What does it mean for Guantanamo Bay prisoners to assert their essential human dignity, and to seek justice, by choosing to starve? From freedom fighters under the British Raj to Chief Theresa Spence and the detainees of Guantanamo, physician Baijayanta Mukhopadhyay explores the insistent threat of the hunger strike.

Eventually, the body exhausts its riches. For a few days, it will find glucose, tucked away in the nooks of muscles, in the crannies of the liver, getting enough to get by, but sending worried, rumbling alarms to the brain. Then, it will adjust, reconcile itself to the fact that if there is not going to be food, food must be found. Over a few weeks, it will reluctantly dip into stores of fat it can burn, energy-rich savings that it worriedly watches dwindle. In response, the body’s systems decelerate, working to rule, threatening strike.

And then comes the cliff. Organs surreptitiously begin to mine the body, leaving gashes of desperation in their quarrying. Selfish and hungry, the heart and the brain scrabble most urgently, elbowing others out of the way. Muscles melt away as protein is shredded of nitrogen, unceremoniously discarded in the urine, leaving behind carbon-based molecules that cells rip apart for energy, all pretence of civility gone. Skin collapses, hair thins, bones weaken, cheeks hollow, eyes glaze, and hunger rules.

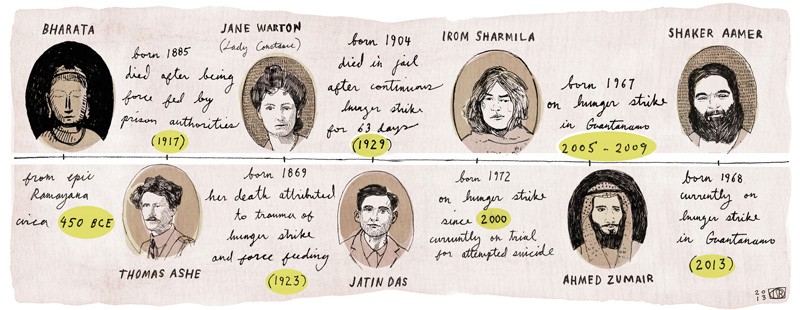

In Guantanamo, hunger has dominated daily life since 2005, when detainees like Ahmed Zuhair, a Saudi sheep merchant imprisoned without charge for seven years, started the first wave of hunger strikes. Now, over 100 detainees, consisting of more than half of those remaining at Guantanamo, are on hunger strike in protest of their indefinite detention. “I do not wish to die,” states an open letter signed by striking detainees in May, “but I am prepared to run the risk that I may end up doing so, because I am protesting the fact that I have been locked up for more than a decade, without a trial, subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment and denied access to justice.”

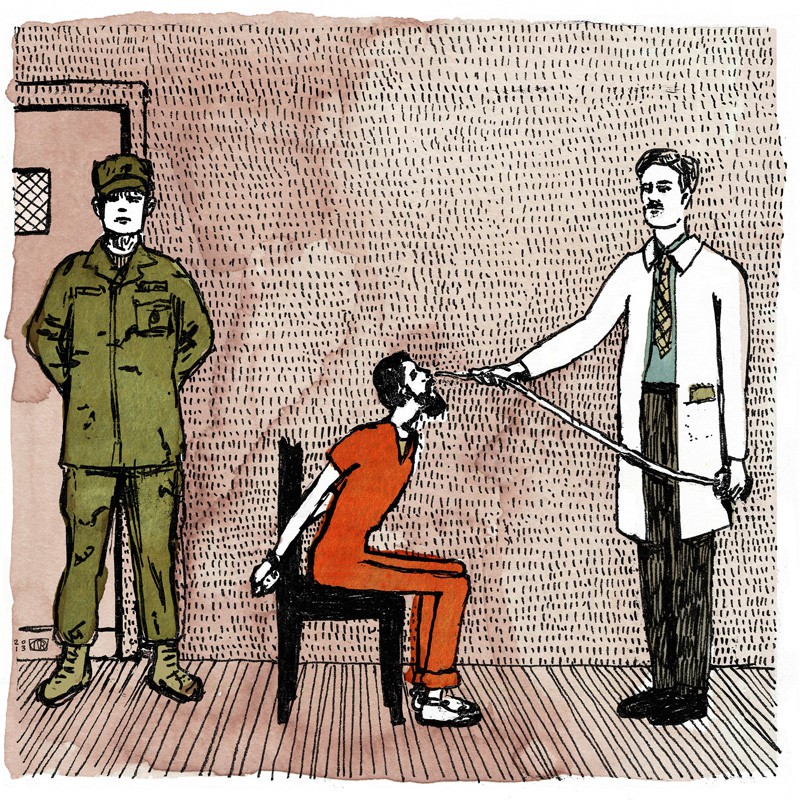

Journalists are barred from watching the force-feeding procedure in what Zuhair describes as a “torture chair,” in which detainees are restrained for hours at a time. A Forced Cell Extraction team is used to break the spirit of famished bodies refusing the procedure. “I wonder about America’s humanity,” Zuhair says, reflecting on the continued strike.

But hunger’s empire stretches far beyond America. For parts of the world where famine has left scars in collective memory, hunger carries symbolic weight that no one can dismiss. Those who deliberately take it on command attention.

One of the first documented uses of hunger as political protest goes back 2,500 years to the Indian epic Ramayana. Bharata, the noble half-brother of the hero, Rama, is unfairly appointed to the throne of the kingdom through machinations of his mother. The new king begs his sibling to return to reclaim the throne that is rightfully his, but Rama refuses as he promised their father he would accept the old king’s choice. Bharata threatens to fast until death in front of Rama’s forest dwelling unless he returns home to be made king.

Fasts continue to be a routine part of protest in India, and were used prominently in the independence movement. In 1929, Jatin Das died in a prison in Lahore after 63 days of fasting against the discriminatory treatment Indian prisoners faced compared to their British counterparts. His death at 24 became a seminal rallying point in the freedom struggle. And even today, far from the eyes of the world and, indeed, from many in India, Irom Sharmila continues a 13-year fast against India’s draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act that grants impunity to security forces for criminal acts. She started her strike in 2000 after she watched the Indian army gun down 10 civilians in the restive northeast of the country.

Famines an ocean away also shaped the Celtic tradition of hunger for the sake of justice. Richly referenced in Irish lore and ushered into the modern era with Yeats’ 1904 play The King’s Threshold, their historical culmination came with the hunger strikes of the early 20th century as Ireland fought for freedom from Britain, and, in 1981, led to the death of 10 Irish republican men in British prisons during the years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Hunger strikes work because, while power can attempt to control everything in an individual’s environment, it cannot control an individual’s will. We tolerate starvation when we perceive it as collateral damage of a stable social order, such as the chronic malnutrition caused by the contemporary global food system. But hunger that disrupts social order unsettles us. Hunger that deliberately resists authority to which we ourselves meekly submit reminds us of our own complicity. It is a discomfiting, visceral reminder of the damage that those who profit from power would prefer to remain invisible.

On this continent, where most of us do not comprehend its meaning, we are confused by hunger’s inclusion in the repertoire of protest. Oblivious to its symbolic significance, we respond to it in sharply divergent ways. Upon learning that Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence was drinking fish broth as part of her hunger strike last winter, National Post columnist Barbara Kay contended that it was “more like a detox ‘diet’ than a fast.” In lands accustomed to plenty, we have the luxury of laughing at hunger as a passing fad. Or, aware that the register of protest underneath it accuses us in some way, we suppress it with ferocity. The force-feeding of the hunger strikers in Guantanamo underlines this point: the more resistance threatens the dominant order, the more brutal its obliteration.

“… He has chosen death:

Refusing to eat or drink, that he may bring

Disgrace upon me; for there is a custom,

An old and foolish custom, that if a man

Be wronged, or think that he is wronged, and starve

Upon another’s threshold till he die,

The Common People, for all time to come,

Will raise a heavy cry against that threshold,

Even though it be the King’s.”

— The King’s Threshold, William Butler Yeats

Thirteen of the current hunger strikers at Guantanamo recently wrote an open letter to their military physicians, calling on them to cease force-feedings and hand over their medical care to truly independent practitioners. They do not mince any words regarding the physicians’ participation in breaking the strike: “You claim to be acting according to your duties as a physician to save my life. This is against my expressed wish. As you should know, I am competent to make my own decisions about medical treatment. When I try to refuse the treatments you offer, you force them upon me, sometimes violently. For those reasons, you are in violation of the ethics of your profession.”

Non-maleficence is the principle of medical ethics that reflects the popularly known Hippocratic approach of “first, do no harm,” or, at least, ensure the benefit outweighs the harm. But doctors must also consider principles such as beneficence, which compels practitioners to act in the best interests of the patient, and autonomy, the right of individuals to decide their own course of care.

Force-feeding contravenes these basic ethical principles, as recently affirmed by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health. The invasive nature of introducing tubes into a person, especially when done against their will, is risky in and of itself. Rapid refeeding after even a short period of starvation can be fatal within a matter of days, unless closely medically managed, as the body’s delicate chemical balance reels out of the careful equilibrium of scarcity. Force-feeding is considered to have caused the deaths of Mary Clarke and Jane Warton (Constance Lytton), suffragette hunger strikers in early 20th century Britain. Thomas Ashe, an Irish republican activist, died at the age of 32 after being force-fed in 1917 by British prison authorities. The ghastly crudity of the procedure seemed not to have changed in the intervening five decades before Michael Gaughan, another Irishman, died in 1974 after being force-fed while restrained by six to eight staff. The British government abandoned the policy of force-feeding hunger strikers after the controversy of his death, and the British Medical Association stated in 1984 that no diet that requires medical monitoring could be considered ethical.

The ethical principle most grievously wounded by force-feeding is that of autonomy, the freedom of every individual to choose their fate. Cases in Britain in 2012 showed that even where a mental illness prevents someone from consuming the calories necessary to sustain life, such as in anorexia nervosa, courts often quavered when granting physicians the right to interfere in the dignity of choice for a person who understands the consequences of their actions. In its invasive intimacy, force-feeding renders people powerless in a cruelly calculated and undignified way.

Medicine is supreme in forcing people to surrender control of their bodies to mystical powers unknown, but it is done more politely at everyday hospitals than at Guantanamo, which has a logic comprehensible only to itself. Shaker Aamer, considered by many to be the unofficial spokesperson of the Guantanamo detainees, wrote in March 2013: “American prisons try to control you by taking away every choice you might have, as that’s what we humans use to build our sense of who we are, whether it’s something trivial like what we have for dinner, or something important. They try to reduce you to nothingness … I have been deprived of everything but my life. So that’s the only decision I have left: to live or to die.”

But why pretend that medical ethics govern the situation in Guantanamo at all? Force-feeding hunger strikers is not a medical act; it is a political one. As is clear from the Joint Task Force military documents released by Al Jazeera in May outlining the force-feeding protocol, it is the military commander at Guantanamo, not a physician, who has final authority on who gets force-fed. The intent is not to appease suffering or to treat an illness. There is no doctor-patient relationship in Guantanamo, simply – as in British prisons in India and Ireland before it – a relationship between jailer and prisoner. American military physicians are servants of their masters in government – somewhat ironic in a country given to spasms of horror at the prospect of government involvement in health care.

The World Medical Association’s 1975 Declaration of Tokyo expressly forbids the force-feeding of hunger strikers who are deemed competent, “capable of forming an unimpaired and rational judgment concerning the consequences of such a voluntary refusal of nourishment.” It stresses that this assessment must be validated by another independent physician. The more nuanced Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikers in 1991 by the same organization directly addresses many of the concerns a physician working in such environments might have, providing strategies to guide a physician through solving ethical dilemmas. Most critically, the Declaration of Malta states that “If a physician is unable for reasons of conscience to abide by a hunger striker’s refusal of treatment or artificial feeding, the physician should make this clear at the outset and refer the hunger striker to another physician who is willing to abide by the hunger striker’s refusal.” It also draws a line between artificial feeding, to which a striker may consent, and forced feeding, which “is never ethically acceptable. Even if intended to benefit, feeding accompanied by threats, coercion, force or use of physical restraints is a form of inhuman and degrading treatment.”

Both medicine and the military are deeply hierarchical structures, practitioners of each trained from the outset to follow orders from above. But in medicine, the top of that pyramid should be the patient. Medical practitioners at Guantanamo are not treating patients, but appeasing the rage of those aware that absolute power is slipping away from them. Wasting bodies, the odour of decaying muscle on the breath of prisoners, the glint of stubborn pride in eyes otherwise fading with fatigue, the contagion of resistance no matter how many solitary cells are used – these are all signs of a festering revolution that tubes and shackles, anger and liquid diets will not suppress. Guantanamo doctors try to treat resistance as disease, to pathologize protest. But there will be no cure.