When I was fifteen, I was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype. In the spring of 2004, I was sent to a treatment facility in North York, ON, where I stayed for four months.

I don’t tell people this story.

There are two reasons I keep this to myself. The first is that the treatment I received did more harm than good, effectively leaving me in a worse state of mental health than when I entered. The second is that, when I do tell people, they often give me The Look. They tilt their heads to the side, scan my body, and then draw a silent conclusion that leaves them baffled. You? Anorexia? You don’t seem like the type.

The “type” they’re thinking of is obvious, especially to those of us who grew up in the 1990s, when anorexia seemed to be an epidemic among teenage girls. The anorexic “type” is an upper-middle-class, white, thin, pretty, and popular girl, or else a girl striving for popularity. She restricts food intake to emulate models on TV and in magazines. She weighs herself constantly, idolizes thin bodies, and keeps pictures for “thinspiration.” Even if the anorexic doesn’t manifest her symptoms in all the stereotypical ways, she is always assumed to be a girl.

In the last few decades, the National Eating Disorders Organization, an American advocacy and prevention organization, has tried to deconstruct this monolithic idea of who the eating disorder patient is, demonstrating that eating disorders are prevalent among many demographics, although it is white women and girls who remain the most visible patients. Maisie Gard and Chris Freeman, among others, have published articles complicating ideas around eating disorder patients and race, socio-economic status, and sexuality. In spite of this research, eating disorder treatment centres still perceive most patients to be cisgender women. Even when boys are patients (as they were in my treatment centre), they are largely assumed to be cisgender. Patients who are transgender or gender non-conforming are virtually never considered; they remain invisible and underserved.

When I was hospitalized, this anorexic archetype was folded into the ways the medical staff treated me. Nurses would ask why I had starved myself when I was already pretty. Some would ask me for diet advice. Two weeks after I was hospitalized, I entered a day-treatment facility run by the same hospital, where fashion magazines, diet pills, and laxatives were contraband items. Therapy sessions were devoted to body image and discussions about the ways we (seven other patients and I) could be beautiful women without dieting.

How our culture defines womanhood also ends up being replicated in eating disorder treatment. Treating anorexia is about correcting the behaviour and adhering to a beauty stan-dard that is determined by the treatment team. This “right kind” of beauty standard becomes fraught and highly problematic when considering all the ways in which culture, ethnicity, body type (outside of weight), and sexuality end up defining who is beautiful and to whom.

I wasn’t the “typical” teenage anorexic because I wasn’t a cisgender woman. I was designated female at birth (DFAB), but it has taken me years to understand that my eating and exercise habits in my teenage years were a manifestation of gender dysphoria. Because of the way in which eating disorders are treated, however, I was never able to articulate this dysphoria. Instead, my therapy became a mission to become the “right kind” of woman, where doctors and counsellors ignored personal thoughts and preferences, along with the race, sexuality, and socio-economic status of patients. In order to leave the institution, not only did I have to have a normal body weight, but I had to have a normal feminine gender identity, too.

Ten years later, the only way I could comprehend my experience was to study it as well as write about it. Becoming the autoethnographer rather than an autobiographer allowed me to subvert The Look.

This is how it begins.

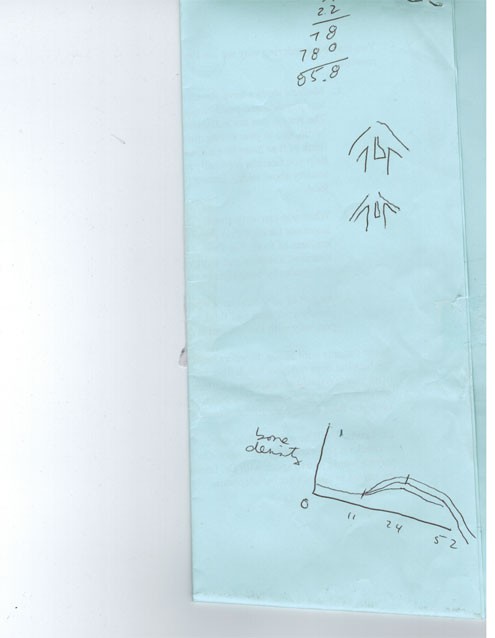

On my first day in the hospital, my doctor drew two images comparing the size of the heart in a healthy body and in the body of a patient with an eating disorder. A heart affected by an eating disorder is much smaller. “This is you,” she said, pointing to the smaller heart. “This is why you need to stay here.”

Because having an eating disorder is classified as both a physical and mental ailment, patients undergo medical and psychological monitoring. For a four-month period, I was assigned to a platoon of doctors, including a medical physician, dietician, psychiatrist, psychologist, and family therapist. I also had daily medical care provided by nurses and psychological monitoring from counsellors. These daily care providers acted as a middle ground between the patients and the doctors, thereby communicating most of the new rules in this sanctioned idea of womanhood. They monitored our bodies by watching as we ate meals, drawing our blood, and weighing us every day, but they also monitored how we interacted with one another, what we said, and what we thought about our treatment. It was made clear early on that not only was I here until I was healthy both physically and mentally, but also that my hospitalization was my own fault.

The subtext of blame drives the language of eating disorders (ED). Most doctors diagnose ED patients with some version of “distorted body image” or body dysmorphia, a term that means that patients imagine their bodies to be abnormal or ugly; very often, the term refers to people who think they are fat even though they are thin. Though this language is common among health-care providers, not every patient with an eating disorder has a distorted body image. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V – a manual used by psychiatric professionals to adhere to standardized diagnoses and treatment, currently in its fifth edition) treats body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) as distinct from eating disorders; that is, while they are sometimes co-morbid cases, they are not the same illness.

But when I was receiving treatment, BDD was conflated with anorexia. Against the backdrop of public messaging (such as commercials about anorexia, high-school curricula, and other popular sources representing the illness) that often frames the anorexic as having a faulty version of reality, the distorted body image label stuck with me and other patients, and our counsellors and nurses regularly doubted us.

Because the label of “distorted body image” assumes that the patient’s thoughts are wrong or overblown, treatments became small acts of humiliation that discipline the patient into acting according to institutional expectations of the “cured” anorexic. On my first day in the in-patient facility, I was forced to eat butter from the container because my counsellors thought I was lying about my food intake (though I never refused food). Before the twice-weekly weigh-in, we were told to strip down to ensure we didn’t keep rocks in our pockets to throw off the scale. If we didn’t eat quickly enough at mealtime, our counsellors reminded us we could get “The Tube” (the gastrointestinal tube designed to go into a patient’s throat and deliver a liquid meal). Most of these rules had nothing to do with our physical states and everything to do with our perceived mental states. In extreme cases, patients do need doctor interventions, but the counsellors in our day-to-day therapy groups used discipline measures like The Tube as a way to ensure that we complied with activities, not as an intervention for survival.

When our therapy sessions were cancelled and I opted out of the sanctioned free-time activities of painting nails or watching romantic comedies, I was labelled a troublemaker. I was routinely brought into separate rooms and asked point-blank by the counsellors if I wanted to be thin. I wouldn’t be allowed to leave until I said yes; to the counsellors, wanting to be thin was the only conceivable and acceptable reason for resisting their treatment. There was no room for nuance.

The day I ate butter, like the day my heart was drawn three sizes too small, I was given a very clear message: in order to leave, you need to gain weight, but you also need to fundamentally change who you are and how you behave.

So I did.

I was the first of the seven patients to leave. On my last day, the remaining patients made me a card and wrote me goodbye letters.

Their card reflects the basic dynamic of our therapy. For a period, we lived in a strange, insulated world called The Program, where we were constantly monitored, disciplined, and humiliated, all for the purpose of re-entering The Community. The Community was the outside world, where magazines and diet foods still existed, but because we had been reprogrammed by The Program, we’d supposedly be able to resist the threats. Since I was the first person to re-enter this brave new world, I was seen as the epitome of success, and as the epitome of proper womanhood.

After our last meal together, we all said teary goodbyes in the foyer of the treatment centre. But my mother, who was going to give me a ride home, was stuck in traffic. In that moment of being in between The Program and The Community, I realized I was utterly alone, and I did something ridiculous: I turned around and went back inside the hospital. I ran into another girl named Valerie,* and I said hello to her again.

Valerie waved, but the look she gave me asked, What are you doing here again? Get out. Go home.

Eventually, when my mom came, I did.

But I think about turning around and saying hello to Valerie a lot. I resented my treatment in this place, yet I turned around the moment I was free. Why?

I understand now that when in that moment of being alone again, there was only one thing left to feel: the anxiety that got me in this problem in the first place. I had become the version of womanhood the doctors wanted me to be, yet it was completely counterintuitive to what I wanted and needed.

My gender dysphoria overwhelmed me and I longed to get rid of the feminine attributes that had returned upon gaining weight – like breasts, fuller hips, and menstruation.

Being underweight at a young age delays puberty because a DFAB body in starvation mode slows its production of estrogen. While I was in this state, I had the time to not identify as any gender at all. It wasn’t a healthy way to deal with dysphoria, but that should have been a red flag to any physicians familiar with transgender issues. But because no one considered anything outside of the standard eating disorder narrative of failed femininity, I was treated as a little girl who needed to grow into my body and learn to love my womanhood.

Over the next few years, I lost and gained and lost weight again until I was 23 and came across the identities of transgender and non-binary. I stopped telling the story of being an eating disorder patient with distorted body image, and started to tell a version of my transgender autobiography. I thought I had to deny the eating disorder and claim that my behaviour was a result of being trans; it felt too risky to share the humiliation I felt in treatment, especially since I became the beautiful woman my physicians and counsellors wanted me to be (and I performed this identity for almost a decade afterward). Telling anyone about The Program and everything that had happened to me would only conjure The Look and make me explain my gender again.

But my eating habits can’t be dismantled from my gender identity; they are intimately linked because they provoke one another. Being underweight was my version of transitioning before I understood what transitioning was. Gender is more complicated than wanting to be a man or a woman, and similarly, eating disorders are far more complicated than wanting to be supermodel-thin. Because food intake affects bodies and hormones, it inevitably affects the patient’s gender presentation; this aspect of eating disorders cannot be overlooked by physicians and health-care professionals. Even for the cisgender girls in my treatment facility, there was little to no variation available to them in their own gender presentation; everyone had to follow a script of healthy femininity that was shaped by assumptions embedded in medical literature and popular perceptions of eating disorders. Whether we were cis or trans, we were all treated as liars and deceivers; all of us had our privacy and bodily autonomy taken away, and we were all slotted into a reality where only The Program and The Community existed.

This was not a good model for treating eating disorders. By not providing other treatment options or examples of healthy behaviour for patients to identify with, the institution became the problem it sought to solve: it enforced a monolithic idea of standardized femininity that had a long-lasting effect on me.

In the intervening years, some treatments for eating disorders have changed, and they will likely continue to improve. I don’t doubt that my team of doctors wanted to help me, but the way they tried to do this highlighted the damaging way eating disorder patients are conceived in medical literature and within institutional walls. Until gender nuances are integrated into treatments of eating disorders, cases like mine will continue to happen.

And I don’t want to tell this story anymore.

*Name has been changed.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)