“We’re not just losing farms, we’re literally stabbing a stake in the heart of the most productive farmland in the country,” says Kevin Thomason, an advocate for Fight for Farmland, a group resisting a large-scale agricultural expropriation in the Township of Wilmot.

In March 2024, owners of six farmland properties and six residential homes in Wilmot Township received knocks on their doors. Canacre, a consulting firm with offices in the U.S. and Canada, handed them an ultimatum: either sell their farmland for $35,000 an acre or be expropriated. They were given ten days to decide. These knocks sparked over a year and counting of protest and strife within this rural community, extending far beyond Wilmot and raising questions often left unasked about rural solidarity and agricultural advocacy across Canada.

Wilmot is a small rural township bordering Waterloo Region in southern Ontario. It relies on agriculture and trucking as its two major industries. Like many other rural townships across Canada, everyone knows everyone, and most families have been in the region for generations, including the farmers threatened with this expropriation. It is classified as Class 1 or prime farmland under Canada’s designation system, the top class of farmland available and which only covers 0.5 per cent of Canada’s soil – however, this statistic has been circulating since the late 1970s and with the decline in farmland in Canada and a lack of updated information, it’s unclear whether this number has stayed the same. This is the only farmland able to grow vegetables with minimal limitations, making it essential for Canada’s food sovereignty. The impacted farmers grow cabbage alongside many other vegetables and produce cheese from the dairy farms both on and surrounding the outlined land for expropriation.

Rural agricultural expropriation takes on a special character; not only are these homes, these are livelihoods and long regional legacies.

Wilmot also lacks extensive infrastructure. The entire township’s drinking water runs on a waterline through the Waterloo aquifer. The vast majority of the township’s roads are older tar and chip rather than asphalt, with many being gravel and unsuitable for heavy industrial traffic. There are only a handful of small public schools scattered across the township, and there is a single van running on weekdays that serves as the only bus source in town, running from the grocery store at the edge of New Hamburg to the borders of the closest urban area, Kitchener. Housing and social services in the area are already under immense strain. This past year, Wilmot citizens spoke out against a proposed property tax hike of 51 per cent due to the township’s ongoing financial crisis.

This is not a township that can handle the strain of a large-scale industrial site but the regional and provincial leadership thinks industrial development is one way out of the crisis and has deemed it too weak to fight back.

Fight for farmland

Upon receiving Canacre’s notices on behalf of the Region of Waterloo and Wilmot Township – and funded by the provincial government – the landowners immediately contacted each other. They went together to the township offices to ask for an explanation but were met with silence – the township councillors were bound by non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), requiring them to not reveal the purpose of the expropriation. The landowners went further, to the regional Waterloo government, only to find that they too had signed NDAs. Residents and farmers were set to lose their homes and livelihoods and nobody would tell them why.

Fight for Farmland formed here. All those who had received knocks and threats of expropriation collectively refused the offer to sell.

Rural agricultural expropriation takes on a special character; not only are these homes, these are livelihoods and long regional legacies. Expropriation involves uprooting entire family histories and lifelong, if not generational, careers. “They are basically threatening to take my life away from me” says impacted farmer Stewart Snyder.

Members of Fight for Farmland attend the 105th International Plowing Match, filling the seats to protest the expropriation of farmland in Wilmot at a speech given by Ontario premier Doug Ford. Photos by Fight for Farmland.

United and backed by hundreds of community members, the farmers and residents began advocating together against the threatened expropriation of their combined total of 770 acres of land. They organized protests at every council meeting, tractor convoys to Kitchener, Ontario slowing traffic to the city for up to six hours, a mini-documentary series, and letter and phone campaigns.

Supporters filled the seats at the most recent International Plowing Match, flooding the audience for Premier Doug Ford’s speech with shirt after shirt declaring “NOT WILLING HOSTS” for the unspecified industrial site. Twenty-one times, they have had their requests for information almost entirely denied by the regional government – and the province has enforced the region’s NDA, even as Ontario premier Ford claims to be confused by the lack of transparency.

“We're not getting tired. I think they’re trying to tie us up and that's not happening,” says Eva Wagler, neighbour and supporter of the farmers facing expropriation.

With every farm that is lost, local food systems weaken. As more of the population is distanced from farming and an understanding of how crops are grown and livestock is raised, agricultural sovereignty is increasingly threatened.

To this day, no one knows how the land would be used if expropriated. Theories of a Toyota plant or an electric vehicle battery factory have been floated and dismissed again and again.

One piece of the puzzle

This opaqueness should, and does, concern many in the area, as the expropriation continues. Importantly, the Ontario chapter of the National Farmers Union issued a statement in solidarity with Fight for Farmland and has been regularly compiling information to facilitate access for those looking to keep accurately informed on this case. Other organizations such as Citizens for Safe Ground Water, the Ontario Federation of Agriculture, and the Waterloo Federation of Agriculture have also issued solidarity statements, standing with Wilmot farmers in this fight against expropriation. Their solidarity not only supports those whose land is at risk of expropriation, but it sets a precedent for other cases that may follow.

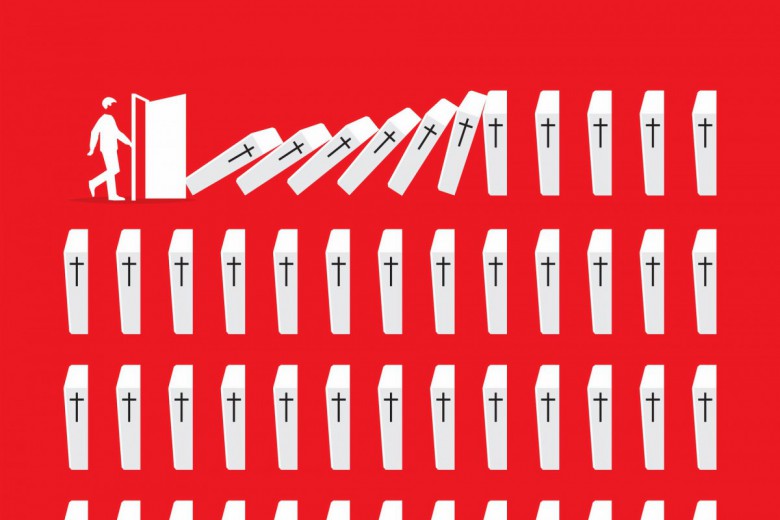

This is because Wilmot is part of a much wider, longer trend of food sovereignty coming under threat within Ontario and across Canada. In the province, as of 2020, urban sprawl (which has faced dramatic upticks throughout Ford’s premiership) lead to an average of 319 acres of productive farmland being lost every day, the equivalent of one family farm. The province of Ontario has a diverse range of soils due to the geography of the province, yet at this rate all of Ontario’s farmland is set to be lost within the next 100 years. This is a creeping but significant loss to the provincial economy, as the agricultural sector supports roughly 11 per cent of the provincial workforce and contributes more than $50 billion annually in economic activity.

With every farm that is lost, local food systems weaken. As more of the population is distanced from farming and an understanding of how crops are grown and livestock is raised, agricultural sovereignty is increasingly threatened. Food chain issues during initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed an overreliance on broad global food networks and amid our national affordability crisis, rising grocery store prices serve as a reminder of just how inaccessible fresh and affordable food is becoming. Local food networks are essential for the reliable food systems we need to sustain us.

Wilmot is a clear case study within a much larger, much broader erosion of local food networks to make room for large industrial operations. Member of provincial parliament Catherine Fife calls the Wilmot land expropriation "this government's next Greenbelt scandal. Wilmot has become ground zero for farmers across this province.”

Although there are regional differences, many farmers and municipalities across Canada are facing similar challenges. Quebec and British Columbia are also facing immense pressures of urban sprawl eating into farmland, along with infrastructure projects depleting the capacity for food production. Nova Scotia is dealing with sprawl on top of losses of essential agricultural support services such as food processing facilities and vet clinics. Succession planning, land affordability, and barriers to entry for the upcoming generation of farmers are impacting farmers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and increasing severe weather events, disasters, and wildfires across Canada are now annually damaging farms and critical transportation infrastructure, frequently wiping out entire crops and orchards.

Wilmot Township should concern agricultural areas across the country. If this can happen on Class 1 farmland, this same action can easily happen in other regions – on differently classed farmland, in more remote areas, with less public support. This level of land expropriation has only been possible through Premier Ford’s early 2024 enactment of Bill 162 (the Get It Done Act), which expedited expropriation and the need for public input. Wilmot’s land expropriation is neither an inevitability nor an age-old and unsolvable problem. It has been enabled by legislative changes occurring within the last few years under the current premier, but these can be resisted and changed. This should serve as a cause for solidarity from farmers in other areas of Canada seeing similar trends occurring in their regions.

Stumbling but Not Falling

Last July, one of the landowners broke and sold their land to the Region of Waterloo. In what farmers are calling an act of “brutal destruction,” the region quickly hired a company to plow the cornfield upon the transfer being made, destroying 2.8 million pounds of corn across 160 acres, a massive financial loss at roughly $160,000. The crop was just weeks away from harvesting. The Waterloo Region Record reported, “For a community that is all about caring for the land and cultivating crops, it was seen as an act of aggression and intimidation, said Alfred Lowrick, a spokesperson for Fight for Farmland.” No apology from the region has followed, and demands from community members for an inquiry only resulted in a report that was sparse at best and made flawed claims.

This is the solidarity that the Region of Waterloo cannot fully grasp – a solidarity that gets increasingly expensive for them if more and more companies refuse to help steal land from their friends and neighbours.

The plowing incident has faded into the background for Fight for Farmland supporters as questions around international tariffs, provincial and federal elections in both Canada and the U.S., and new municipal issues continue to change the discursive landscape. Since then, more of the 770 acres has been purchased by the Region of Waterloo in preparation for development.

However, this incident should not be so easily dismissed or forgotten. Its tragedy also highlights a key component of the fight within Wilmot and one that the Region of Waterloo finds difficult to anticipate and quantify – the solidarity and collaboration of farmers and residents. The company hired to do this sudden plowing had to be sourced from over 100 kilometres away in Strathroy as farmers in closer proximity had refused on principle.

This is the solidarity that the Region of Waterloo cannot fully grasp – a solidarity that gets increasingly expensive for them if more and more companies refuse to help steal land from their friends and neighbours. Wilmot Township is an area with a strong history of protest and a strong identity as a proud farming town. It is in this same area, and in the same rural southern Ontarian spirit, that community members lined up their plastic lawn chairs in front of entrances to proposed gravel pit sites known to contaminate local air and water, forming an effective blockade that resembles and functions as yet another porch social.

And they will do just the same for this fight.

Protests have not slowed or dwindled over time – Wilmot’s community members remain steadfast in their commitment to protect and fight for each other. To prey on people who make a modest living off their land year after year, lacking the formal degrees, suits and ties, or deep connections to politicians in the region may appear to be simple – but these are the people that Wilmot respects the most, and in this struggle, they have become emblematic of the township’s character. (Throughout my childhood in Wilmot I knew I was close to home whenever we passed a rusted-out billboard on the edge of town that read “Don’t Bitch About Farmers With Your Mouth Full.”) I have been seated in town halls that have devolved, as they often do, into bickering and yelling and tears as participants grapple for time at the microphone, shouting over councillors and township staff, and I have witnessed everyone fall silent when one of the impacted farmers stands up to speak, watching people move aside from the microphone to prioritize and centre their voices.

This does not just stop at Wilmot, however. This ongoing land expropriation case should worry areas far and wide. Wilmot’s case is a clear, documented example of undemocratic governance and exploitation of rural community members. These community members are also exercising all their civic avenues to democratically oppose this action by various levels of government.

Efforts to oppose the expropriation show that communities are watching and willing to support impacted farmers. Like those who refused to plow their neighbours’ fields, these networks are strong and are only bolstered in the face of this expropriation battle. In the context of an ongoing Ford premiership, alongside other premiers similarly interested in furthering the exploitation of farmland and those living on it, Wilmot’s land expropriation is a litmus test. If industrial development proponents can win here, they gain a valuable precedent to win elsewhere, continuing this trend of undemocratic and exploitative land expropriation. This is a well-publicized case, with plenty of ongoing well-organized and high-energy public support, yet the farmers still have not gained access to crucial information and the case continues to be stalled.

There is no end in sight. However, farmers continue to protest, and community members remain on standby to react to whatever development will occur next. But they do so in solidarity with each other, prepared to do all that is in their power to stop this expropriation from occurring.

And as Wilmot farmer Arjo Van Bergeijk says, farming continues. “Once the weather blows, I’ll be planting corn. That’s what I’m going to do.”