On March 29, 2010, the Conservative government introduced new legislation designed to reform Canada’s asylum system, which governs the protection of refugees and their settlement in Canada. A key element of the proposed reform is the ability to deport individuals more quickly when their claims for asylum are denied. Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s news release and the subsequent news coverage of the issue openly played into public anxieties about immigrants taking advantage of the refugee protection system and costing Canadian taxpayers thousands of dollars in social service and health care costs.

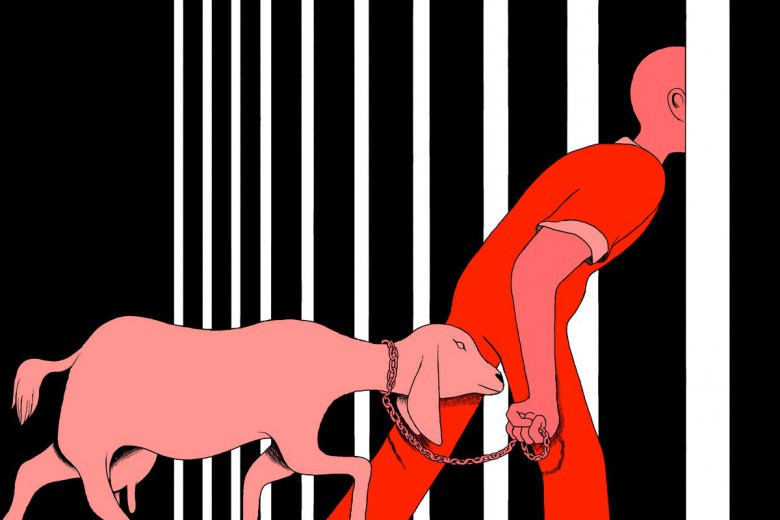

In this context, immigrants are reduced to their perceived economic worth, and are grouped into two categories: the “good” immigrant, who is educated, works hard and is grateful for the opportunities provided by a life in Canada, and the “bad” immigrant, the bogus asylum seeker or the unemployed immigrant who lives off of welfare and is unwilling to integrate into Canadian culture. Both are caricatures that the Conservatives have cultivated as part of a marked shift toward increasingly restrictive immigration policies.

The recently proposed changes to the refugee protection system are part of an ongoing process to ensure that Canada attracts more “good” immigrants (skilled economic migrants), and can more easily get rid of the “bad” ones (non-status migrants and refugees assumed to be of limited economic worth to Canada). The numbers reflect this emphasis: of the 250,000 immigrants admitted to Canada in 2008, more than two-thirds immigrated under one of the five economic classes for immigration. These include skilled workers, business applicants, provincial nominees, and foreign nationals with recent Canadian work experience. The eligibility criteria for these categories prioritize individuals with advanced degrees or skills in professions currently experiencing labour shortages, such as construction and nursing.

Attracting people to Canada based on their advanced education and skills sends the message that these “good” immigrants will be welcomed because of their capacity to contribute to the country’s economic growth. But real life is much different. Instead of being able to put their skills to good use, many immigrants find that their credentials aren’t recognized and their lack of “Canadian work experience” is a major barrier to finding employment in Canada.

A recent study of the Ontario Office of the Fairness Commissioner puts numbers behind these experiences: 26 per cent of internationally trained professionals in Ontario are unemployed, triple the rate of unemployment among domestically trained professionals. Those who do find employment are often hired in positions well below their skill and education level, earning less than half, on average, of what their Canadian counterparts earn.

Some say that in an economy that is barely moving out of a recession, we should focus on creating jobs for Canadians, rather than ensuring immigrants can find work. But both the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and Statistics Canada continue to stress that sustainable economic recovery and projected growth in Canada will depend, at least in part, on immigration and on ensuring that immigrants can find employment in Canada. Furthermore, despite the demonization of those who fail to meet the strict criteria for economic migration, the Canadian economy has become increasingly dependent on the ability to access a pool of highly exploitable, low-wage workers. But despite our reliance on the labour of non-status and temporary migrants, these “bad” immigrants continue to be denied the right to permanent residency or citizenship.

Immigration policies need to move away from simplistic paradigms of measuring individual worth. While immigrants are evaluated based on caricatures of their economic value, we don’t apply the same measure to Canadians, and for good reason. Yet, Canadians seem to feel entitled to demand that newcomers pass a rigorous test of presumed economic productivity, while denying them access to a standard of living that Canadians take for granted without ever having to pass such a test themselves.

In a country founded by immigrants who claimed rights to a land that wasn’t theirs, Canadians are hardly in a position to feel entitled to set the house rules about who gets to enjoy the privileges of life in Canada and who doesn’t. Our immigration policies must move beyond xenophobic caricatures and recognize that human worth is not determined solely by crude calculations of an individual’s economic value. Canada has an obligation to recognize the sacrifices of migrants who leave everything behind to make a life here, and should provide them with the same rights and supports as Canadian citizens.