“Politics is nothing else but medicine on a larger scale.”

—Rudolf Virchow, 1848

In Canada and around the world, the health of the poorest people is far worse than the health of the richest – and new evidence suggests we all suffer as a result. In order to address the fundamental unfairness of this situation, we need to completely rethink not just how we do health care, but how we do politics.

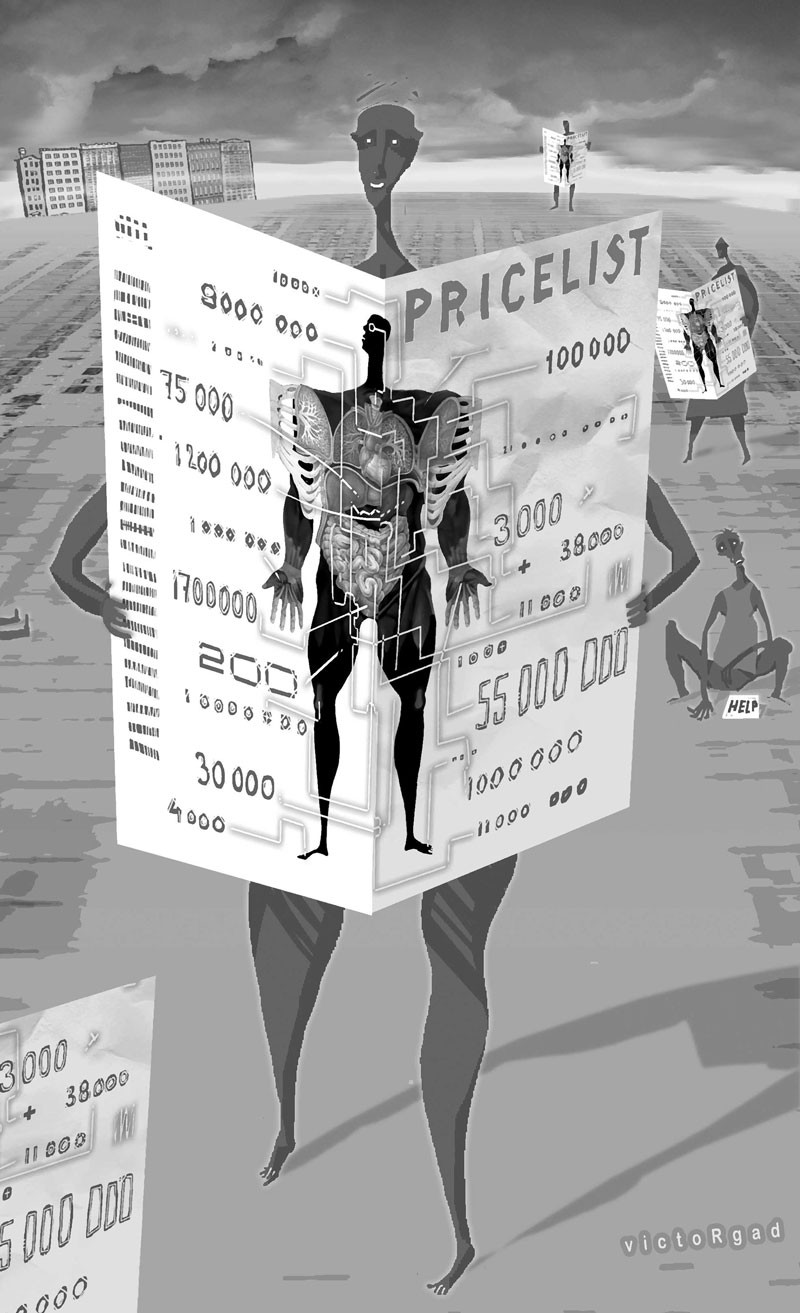

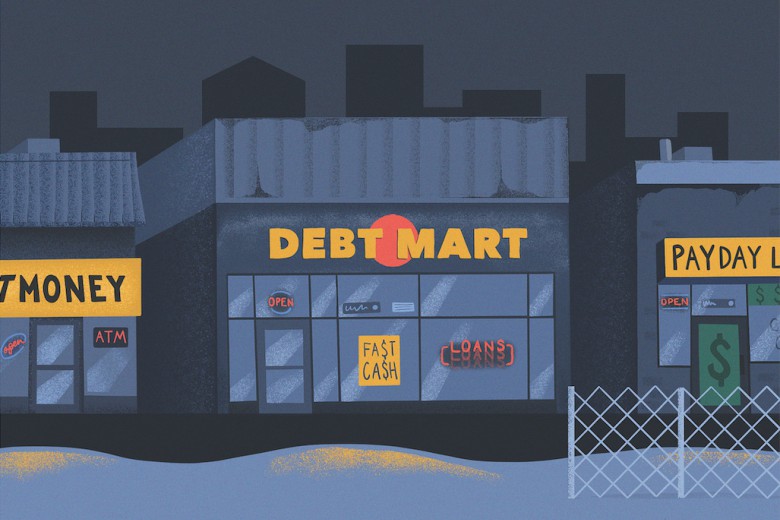

Canada is one of the wealthiest nations on the planet, but the gap between the rich and poor is widening, and rates of child poverty and homelessness are on the rise. Aboriginal people, immigrants and women continue to suffer elevated rates of illness. Epidemics of drug abuse, diabetes, obesity, HIV/AIDS and other diseases closely related to poverty are resulting in lost lives and wounded communities. Meanwhile, human actions are seriously harming the wider environment that supports us; this in turn harms humans. These problems are fundamentally political, but those who raise objections to the current state of affairs, who suggest that there must be a different way of organizing ourselves that is to the benefit of all, are dismissed as naive and ignorant of economic realities. The question before us all is, how can we move beyond this impasse? How can we organize ourselves to make rational decisions for the benefit of all, rather than allow the powerful to raid the commons for their own narrowly conceived self-interest?

The difficulty here is not a failure to understand the extent of our difficulties; it is the lack of a focus, an organizing principle for change. We must state our goals clearly if we wish to reach them. We need a clear objective that will inspire people from diverse circumstances to work together for a greater good.

What I propose is that we have that focus already. It is simply a matter of understanding, articulating and acting upon it. The focus is health: the health of individuals, the health of communities, the health of democratic institutions.

People care about health. It’s part of our assumed common ground, one of our few truly shared values that transcends class, colour and political ideology. Our conversations are rich with references to health. If you ask expectant parents if they’re having a boy or a girl, the answer is inevitably, “we don’t care, as long as it’s healthy.” When neighbours and friends are ill we go out of our way to help them. If people fall on hard times a common encouragement is “at least you have your health.” We speak of healthy relationships, healthy attitudes, healthy economies and healthy appetites. We toast to one another’s health. These familiar expressions reflect our unconscious preoccupation with our common vulnerabilities, hopes and fears: we know, deeply, that health – physical, mental and social – is a necessary condition for the full enjoyment of life.

This preoccupation with health is reflected in public life as well as private – particularly in the heated political debates around health care and health spending. With rare exception in Canada, health care is the number one issue of importance in polling, a rare constant in the tumultuous sea of public opinion. Accordingly, health care spending takes up the largest share of provincial budgets. Many have complained about this, saying that an inordinate focus on health takes away from other important areas such as education, justice and infrastructure spending. In a way they’re right: our focus on health care at the expense of other important areas of public life is disproportionate. But the problem is not that we care too much about health; it’s that we respond to those concerns in an incomplete and reactive fashion. Our approach tends to be palliative rather than preventative; we focus too much on what to do when our health fails, not on how to make sure the conditions are in place for more people to thrive, to stay healthy. If we truly want a healthy society, we need to build a political movement with health as its focus.

Healthy, wealthy and why

I work in the field of health care. My practice as a family physician has taken me to Mozambique, across rural and northern Saskatchewan, and to a deeper understanding of my home neighbourhood of inner-city Saskatoon. These communities have many differences, but they are all marginalized to some degree, are not public priority areas, and as a result their health needs are not met by the current system.

Clinical work in underserved areas offers many joys, but the frustrations are many as well. Every day, no matter what community I’m working in, I see patients whose problems are not merely physical, but political. They stem from lack of safe or appropriate housing, from lack of education, or simply from not having enough money to access the basic necessities of life. It is painfully clear that the problems they face can’t be solved in the clinic or the hospital; rather, they need to be addressed at a much larger level.

The notion that health and illness are determined by life circumstances is not new, and in recent years it has become a staple of health theory and teaching. In one of the first lectures of medical school, students are asked what factors will have the greatest impact on a person’s health. Lifestyle choices are a common response. Others will talk about access to health services, while others guess genetics or culture. After the students weigh in, they are shown the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s list of health determinants, in order of impact.

The Determinants of Health:

1. Income status

2. Education

3. Social support networks

4. Employment and working conditions

5. Early childhood development

6. Physical environment

7. Personal health practices and coping skills

8. Biological and genetic factors

9. Health services

10. Gender

11. Culture

12. Mass media technology (i.e., television viewing and physical inactivity)

Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information

Invariably this list is met with surprise. As aspiring doctors the students think they are in the business of making people healthy. But they discover that the services offered by the health professions barely crack the top 10 factors that influence people’s health.

The lesson to be drawn from the list of determinants, and the one that is stressed to students, is that the most important factors that determine people’s health are social, and the most effective solutions are political. Health services, which respond to the symptoms of ill health, have much less effect on health outcomes than social determinants like income and education, housing and nutrition. What the students learn is that we indeed have the power to heal, but we cannot act alone. The response to illness is not limited to one profession or sector: it must be societal.

The question, then, is where does it make the most sense to focus our political efforts? In other words, which determinants of health are most directly affected by public policy? These social determinants of health are income and income distribution, education, unemployment and job security, employment and working conditions, early childhood development, food insecurity, housing, social exclusion, social safety net, health services, Aboriginal status, gender, race and disability. When we address inadequate housing, when we stop gender discrimination and racism, when we ensure people have access to work that is safe and fair and that our children receive the care and attention they need to grow, then we can dramatically improve health outcomes. So what’s holding us back?

Evidence for equality

The effects of the social determinants on health are readily apparent to those who live and work in underserved communities. They are also supported by studies such as “Health Disparity by Neighbourhood Income,” a 2006 paper published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health.

This study compared the health of the six lowest income neighbourhoods in Saskatoon (according to Statistics Canada) with the same health indicators in the rest of the city. The findings were startling. People in the core are four times more likely to have diabetes, four to seven times more likely to get a sexually transmitted illness and 15 times more likely to have Hepatitis C. Those in the core also experience significantly higher rates of injury, mental illness and coronary artery disease.

When the six poorest neighbourhoods were compared with the city’s six most affluent neighbourhoods, the contrast was greater yet. If you live in the core, you are 15 times more likely to contract a sexually transmitted infection, 15 times more likely to attempt suicide, 35 times more likely to get Hepatitis C, and 13 times more likely to have type 2 diabetes than if you live in the suburbs. With all of these increased risks, a core neighbourhood resident is 2.5 times more likely to die in any given year. The infant mortality rate is three times higher in the lowest income neighbourhoods than in the affluent neighbourhoods.

The starkness of these differences came as a surprise to many. People were embarrassed to discover that in a prosperous city, in the province that gave Canada universal health care, such shocking levels of disparity could exist. And the implications were clear, though politically inconvenient to many: one, poverty and inequality kill; and two, governments that stand idly by are complicit in every avoidable illness and premature death.

If properly considered, this embarrassment and shock could serve as a wake-up call. It could help to refocus our political discourse on the real work of a democracy. A functioning democracy is one in which the government, to the best of its ability, carries out the will of the people and takes seriously its responsibility to serve the best interests of all citizens. Democratic renewal requires a number of things, key among them that people be sufficiently informed to articulate their real needs, sufficiently empowered to present them as demands that can’t be ignored, and sufficiently organized to see the process through to fruition. Democracy is the messy, argumentative, painstaking art of navigating a common course among multiple conflicting priorities. Having some shared framework, some set of guiding principles, can allow these conflicting priorities to be weighed by all in terms of what is best for all.

Health is more than just the absence of illness. The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” What better goal for a society than to ensure that all people enjoy true health – a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being? And what better measure of the success of a government and the society it represents than the health of the people?

If we address the social determinants of health, people will live fuller, healthier lives. This much is clear. And if we are transparent in our intentions, decisive in our actions, and honest in our evaluation of the results, we can foster a common purpose that deepens community, builds solidarity and rejuvenates democracy.

Helping some helps us all

Addressing the social determinants of health doesn’t just help those most in need, but everyone, regardless of social position. This is why the concept is so important: everyone benefits. This approach can be used to reach across divisions of class, race, geography or political affiliation.

In The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett present compelling evidence that the degree to which resources are unequally distributed has a significant impact on the health of everyone. Countries that are more equal, such as Japan or the Scandinavian nations, have much better health outcomes overall than less equal countries such as the United States or Britain. While the ill effects of inequality are certainly greater for those at the bottom of the social ladder, even the wealthiest people in an unequal society are less healthy.

The experience of living in a society with a vast gap between rich and poor damages everyone’s health, resulting in more mental and physical illness, shorter lifespans, greater levels of obesity and higher infant mortality for everyone. Less equal societies suffer more of the social problems that lead to negative health effects, experiencing higher levels of violence, imprisonment, illiteracy and teen pregnancy. Life in a more egalitarian country, meanwhile, benefits the health of everyone, from the least advantaged to the most successful. The editors of the British Medical Journal summarized the implications of Wilkinson and Pickett’s findings beautifully: “The big idea is that what matters in determining mortality and health in a society is less the overall wealth of that society and more how evenly that wealth is distributed. The more equally wealth is distributed the better the health of that society.” Any serious attempt to address health disparities must therefore involve a plan to address not just poverty, but wealth disparity.

Providing everyone the opportunity to improve their lives, to escape poverty and experience the fullness of health, is not just the right thing to do, but also the smart thing to do. It is a delightful coincidence that our future well-being depends not upon our selfishness but our generosity, our sense of justice. The growing gap between rich and poor impoverishes us all, diminishing the quality of life and the health of rich and poor alike. We in Canada consider ourselves a developed country, but to allow the gap between rich and poor to grow is to become less developed.

The dream of a truly healthy society offers us a shared goal with the power to reach across the differences that separate us, allowing us to connect with our neighbours in recognition of our common vulnerability and our common desire to live full and healthy lives. By setting our sights on addressing the determinants of health, we can do both what is right and what is smart. We can improve the health of people and of the political system at the same time.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)