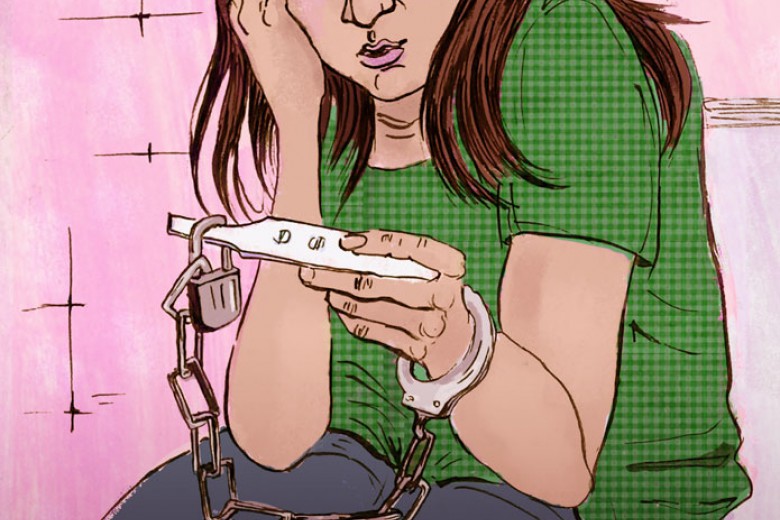

On January 7, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association filed a lawsuit against the Higgs government in New Brunswick, challenging the constitutionality of the province’s restrictions to publicly-insured abortion services. Section 2.a.1 of Regulation 84-20 of the N.B. Medical Services Payment Act, enacted in 1984, states that abortion is “deemed not to be entitled services” for provincial payment unless it is provided in an approved hospital facility. Other services similarly banned from public payment include cosmetic surgery and breast augmentation. The regulation effectively excludes abortion care provided by Clinic 554, the former Morgentaler Clinic in Fredericton, from public coverage. The federal government has reprimanded New Brunswick for being the only province in the country that refuses to fund clinic-based abortion, a move that violates the Canada Health Act.

As a registered nurse working in abortion care and research, I recognize there are many potential advantages to going to a clinic for abortion care, such as a welcoming environment; more specialized staff; and reduced travel time, since many clinics also provide related services like ultrasounds and bloodwork collection. But in New Brunswick there are two additional, critical benefits. First, Clinic 554 is the only provider of aspiration (surgical) abortion in Fredericton – the other aspiration abortion sites are hours away in hospitals in Moncton and Bathurst. Second, Clinic 554 provides abortions up to 16 weeks, while the hospital services stop at 14. With barriers to care including stigma, transportation, COVID-19 restrictions, and a severe shortage of primary care providers, those two weeks can make a serious difference in access.

I recognize there are many potential advantages to going to a clinic for abortion care, such as a welcoming environment, more specialized staff, and reduced travel time.

In 2004 Dr. Henry Morgentaler pursued a legal challenge against New Brunswick over its distinctive restrictions on abortion payment. After protracted opposition by the province, the court granted him “standing” in 2009, recognizing that although Morgentaler, a cisgender man, was not a patient who experienced discrimination or harm due to the restrictions, there was a public interest argument to allow him to bring forward the case: there are personal and financial costs to legal action that make it rarely viable for individual patients. At the time Morgentaler was challenging N.B., I was a volunteer at his clinic and fundraised for his legal campaign. He died in 2013 before the lawsuit could be successful.

Immense efforts by feminist activists – such as the 1970 Abortion Caravan, the 1970’s Calgary Birth Control Association referral service for abortion patients to providers in the U.S., and the 1982 formation of the Ontario Coalition for Abortion Clinics – successfully shifted the public attitude toward supporting reproductive rights in Canada. But it has largely been legal battles that cemented permanent change. The 1988 Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Morgentaler resulted in the complete decriminalization of abortion in this country. It expanded legal access in a way that is, internationally, nearly unparalleled. Although over 60 countries permit abortion on demand, most have limitations such as caps on how far along the pregnancy can be.

Abortion in Canada is outside of criminal law. The Supreme Court found that criminal code restrictions on abortion violated Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the right to security of the person. In 1993, Morgentaler won a legal dispute with Nova Scotia over harsh fines the province imposed on his Halifax clinic. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that through the fines the province had created an invalid criminal law, as criminal law is under federal jurisdiction. In 2016, Abortion Access Now Prince Edward Island (cleverly abbreviated to AANPEI), with the support of the Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund and represented by Nijhawan McMillan Barristers, filed a suit against that province’s 30-year “ban” on abortion service provision on-Island. AANPEI won before the case even went to court, and PEI launched comprehensive abortion services the next year. These legal battles fortify the access we experience today.

The cost of maintaining the abortion service without public remuneration – including a procedure and recovery room, and social work and nursing staff – proved unsustainable.

The CCLA lawsuit is a long-overdue and last-ditch attempt to save Clinic 554. For five years, until last fall, the clinic operated as a general family practice, with both abortion and services for transgender people integrated into care. All the care except aspiration abortion was billed to the province. The cost of maintaining the abortion service without public remuneration – including a procedure and recovery room, and social work and nursing staff – proved unsustainable. Dr. Adrian Edgar, the physician who took on ownership and operation of Clinic 554 after Morgentaler’s death, was forced to shutter his family practice in October 2020, leaving thousands of patients without primary care. This was also a severe blow to the LGBTQ2S+ community.

Decriminalization, Medicare coverage, self-referral and primary care access to medical abortion make Canada an international leader in access to abortion. The physical size of our country and a shortage of trained and willing providers remain persistent challenges, but telemedicine and improvements to education are making headway to resolve these issues. The exclusion of clinic-based care in New Brunswick is inconsistent with regulations and care provision in the rest of the country. It is discriminatory, partisan, and simply harmful to health. Pursuing a defense against CCLA’s suit will cost New Brunswick taxpayers unnecessarily, and likely unsuccessfully. Regulation 2.a.1 of 84-20 indefensibly infringes on the rights of people who can get pregnant. A vote in the legislature is not required to change the regulation, all that is required is a decision from the Premier’s cabinet. We have a very difficult road ahead of us for health in 2021; may this no longer stand in the way of equity and care.