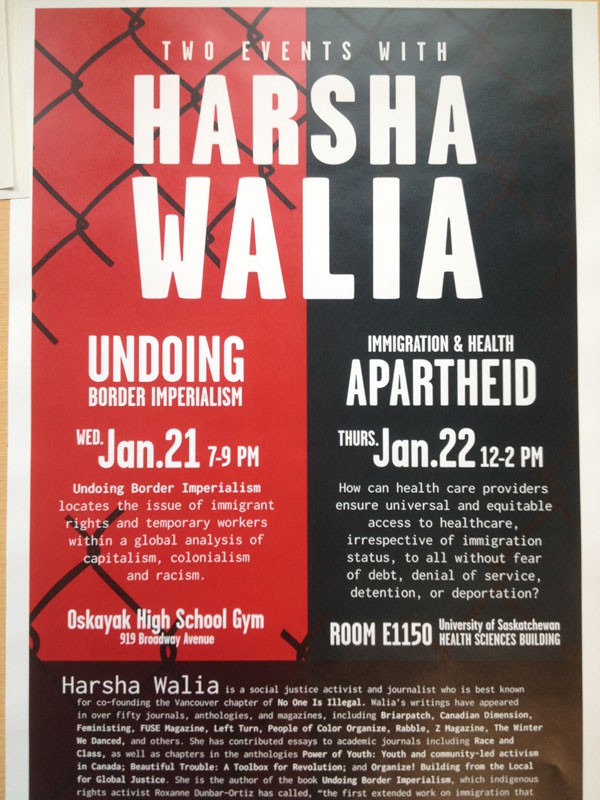

Ryan Meili is a family physician, author, and the founding director of Upstream: Institute for A Healthy Society. He sat down with organizer, activist, and author Harsha Walia to discuss the forces that shape the health of immigrants and refugees, the importance of building alliances with Indigenous communities, and what it takes for people to be empowered.

Ryan: You’re in Saskatchewan today speaking to health science students about migrant justice in Canada. You said that it’s a bit of leap for you, talking to a health care audience like this, that it’s not your usual crowd. But let’s take that leap, through your work with No One Is Illegal, how do you see the issues faced by immigrants and refugees linking to their health and well-being?

Harsha: Whether people are immigrants or refugees, I think most have an overwhelming experience of racism, poverty, and dislocation. And as we know, these are social determinants of health; they impact mental health, emotional well-being, and physical health. We see this manifest in a number of ways, and for many refugees, this is on top of PTSD as a result of living in war zones.

A lot of migrants I work with experience depression and anxiety as a result of isolation, poverty, and segregation. We don’t really talk about racial segregation in Canada but it exists. One’s access to quality food, health care, education, and community centres depends on what neighbourhood you live in and whether it’s a rich white neighbourhood or not.

And I think these experiences of isolation and depression – as a result of systemic marginalization – are further compounded in immigrant/refugee communities due to stigma. There is already a general stigma to mental health issues, but for migrants I would argue it’s even greater because the migrant experience is inherently underwritten by the need to “be productive” and assimilate and prove that one fits in.

Ryan: So then if you are suffering from mental health issues or physical health issues there’s a real barrier to go and ask for help?

Harsha: Yes, there are barriers to seeking support especially because as a migrant you are meant to be productive in the capitalist economy. That’s often the explicit grounds on which people are allowed entry – for example as migrant workers or skilled workers. The migrant experience is so fundamentally tied into ideas of “being a good migrant,” and “a model migrant” which both historically and currently are intricately tied to performance in the wage economy. The very idea of belonging, as racialized migrants, is already so contested that admitting physical or mental health issues would be seen as diminishing what little worth one has.

Ryan: Even if you were born in this country, raised with a lot of exposure to the mainstream culture, there’s a sense that you still don’t belong.

Harsha: Yes, we see this a lot in first and second-generation Canadian kids. There is this constant feeling and experience of not fully “belonging” even though you were born and raised here. The very idea of who is really Canadian is racialized. One of the things I have been thinking and talk about is this experience of “constantly migrating.” In legal terms, a migrant is a newcomer and migration is a specific act, but given the realities of racism and exclusion and oppression, many communities are perceived (and often consider themselves) to be migrants, or hyphenated citizens, even after generations.

My partner was born in Canada, for example, and he had to go to English as a Second Language classes because they basically put all the Indigenous kids and all the racialized kids into ESL class. The accents or dialects that they carried from their home communities and their families were something that was frowned upon. So you’d have entire classes of brown kids, who were actually born and raised here, in ESL classes!

And that’s just a personal example, of course we have the more larger scale mobilizations of racism against communities of colour, for example in the post 9/11 climate against Muslims, Arabs, and South Asians who are Canadian but are cast as eternal outsiders.

Indigenous and immigrant alliances

Ryan: One of the things that you’re doing that I find interesting is that you are being really explicit when talking about the immigrant and refugee experience in making a connection to solidarity with Indigenous people. That’s tricky territory. I’d like to hear a little more about why you’ve chosen to make those connections and how you navigate them?

Harsha: That is at the heart of the work that I do day-to-day and what I care deeply about. I see how migrants of colour and Indigenous communities have been kept apart. There are a lot of misunderstandings and prejudices between communities. One obvious example is when newcomers are forced to read the guide to Canada before they take the citizenship test. The history is the very official state version that’s even worse than the public education system. It’s 30 pages on the War of 1812 and very little on the history of colonization. Migrant communities are fed all the racist narratives of Indigenous peoples, without being taught about the history of settler colonialism, and so become complicit within these systems and discourses and often reproduce them.

Similarly, within Canada in general and even more so amongst impoverished communities and Indigenous communities, there isn’t an understanding of what forces people to migrate. People often regurgitate the dominant racist frames of migrants “stealing jobs,” or that refugees are “terrorists” or “queue-jumpers” or “illegals,” when in reality most refugees are displaced peoples feeling persecution. Many are Indigenous to their home territories but have been forced off the land due to state occupation in the case of Palestinian refugees, for example, or all across Latin America, where people are being forced off of their lands because of Canadian mining companies.

So there’s a cycle where Canada is complicit in this global terrain of displacement. And displacement and dispossession of Indigenous peoples is of course what colonialism within Canada is based on. And so for me, talking between communities directly is central because I think our understanding of each other is mediated through Canada and the Canadian state and dominant discourses and not actually people’s lived experiences. In addition to that necessary dialogue, I think there’s also the added responsibility of how do we as migrants live responsibly on Turtle Island and how do we not become complicit in resettling and recolonizing.

Ryan: As I was preparing for this conversation, I kept thinking about a lyric from Shad, who’s going to be presenting with us next month in Vancouver. In his song “Fam Jam (Fe Sum Immigrins)” he says:

to the best restaurants, make reservations, since we out here, since they made reservations, for First Nations and they never made reparations, the natives probably relate more to immigration.

What do you think of that line, and the challenges in making alliances between Indigenous and immigrant populations?

Harsha: I think it’s complicated. I think we tend to believe that marginalized communities are natural allies in the struggle but we have to contend with the reality that colonialism has deliberately divided us and forced us to believe in narratives of each other that aren’t real. Canada is trying to assimilate Indigenous people within the Canadian state as well as to force migrants to assimilate within Canada. So you have communities that are forcibly being assimilated and everything is mediated through that lens. So I don’t think it’s a natural alliance because of the ways in which colonialism has disrupted that possibility and it requires a deliberate and intentional effort to bring communities together.

And also certain migrant communities of colour are used as wedges – so for example the model minority immigrant that “made it” is deliberately deployed against Indigenous communities, whom we are led to believe are individually “choosing” poverty rather than seeing poverty as a deliberate structure. So as migrant communities we have to be attuned to the ways in which we become complicit in colonialism.

Ryan: This is something I’ve been really interested in because a lot of people go there right away in health for the reason that a lot of the same determinants of health and access issues are common between Indigenous people and new arrivals. If you try to have a refugee and Indigenous clinic, maybe in some places it could work really well but there are barriers and problems to lumping those communities together.

What I hear from some Indigenous people in Saskatchewan is that immigration is at the heart of their problems: it’s just hundreds of years of immigration. I think that’s at the core; but there are other things around recognizing the unique cultural safety issues of working with Indigenous people that are different than people coming from a migrant background. I’m interested because you are really working hard to make those links and alliances and I’m wondering how you address those barriers?

Harsha: For me the key in making alliances is the inherent recognition that communities aren’t the same, all racialized communities have differential power and we definitely can’t homogenize experiences. Furthermore, the settler-colonial context is unique in terms of the racism being inherent to colonialism and Indigenous folks essentially being refugees in their own homeland. And so I don’t think communities should be forced on each other if it’s not desired because that can unwittingly reproduce settler colonialism.

I think it’s also important to be aware of how migration is increasingly state-managed. So we have some migrants – not a majority by any means, but some – who represent capital and are completely invested in the capitalist and settler-colonial project, for example investing in land grabs. This is a distinct racial and class-based context from displaced migrants, and these differences matter.

In the context of health there are some interesting things that have been happening in Vancouver. For example, alliances between non-status migrant people who can’t access healthcare and Indigenous people who refuse to register their children under the Indian Act. The informal health care networks of mutual aid that are developing to support these diverse communities are really interesting and inspirational.

Personal stories

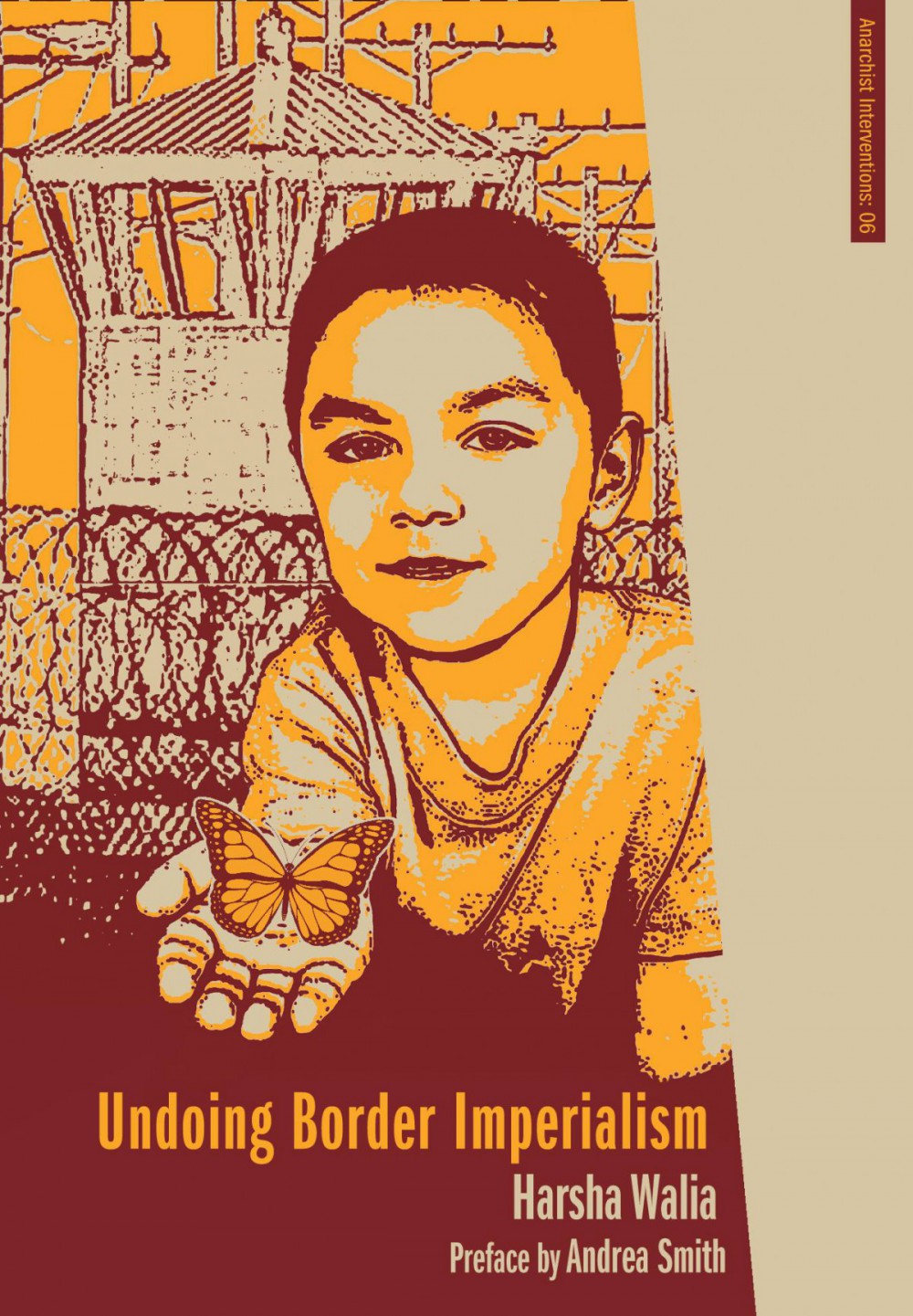

Ryan: One of the other areas I wanted to explore, after reading your book Undoing Border Imperialism, is that you have lots of neat vignettes and short stories. At Upstream we talk a lot about the importance of using personal stories to help illustrate a larger concept. Why is it important to you and your writing to have those stories at the heart of it?

Harsha: That’s all we are. We are made up of our stories and any kind of larger public dialogue is always informed by lived experiences. For me, storytelling is people speaking in their own voices. One thing that I think we’ve lost, especially with such a concentration of corporate media, is people being able to share their own experiences on their own terms. I don’t want to mediate people’s experiences; my goal is facilitating or providing a space for people to share their own stories.

Sometimes we have to talk in generalizations because we need to make a point. For example, when I’m talking about racism – it’s a general structure but it manifests in diverse ways and everyone has a unique experience with it. Going back and forth between the specific and the general really allows you to understand what’s happening.

The Trouble with Non-Profits and Single-Issue Campaigns

Ryan: How do you make the bridge between non-profits working on root cause issues to actually impacting the structures that create those issues, really changing what’s happening on a political level to make our work less necessary?

Harsha: I think in the left in English-speaking Canada, at least in the last 15 years, there has been a rapid decline of social movements. And I think in addition to external dynamics – like the rise of conservative forces, there is also a decline in the very idea of social movements. It’s not about romanticizing the street or protests, because social movements are involved at all levels. But social movements are not bureaucracies; they’re not charities, they’re not non-profits or NGO’s, they’re not institutions. What’s so necessary about social movements is not just that we need to have a root-cause analysis to structurally transform the systems we live in, but we also need social movements to foster our personal and collective sense of empowerment and purpose.

Social movements really rely on people as the primary agents of transformation. We see, for example, decreasing union density and union membership engagement while labour bureaucracies are growing. We cannot give up our own power to organizations; we need to understand ourselves as necessary and needed to make change possible. That is the power of social movements; they place the mirror back onto us to be self-determining.

Ryan: And the increased separation between social democratic parties, social movements, NGOs, and the labour movement. There’s lots of common goals, but they don’t want to talk to each other.

Harsha: I think single-issue campaigning has had an effect on that as well. You see that in the division between, for example, between environmentalists and working people. For example, a lot of Indigenous communities who live downstream from the tarsands are also working in the tarsands, often referring to themselves as economic hostages. And conversely, workers in the tarsands also care about the impact of the tarsands – workers are dying in the tarsands too. So it’s reductionist to assume that environmentalists don’t care about working people’s financial security and survival, or that working people don’t care about clean water.

Single-issue campaigning not only weakens us – by reducing the possibilities of alliance – it also portrays us as caricatures: you’re just a “tree-hugger” or you’re just a worker who only cares about money, as though we aren’t full people with a multitude of complex realities in our lives.

I went to the Indigenous-led Tar Sands Healing Walk a few years ago. It was a powerful event in so many ways, particularly witnessing the resilience of Indigenous communities standing up to this destruction. The one thing that I didn’t expect was that there quite a few buses of workers going by, and it seemed like buses of migrant workers, and they were all waving and cheering. And I wouldn’t have guessed that, because the predominant narrative is that workers in the tarsands love the tarsands.

A few years later in Calgary, a young student was describing how a number of her uncles and cousins were getting sick from working in the tarsands. She said, “We need the tarsands, but we don’t want them. I would rather my family not be getting sick.” The government and industry are invested in the tarsands, but the people in Alberta aren’t necessarily as sold on it as we think.

The polarizations between those who care about the land and those who are working in resource-extractive sectors mean we don’t build common cause. This is not to simplify or minimize very real tensions that exist, especially given the reality of ongoing settler colonialism, but I think single-issue campaigning reduces the ability to even imagine responsible alliances.

Ryan: Which is a great way of weakening any resistance or movement for change. If the people who have common cause think they’re on opposite sides.