In 1970, 35 women chained themselves to the parliamentary gallery in Ottawa as part of a mass demonstration for abortion rights. With R. vs. Morgentaler in 1988, the Supreme Court struck down the section of the Criminal Code regulating abortion, finding that it violated section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Today abortion is a safe, legal, and common medical procedure, but in the Maritimes and in northern and rural communities across Canada, there are major barriers to access.

A few years ago a young woman was travelling alone from a Halifax hospital where she had just had an abortion to her home on Prince Edward Island. “I took a plastic bag to sit with me on the shuttle,” she later told a university researcher. “You can’t ask the driver to pull over.” During the five-hour bus ride, she bled through multiple hospital pads and then onto the bag. A young mother of two leaving an abusive relationship, she couldn’t afford to travel to Halifax early in her pregnancy, and social services refused to pay for anyone to accompany her. By the time she received funds to travel, her pregnancy had progressed considerably, increasing the risks of the abortion. After she got home, she learned her cervix had been nicked during the procedure, but social services wouldn’t pay for a second trip to Halifax for her treatment.

“My research shows that lots and lots of women faced horrendous discrimination and violation of their human rights,” says Dr. Colleen MacQuarrie, the University of Prince Edward Island psychology professor who spoke with the young woman, “but she really stands out as somebody the system failed again and again and again.”

Prince Edward Island is the only province or territory without a single abortion provider, but for many Canadians living far from large urban centres, accessing abortion is a process riddled with challenges, beginning with access to information. Although the P.E.I. government has paid for women’s abortions in Halifax since 1995, they didn’t publicize that fact for years. “Instead [the policy] was just quietly and discreetly communicated, apparently to the physicians, but no one else was told,” says MacQuarrie. The government only put information about abortion access on their website in 2011 after pressure from activist groups. Throughout Canada, it can still be difficult to find accurate information.

“Out in Boharm”

“Our Women’s Health Centre in Regina has a phone number … and she’ll get info right away about what’s available and what steps she has to take to access the service,” says Dr. Sally Mahood, a family physician and abortion provider in Regina. However, “you’ll have to know that it’s legal in Canada and there’s a hospital in Regina with a women’s health centre and there’s a phone number in the phone book. And if you’re a 16-year-old in Grade 10 out in Boharm, you might not know that.” Young or disadvantaged people may also have trouble confidentially accessing the Internet – they might not want to research nearby abortion clinics in their living room or at the library. In the territories, where few telecommunications companies operate, Internet access is expensive, says Susan Manning, a researcher at the Feminist Northern Network (FemNorthNet). She adds that recent immigrants who don’t speak official or Indigenous languages also face additional barriers. Asking a family doctor for a referral might be helpful, but not all health-care professionals are informed or willing to comply. In a 2006 study authored by Jessica Shaw for Canadians for Choice, researchers made calls to hospitals across Canada pretending to be a 20-year-old woman looking for a first-trimester abortion. The report revealed that a few hospital workers in Manitoba and New Brunswick referred callers to anti-abortion organizations, and 75 per cent of staff members who answered the phone at Alberta hospitals didn’t know if their hospital offered the service.

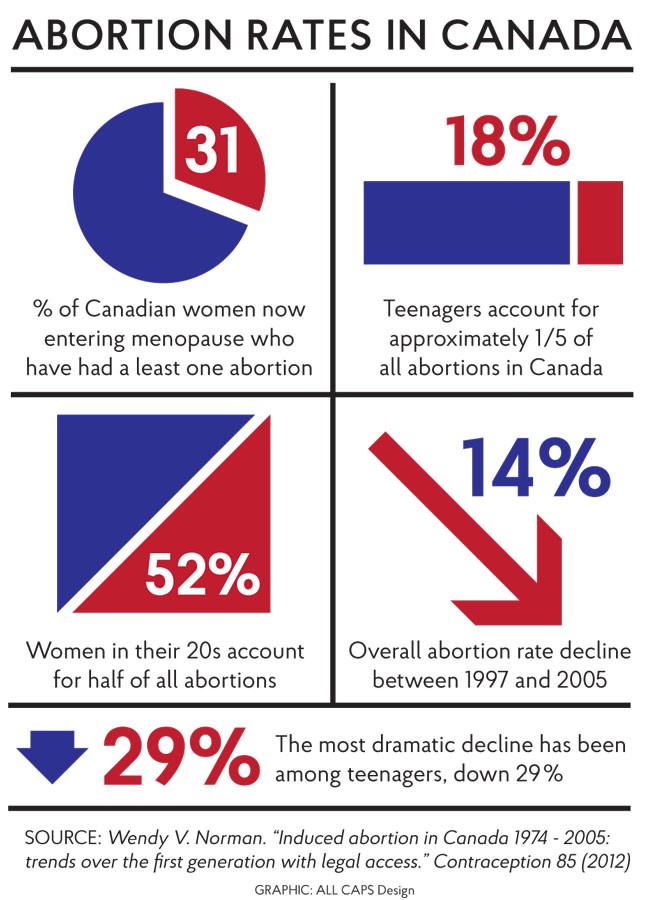

Even more worrying is the fact that some medical schools don’t properly teach about abortion. “We had one one-hour pharmacology lecture on birth control,” says Caitlin Hunter, a second-year medical student at the University of Saskatchewan, “and there were two slides on abortion, and there were not many specifics given about it.” As co-chair of the school’s Reproductive Action Group, Hunter has learned a lot about abortion through independent research, but medical schools can’t depend on all students taking such initiative. Since 31 per cent of Canadian women now entering menopause have had an abortion and 38 per cent of Canadian medical students list family medicine as their first choice of discipline, medical students “need to know the difference between a medical and surgical abortion, when each is done [and] at the very least know who to refer to if you’re unwilling to do it yourself,” says Hunter.

During medical abortions, patients who are six to nine weeks pregnant take oral medication, and during surgical abortions, doctors remove pregnancy tissue from the uterus with a suction tube. Some women prefer medical abortions because they seem more like miscarriages, says Dr. Christabelle Sethna, a University of Ottawa professor who researches abortion access in Canada with UBC post-doctoral fellow Marion Doull.

In some cases, however, even family physicians play a role in reinforcing stigma and impeding abortion access. When one woman asked her family doctor for a referral, Shaw’s study reported, the doctor “pretended to listen to the heartbeat of her ‘unborn child’ and in rhythm with the beat he said, ‘I love you mommy … I love you mommy.’”

Ontario and Saskatchewan’s regulatory colleges have drafted policies requiring physicians who won’t provide services on religious grounds to refer patients to a colleague. Some hope this will curb pro-life doctors who, Mahood says, have “told patients they weren’t as pregnant as they were to delay them.” Religious groups in Ontario are opposing these policies with a charter challenge.

Of course, the problem of stigma does not begin and end in the doctor’s office. It is shaped by a society that “continues to uphold motherhood as the sort of major benefit and sign of womanhood,” says Sethna. One project that aims to decrease broader stigma around abortion is One Kind Word, a book of portraits and stories of Canadian women who have had abortions. “Showing women’s faces that are just like you and me, and telling women’s stories that could have been my story, could be your story, it’s really about that,” says Kathryn Palmateer, the project’s photographer. Her grandmother “had never told anybody about [her abortion]” and “suddenly, she felt like she could be open about it when she was starting to hear stories of other women.”

But let’s say a woman overcomes all these barriers regarding stigma and access to information. If she lives in Kuujjuaq, QC or Grise Fiord, NU, or even Fredericton, N.B., it can be a challenge to access the procedure itself.

“Last week I saw somebody from Pinehouse, which is about as far north as you can go in Saskatchewan,” says Mahood. Only hospitals in Regina and Saskatoon offer abortion, “so this woman had to drive six to eight hours to have a five-minute procedure.” The Women’s Health Centre provides telephone counselling for long-distance patients, but they eventually have to travel to Regina for the procedure itself. And that means finding child care, arranging for time off work, paying for gas or bus tickets, perhaps coming up with an excuse for their time away, and doing it all alone if a friend, relative, or partner can’t afford to travel with them. Mahood also points out that due to hospital wait times and delays due to finances, rural women are often too far along in their pregnancies to access medical abortion. Later-term abortions increase the risk of complications, such as the cervical nick suffered by the woman from P.E.I. “That’s why impediments like enforced wait times or repeated appointments … impede access through stealth,” says Sethna.

Bernadette Wagner, who travelled from Regina to Saskatoon for an abortion in 1985, had to wait months to get an appointment. Before 1988, Canadians wanting to terminate a pregnancy needed approval from a therapeutic abortion committee. No Regina physician would take Wagner’s case to the committee, so she travelled to Saskatoon where she had heard a doctor would provide abortions if patients could prove local residency. She used a friend’s Saskatoon address and lied about being a student there. “I can still see myself sitting there with the intake worker,” says Wagner. “I could just feel myself shaking inside as I gave my address … I was just waiting for them to say ‘well, no.’”

Crowdfunding a clinic

Thirty years later and a few thousand kilometres to the east, women in Atlantic Canada continue to face challenges when trying to access abortion services. When Fredericton’s private Morgentaler clinic closed in July 2014, New Brunswick women had to travel to one of two hospitals in the province that performed first-trimester abortions, while Prince Edward Island women had to travel to the Halifax hospital. Wait times in both provinces increased and the Mabel Wadsworth Women’s Health Center in Maine, a three-hour drive from Fredericton, saw an increase in Canadian patients. “It was very noticeable when [Canadians] became half of the women here, instead of one every six or seven months,” says Ruth Lockhart, the clinic’s executive director.

But Lockhart has noticed fewer Maritimers at her health centre since January, when Clinic 554, a family practice that also offers abortion services, opened in the old Morgentaler space. Activist groups Reproductive Justice New Brunswick (RJNB) and Fredericton Youth Feminists raised over $125,000 on Kickstarter “to help purchase the building so that a family practice could be opened, with the understanding that [it] would also perform abortions,” says Jessi Taylor, a spokesperson for RJNB. Donors were primarily New Brunswickers, some of whom would pass along “envelopes with notes saying, ‘this is everything I can give,’ and it would be five dollars.”

But even with Clinic 554 open, many New Brunswickers still struggle to access abortions. For years, the provincial government only paid for first-trimester abortions at the Moncton and Bathurst hospitals in the French-language hospital network; patients also still need a doctor’s referral for those hospitals, and procedures at all clinics cost around $750. Waiting times for hospital abortions can be as long as six weeks, says Taylor, which leaves some women too far along in their pregnancy to access government-funded options. In April, a Moncton hospital in the English-language hospital network began providing abortions, but Taylor says, “it’s a little bit of a slap in the face” since many other areas of New Brunswick still have no access to services.

Government-funded clinic abortions, says Taylor, would be most beneficial in terms of both cost and patient experience. This is the Quebec model: each of the province’s 17 administrative districts has at least one first-trimester abortion clinic, explains Patricia LaRue, director of the Clinique des femmes de l’Outaouais in Gatineau. Community health centres in Montreal, Quebec City, and Sherbrooke offer second-trimester abortions, and the Montreal clinic also handles referrals to the United States for later-term procedures. “There’s a political will to make it work,” says LaRue.

Nonetheless, women living in remote areas can still have difficulty reaching services. The Nord-du-Québec region is vast, and abortion services are only provided in one community, “so you have people in Kuujjuaq who would need to travel [989 km] to Chibougamau to get access to services,” says LaRue. The provincial government covers transportation when women need to travel more than 300 km.

Concerns have also been raised about Bill 20, which the Quebec Liberals introduced in May 2014. If passed, there are concerns it would limit the number of abortions family doctors can provide, and would delist abortion as “a priority medical activity.” Health Minister Gaétan Barrette stresses that these new rules would only apply to new physicians, but medical groups and other political parties fear Bill 20 will reduce access to services.

For women across Canada, the Norma Scarborough Emergency Fund can provide financial assistance. “It’s a small fund and we try to coordinate with other, similar funds that provide support, such as the one operated by the National Abortion Federation,” says Sandeep Prasad, executive director of Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights, which administers the fund. “It really amounts to a portion of some of the costs associated with actually travelling to obtain the procedure, whatever that might look like. So that could be a bus ticket, that could be a night at a hotel.” Women also look to their own networks for financial support. “Typically, what happens when a woman contacts me is I just let the [P.E.I. Abortion Rights Network] know and we sort of cobble together resources,” says MacQuarrie.

In Nunavut, few women face economic barriers to accessing abortions, which are provided in Iqaluit during the first trimester. “You’d expect Nunavut, we’re far from urban centres, we should have terrible access issues,” says a Nunavut physician. But if you are Inuk, all costs are covered. “Even if they live in Grise Fiord, which is an $8,000 flight from there to Iqaluit, or even if they’re 19 weeks and they need to go down to Ottawa or Toronto, it’s completely paid for, completely organized, even meals, even driving to the appointments,” she says. Non-Inuit women who need to travel south for any health reason have a copayment fee of $250, but that doesn’t include accommodation or meal expenses.

The physician estimates doctors in Iqaluit perform 80 to 100 abortions each year. Even if the Nunavut abortion rate is lower than the overall Canadian rate, she says it’s not a result of systemic barriers to access. “It’s that it is normative to have five babies here … it’s rarely stigmatized to be a teenager and have a kid,” she says. Adoption is also “normative [and] celebrated,” and she estimates one in six babies she delivers is adopted by another family.

Some Nunavut women who consider abortion are discouraged by the need to travel to Iqaluit or the South alone, since the government doesn’t cover a companion’s travel expenses for adults. Moreover, as in the rest of Canada, women are still responsible for child-care costs and for arranging for time off work. “For some people, that is too much,” says the physician, and they’d prefer to remain pregnant in their own community.

The road forward

Women shouldn’t be cobbling together resources to access a safe, legal, and common medical procedure. Depending on the region, governments need to either fund more remote clinics, as in Quebec, or fund travel, as in Nunavut. Another way to improve access would be for Health Canada to approve mifepristone, an abortifacient that has been used in France, for example, since 1988. Currently, the drugs used for medical abortions in Canada are effective up to six weeks’ gestation; with mifepristone, medical abortions can be performed until nine weeks. Mahood hopes mifepristone “would just be something that family doctors could offer in their offices,” which would allow more women to avoid travelling for abortion.

In 2013, California passed a bill allowing specially trained nurses, midwives, and physician assistants to perform first-trimester abortions. A study published in the American Journal of Public Health found the non-physicians completed procedures with complication rates almost identical to those of doctors.

While these are important steps, training nurses to perform abortions and legalizing mifepristone aren’t enough to make abortion accessible to chronically underserved rural women. MacQuarrie stresses that surgical abortions must also be available in case mifepristone doesn’t work, and the Nunavut physician points out that most communities in the territory wouldn’t benefit from non-physicians being able to perform abortions “because they can’t get a quantitative data ECG done on-site and they can’t get an ultrasound.” In other words, it’s a matter of equipment, not personnel.

Canadian residents must continue organizing and lobbying their provincial, territorial, and federal governments to ensure every woman can access abortion, like every other essential medical procedure. Let’s work to legalize mifepristone, fund more clinics in remote locations, and provide more dignified and comfortable transit to and from urban centres. Transit rides can be long and bumpy, but this is a campaign bus we need to drive.

Andrea Walker Memorial Article 2015

The Andrea Walker Memorial Fund was established in 1986 to commemorate the life of Andrea Lea Walker, a former Briarpatch staff person and a well-known and much-loved activist who died from cancer at the age of 33. The fund was established to assist writers and artists who address women’s health issues from a feminist perspective. This year’s grant – awarded to journalist Sara Tatelman for her article on abortion access in this issue – has been supplemented by a donation from CUPE Saskatchewan.