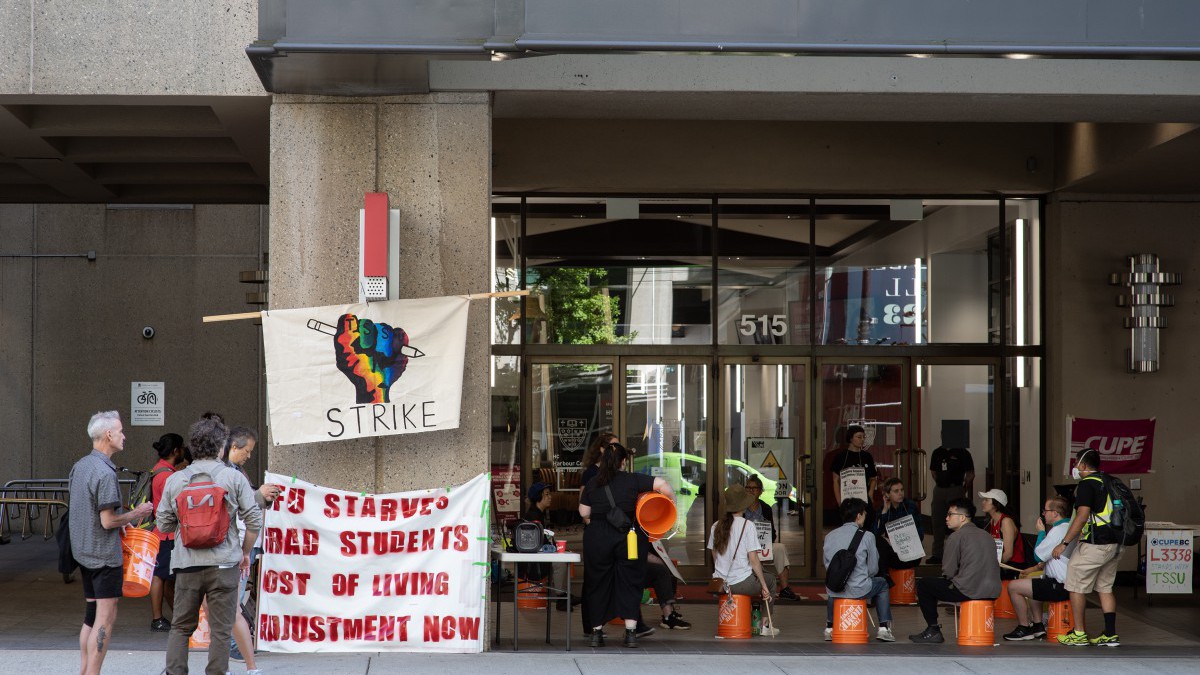

That summer, the union picketed SFU three times. On June 29, the sounds of the TSSU’s picket line thundered throughout downtown Vancouver’s harbourfront. Members wielding drumsticks banged out rhythms on neon orange Home Depot buckets while chanting “Joyless Johnson!” and “They don’t like us, we don’t care!”

In addition to the pickets, TAs and sessional instructors took 10 minutes of class time every week to talk about the strike with their students. According to Dalton Kamish, a fourth-year PhD candidate and a member of TSSU’s contract committee, students were “enormously supportive.” During their first tutorial in the fall 2023 semester, as Kamish was explaining what a union, collective bargaining, and collective agreements are and how little TAs get paid, they recall one student raising their hand and asking, “Why are you still working?”

The wider SFU community also showed overwhelming support for the strike. Members of other unions at SFU, like CUPE Local 3338 and the Simon Fraser University Faculty Association (SFUFA), joined TSSU’s membership on the picket line and the B.C. General Employees’ Union donated $200,000 to TSSU’s strike fund in a show of solidarity.

This kind of solidarity is especially essential for independent unions, says MacMillan. “If you’re an independent union, and you’re established and you have good working relationships with the other unions in your workplace, you can be extremely effective.”

Power struggle at the bargaining table

“Bargaining should follow logic. But, of course, it follows power,” says Kennedy-Slaney.

Despite overwhelming support from SFU’s community, university administration persistently stalled negotiations at the bargaining table with TAs and sessional instructors. Kennedy-Slaney and other TSSU members say that administration wasted hours at the table on typos and punctuation in proposal documents, details that Kennedy-Slaney says the university doesn’t hash out in person with other unions.

“Normally, SFU conducts a lot of these sorts of bargaining sessions over email with CUPE, or with SFUFA, but they choose to bring us to the bargaining table and spend all afternoon doing that,” says Kennedy-Slaney.

“SFU and UBC are both saying that they’re cash strapped, yet at the same time, [they’re using] funding to deny rights to workers at the cost of hundreds of thousands [at minimum] in legal fees.”

So, at a bargaining session in July 2023, the TSSU packed the room as a show of strength and to force SFU’s bargaining team to face not only TSSU’s bargaining team, but a room full of workers. This tactic, called open bargaining, “is a way to pressure the administration,” says Dubé. “It’s a really powerful tool to show that we’re active and we’re listening and we know what’s being done to us.”

Open bargaining is a “very divisive thing in the world of labour,” explains MacMillan. Employers often don’t like the practice, which some believe can make negotiations more difficult for unions. “There’s a connection between how much rank-and-file power members have and whether unions are open to [open bargaining].”

In the TSSU’s case, Dubé says the tactic helped members understand what the TSSU meant when negotiators said “SFU was stalling at the bargaining table.” For example, SFU’s team proposed reducing and removing paid time for TAs to prepare for tutorials, Dubé says. “You can tell they’re a little bit more embarrassed to say things like that.”

Left: TSSU organizer Catherine Dubé takes a break during door knocking for the research assistant unionization effort on SFU’s Burnaby campus on August 10, 2023. Right: TSSU chief steward Kayla Hilstob walks a picket line on SFU’s Harbour Centre in downtown Vancouver on June 29, 2023.

SFU’s bargaining team was not keen on having workers present during negotiations; Dubé says the bargaining team’s spokesperson tried to get some of the workers to leave, supposedly out of concern that having so many people in the room could be a fire code violation.

“The fact that he was concerned was so ironic for the majority of the people in the room because we teach tutorials in rooms where there are not enough chairs for the students,” says Dubé. Plus, the room was well under the capacity limit listed on the university’s website.

A week into the full work stoppage, the TSSU ramped up pressure on university administration. The union picketed every day, rotating between SFU’s three campuses. To further compel SFU to make a deal, the TSSU announced it would picket convocation.

On October 4, 2023 – the day before convocation – the university and TSSU had what Kennedy-Slaney describes as a “surprisingly productive bargaining session.”

According to the university’s 2023 financial statement, SFU spent over $800,000 on fees for one labour lawyer in one year alone.

Kennedy-Slaney says university administration made it clear that having an uninterrupted convocation was important to them and to graduating students, so the TSSU asked if university administration would withdraw their demands for worker concessions and make a deal. Initially SFU declined, but after more back and forth, SFU agreed to do so in exchange for the TSSU not picketing convocation. A couple of weeks later, the TSSU and SFU reached a deal.

Along with wage protections and a pension plan for precariously employed sessional instructors, sessional instructors and TAs’ pay for around 100 online courses was made commensurate with class size. It’s a significant win for the workers teaching those classes – the TSSU has been pushing to tie compensation to class size for years, and this is the first time the union has been able to include those protections in a collective agreement.

TSSU member representative Derek Sahota says the union hopes to broaden this policy to cover all courses taught at SFU. “That leads us to where we need to go in the future: really addressing workload across the board when there’s more students in your class. It’s more work, no matter what course it is.”

The vote and fight ahead

The TSSU’s office is small and the walls are covered in posters, news clippings, and buttons from nearly 50 years of organizing. Members pop in and out, chatting with the folks in the office and sharing what they’ve been working on.

The TSSU office door on SFU’s Burnaby campus

Dubé’s been amazed by how this drive has reinvigorated the campus’s organizing culture. “Sometimes organizing can be a real drag,” she says recalling some of her previous experiences. But in prioritizing workers’ conditions and reaching out to those left behind by the university, she’s found that “people end up caring about the union.”

It’s a difficult thing to pull off at any workplace, especially one defined by short-term contracts and high turnover, as student workers leave once they graduate. MacMillan says that this investment into organizing workers is what makes the TSSU effective.

“TSSU is still one of the shining lights of that sort of labour politics,” says MacMillan. “The fact that they are independent and the fact that they are explicitly political is part of what makes them effective.” “We’ve heard that time and time again and waited years to be able to say this and have a decision made,” says Sahota. “I think that [RAs’] direct experience speaks volumes to what the decision should be: to find that these workers deserve a union.”

By January 22, 2024, RA votes for unionization were finally counted: 93 per cent voted in favour. Almost five years after their first bid for unionization, over 1,000 RAs finally have a union.

“It should not have taken that long,” reflects Sahota in late January 2024. “The delays speak to SFU’s intransigence, trying to beat back unionization.”

However, the more than 800 RAs paid through scholarships and stipends were not included, and weeks later, labour board hearings began to determine whether those RAs were workers.

At the hearings, Sahota says that SFU put forth 17 witnesses, mostly deans and professors at the university, many of whom supported SFU’s claim that RAs paid through scholarships or stipends are students receiving funding to do research as part of their degree, not workers.

But, as Sahota recalls, once the TSSU pushed, many professors described RAs’ tasks, like cleaning beakers and upgrading computer software, which are outside the requirements for the completion of a degree. “We were able to vigorously cross-examine them and that story fell apart.”

The TSSU’s witnesses were all former or current RAs. They argued that research assistants play a vital role in the university’s research program, and without their labour, SFU would not be able to secure grants or produce papers and patents. The TSSU argues that because their work is directed by SFU professors, RAs have an employment relationship with the university.

The TSSU and SFU present their written arguments at the end of May 2024, and Sahota expects a decision from the board sometime in the summer.

CUPE Local 2278, which represents academic workers at neighbouring University of British Columbia, put forward a similar case in early 2024. Both the TSSU and SFU are watching CUPE 2278’s case closely, Sahota says, and SFU’s bargaining team expects appeals for these cases to potentially reach the Supreme Court.

According to the university’s 2023 financial statement, SFU spent over $800,000 on fees for one labour lawyer in one year alone.

“SFU and UBC are both saying that they’re cash strapped,” says Sahota. “Yet at the same time, [they’re using] funding to deny rights to workers at the cost of hundreds of thousands [at minimum] in legal fees.”

It’s been a long fight for Sahota, who has been involved with the TSSU as a member, chief steward, and member representative for well over a decade. He worked as a research assistant in the mid-2010s, long before the RA union effort got started. He says that it’s been moving to see research assistants, particularly international student research assistants, speak about their experiences and attest that what they do is work.

“We’ve heard that time and time again and waited years to be able to say this and have a decision made,” says Sahota. “I think that [RAs’] direct experience speaks volumes to what the decision should be: to find that these workers deserve a union.”