Incarceration, writes Angela Y. Davis in Are Prisons Obsolete?, “has become so much a part of our lives that it requires a great feat of the imagination to envision life beyond the prison.”

Those of us advocating prison abolition must grow our abilities to imagine radically liberated futures. Because visions of the future are informed by understandings of the past, historical analysis is an important part of that creative work.

Historian Lorna Poplak’s new book, The Don: The Story of Toronto’s Infamous Jail, unwittingly demonstrates how history books naturalize the prison, retroactively painting it as a necessary and inevitable institution. Although abolition is technically beyond the scope of The Don’s inquiry, the book is full of subtle rhetorical choices that justify or advocate incarceration.

The Don is a history of the “infamous” and eponymous Toronto jail, which was open from 1864 to 2013 on the east bank of the Don River. Poplak begins by retelling the role of incarceration in Toronto’s colonial past. Conveniently, by starting her history in 1793 with the British settlement of York, Poplak frames the narrative as one in which the existence of prisons is a foregone conclusion, pre-empting any interrogation of Britain’s carceral system. This move ignores thousands of years of Indigenous history, which would show that civilizations can thrive without prisons. Instead, in passing, she makes the bizarre assertion that prisons have existed “since time immemorial.”

Although abolition is technically beyond the scope of The Don’s inquiry, the book is full of subtle rhetorical choices that justify or advocate incarceration.

Poplak describes the 1824 decision to build a second jail to supplant then-York’s “dilapidated and comfortless” first jail (a log cabin with neither a source of heat nor a single bed), as one “urgently required” by the “expanding criminal element that accompanied [the town’s population] growth.” She doesn’t question or qualify her link between a growing population and its “criminal element.” By 1857, Poplak writes, Toronto’s third jail, which had only recently begun to allow its captives to sleep in beds rather than on the floor, was “straining at the seams” as the city’s population continued to swell. That year, during the financial crisis of 1857, architect William Thomas was commissioned by city council to build what would become the Don Jail. Poplak mentions Canada’s economic downturn to speculate that Thomas must have been eager to accept such a large assignment, without considering that the crisis, which some have called the first worldwide commercial crisis in the history of modern capitalism, might have impacted the perceived need for increased jail capacity. Poplak implies that all populations have a “criminal element” and that more people means more “crime” – in reality, though, “criminality” is a social construct shaped by a variety of factors including poverty, racism, and colonialism.

Alongside her credulous acceptance of the inevitability of prisons, Poplak reproduces value judgments that dehumanize incarcerated people. Starting with her retelling of the inefficient and expensive process of building the Don, Poplak spends more time and empathy writing about the men responsible for building and overseeing the prison than the people confined within it. She describes the writings and life experiences of duelling prison staff, vindictive politicians, meddling provincial officials, and variously negligent, ineffectual, and dogmatic governors of the jail, in many cases giving them undue credit for holding relatively “progressive” penal philosophies even if they failed to execute them. On the other hand, in her renderings of the jail’s captives, Poplak falls back on pat portrayals of conniving, manipulative, and irrational “criminals,” often describing them using racialized terms like “thug” and “hood.” These flat characterizations are certainly not helped by her reliance on sensational newspaper reports to narrate various acts of violence and jail breaks.

Ultimately, this leads her to present a history that offers full humanity only to those free to leave the Don at will.

To be sure, this uneven treatment of the jailed compared to the jailers may be due to imbalances in the historical record, since bureaucrats and politicians are more likely to make it into the archive – and more likely to be valorized when they do. But Poplak plays along, offering no critical analysis of the historical record’s imbalances. Ultimately, this leads her to present a history that offers full humanity only to those free to leave the Don at will.

Notorious for its inhumane living conditions, Poplak shows how the Don was the object of almost constant criticism from the time it opened. Poplak does not excuse the abusive conditions of the Don, noting its absence of lighting, heating, or plumbing in cells as well as its constant overcrowding, use of corporal punishment, and lack of good recreation or rehabilitation programs. For periods of the Don’s existence, Poplak writes, each year, “a new grand jury would denounce [the Don’s] plumbing, medical facilities and policies, its ‘non-existent’ correctional programs, and, sometimes, its dreadful cooking. On the city side, mayors had long decried it and at least one alderman had described it as a ‘hell hole.’”

In the book’s introduction, Poplak writes that what follows is “not an academic treatise on penal philosophy or Canadian correctional institutions,” but the story of “one small corner of the Canadian correctional system.” By choosing not to contextualize the abominable conditions at the Toronto jail within the broader network of Canadian correctional institutions, Poplak implies that the Don was just one “bad apple” in an otherwise effective and humane system – the exception that proves the rule. Although Poplak is right to dwell on the many indictments of jail conditions throughout the book, she does, perhaps inadvertently, imply that there is a humane way to punish people by locking them in cages.

The arguments propping up the expansion of the Ontario prison system are the same ones Poplak implicitly endorses in her book.

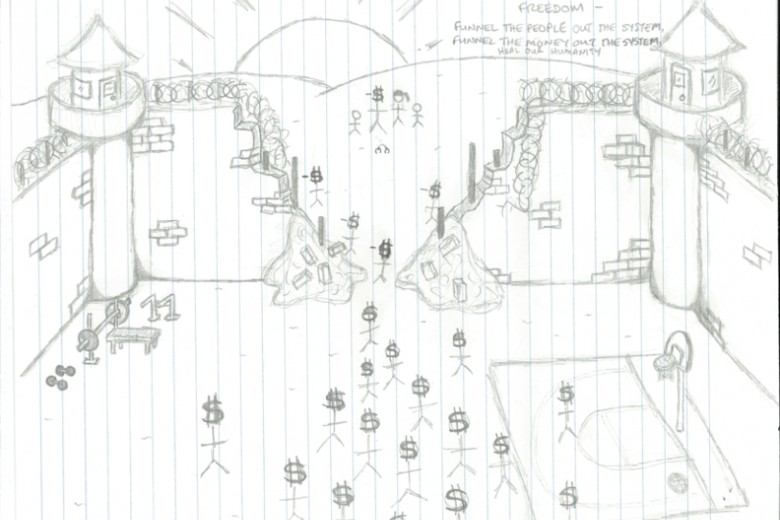

Today, new jails and prison reforms are justified with the same old rhetoric: that a certain fraction of any population is inherently criminal, that prisoners are subhuman, that prisons have always existed and always will exist, and that prisons can be made kinder and gentler. This past summer, Ontario announced its plan to spend hundreds of millions to hire more staff, renovate old jails, and build new “correctional complexes,” using “modern planning principles and design elements” to “fix the crisis in corrections.” This comes after years of public criticism by prison staff and the Ontario Public Service Employees Union as well as media coverage of complaints that portray prison guards as front-line soldiers in a war against prisoners. The arguments propping up the expansion of the Ontario prison system are the same ones Poplak implicitly endorses in her book.

Abolitionists can learn from Poplak’s work that it’s impossible for a history of a prison to disappear the continuity between one institution and the carceral whole. As The Don shows, the attempt to focus on one prison without its context reinscribes the very dynamics that gave rise to the prison in the first place – dynamics that, when left unchallenged, continue to fuel the expansion of the prison system.