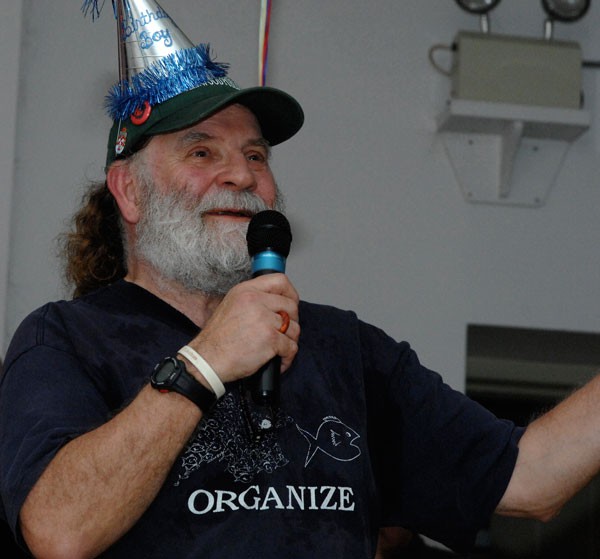

Book fair, awards show, or publishers’ banquet, Errol Sharpe is there with white beard and slicked-back ponytail, dropping quips that land with a thud. Since 1991, Sharpe has run Fernwood Publishing, a national small press swimming in an industry dominated by big fish.

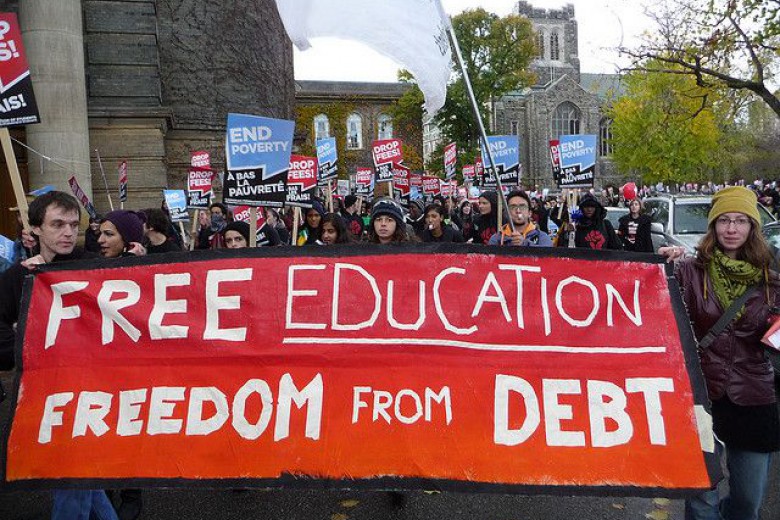

“The commitment was always to publish and sell progressive books that challenge the status quo,” Sharpe says. Riches don’t drive him, but opportunity does. He started out in Toronto, selling leftist books to academia in the ’70s. He noticed good, but radical, book proposals getting consistently rejected. “We began to publish the proposals that publishers did not.”

Sharpe started Fernwood soon after moving from Toronto to Halifax. It has since moved to Black Point, a coastal village in Nova Scotia. Fernwood opened a Winnipeg office in 1994 with Wayne Antony, who says joining the publisher was a political act. “We try to be politically active in other ways, from [how] we raise our children to being involved in alternative organizations.”

Fernwood maintains a radical, co-operative perspective. “I have come to see several of the other independents not so much as competition but as comrades,” Antony says. The competition – politically not financially – is big-box book production and sales.

The small company has had a significant impact, providing a unique opportunity for books that otherwise might sit on the author’s hard drive or imagination. “We often publish books that we don’t expect to make a profit if we feel it’s an important book,” says Beverley Rach, who runs Fernwood’s literary imprint.

As a result, Fernwood is a bit of an incubator for radical ideas, publishing many first-time authors who’d otherwise have difficulty publishing research that challenges conventional wisdom.

With more than 300 titles that significantly challenge mainstream thought, Fernwood is often quoted and referenced and is recognized as a major contributor to small-p political thought. Rach is tickled whenever she recognizes Fernwood writers’ ideas creep their way into big-P political platforms. But Fernwood is strictly non-partisan and fiercely independent. In that spirit, it supports other independent publishing ventures with its advertising dollars, which go to magazines such as Canadian Dimension and Briarpatch.

These are some remarkable accomplishments considering the enormous challenges faced by any small business, particularly one going against the grain in an industry where the money is funnelled into the pockets of few. Small markets, poor wages, and too great a workload for too few people have been challenging from the start.

Emergent technology has also brought challenges, but Sharpe says that threat is overblown. “All the surveys say people still prefer the printed book. Its death is wishful thinking by those who want a non-thinking population.”

Antony agrees, but he acknowledges that the medium may shift to e-books. “People will still write stories and others will want to read them. Keeping up … and figuring out how we will move into a more non-print era takes a lot of time and energy.” And these happen to be their scarcest and most overtaxed resources.

But the greatest challenge is the demise of independent bookstores. “The majority [of stores are] owned by Chapters in Canada,” Rach observes. “It dictates terms that make it almost impossible to sell through them.”

Amazon is equally difficult. Fernwood is one of the few companies that refuses Amazon’s demands for enormous discounts. But slaying Goliath takes more than a young king with a slingshot; it takes organization. Fernwood has begun talks with some booksellers and other publishers about developing an online alternative.

Fernwood is also going beyond its academic markets, hoping for greater flexibility to be radical. “We publish great books on important issues,” Rach says. “But because they are written for a university audience they are often inaccessible.” Enter the company’s About Canada series, giving radical national histories on health care, child care, and human rights issues.

Fernwood’s 2006 acquisition of Roseway Publishing is another step in the right direction. Fiction was a new venture, but experienced freelance editors like Sandra McIntyre in Calgary filled the gap. Roseway gives literary writers the opportunity to explore themes without being dismissed as didactic. That imaginative jolt is something the left needs. “There is wide dissatisfaction among many people with the society we live in,” Sharpe says. “Our books bring hope and analyses that point to a new society.”

More concretely, Fernwood has given hundreds of visionaries a voice they’d otherwise lack, taking financial risks many publishers avoid. “It’s neat to see so many other books reference Fernwood books,” Rach says. “We’re definitely building a new body of knowledge.”