In Black Disability Politics, Sami Schalk provides an easy-to-understand historical account of Black disability organizing in the U.S., revealing how issues of disability have been central to Black activism from the 1970s to the present. The book is an offering for Black people, particularly Black disabled people. Schalk makes that clear in her introduction with a special message to Black readers: “Welcome. Settle into the space. Mark the pages. Make it yours. Pass it along.”

There’s a misconception in mainstream disability rights movements that Black people are uninterested or uninformed about disability organizing. In the disability studies classes I took on the fight against psychiatric institutionalization, Black people were rarely, if ever, discussed. The history I was taught was: white people wanted out of the institution, while Black people were never let in. Therefore, Black people weren’t a part of movements protesting psychiatric abuse.

Sami Schalk challenges this narrative in Black Disability Politics, digging into the archives of the Black Panther Party and National Black Women’s Health Project and finding that not only were Black people protesting institutionalization and ableism, but that disability justice has always been central to Black radical organizing; it just wasn’t recognized by white mainstream disability rights movements.

There were many Black disabled organizers before me and we have always and will always play a central role in the disability justice movement.

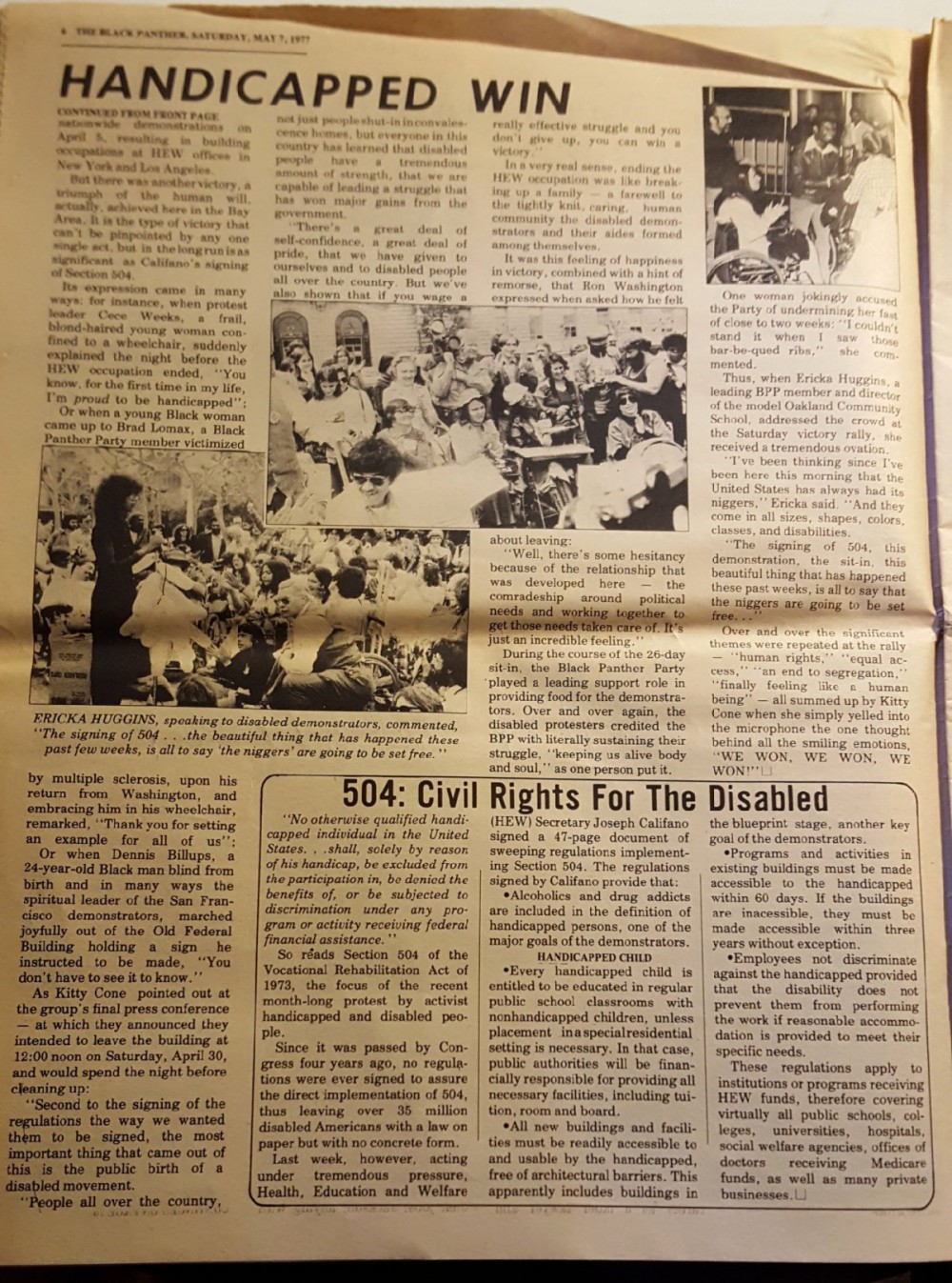

Contrary to the lessons I learned from my predominantly white disability studies professors, Schalk writes that Black people were institutionalized alongside white people. Inside the institutions, Black patients were forced to perform unpaid labour, coerced into pharmaceutical treatment, and subjected to electroshock therapy, psychosurgery, and other harmful practices. The Black Panther Party was heavily involved in organizing against institutionalization and patient abuse, working directly with patients and their families.

The Black Panther Party’s exclusion from historical accounts of anti-psychiatry organizing was partly caused by a difference in language, Schalk explains. Despite organizing at the same time as anti-psychiatry, Mad Pride, and consumer/survivor/ex-patient (c/s/x) movements, the Panthers’ organizing wasn’t recognized, because they “understood the relationship of racism, classism, and ableism, but their approach to disability politics did not always align with the language and tactics of the white mainstream disability rights movement.”

To describe Black psychiatry patients subjected to inhumane treatment like electroshock therapy, the Panthers used the term “vegetable,” a slur describing a disabled person with consciousness but limited ability to move. It implies that the person’s life has less meaning or purpose than a non-disabled person’s.

Schalk agrees that the use of the term was ableist and doesn’t defend its use, but she does take care to explain the context. The Black Panthers first used the word vegetable in an article published in January 1973 to argue that the state was using psychosurgery to save money on prisons and send people “back into society as vegetables” instead of incarcerating them. The Black Panther Party understood that institutionalization and psychiatry were other forms of violence inflicted on marginalized people by the state. By using the term, the Panthers were trying to describe the cognitive functioning and decline inflicted on young, Black, politically-active men by medical institutions.

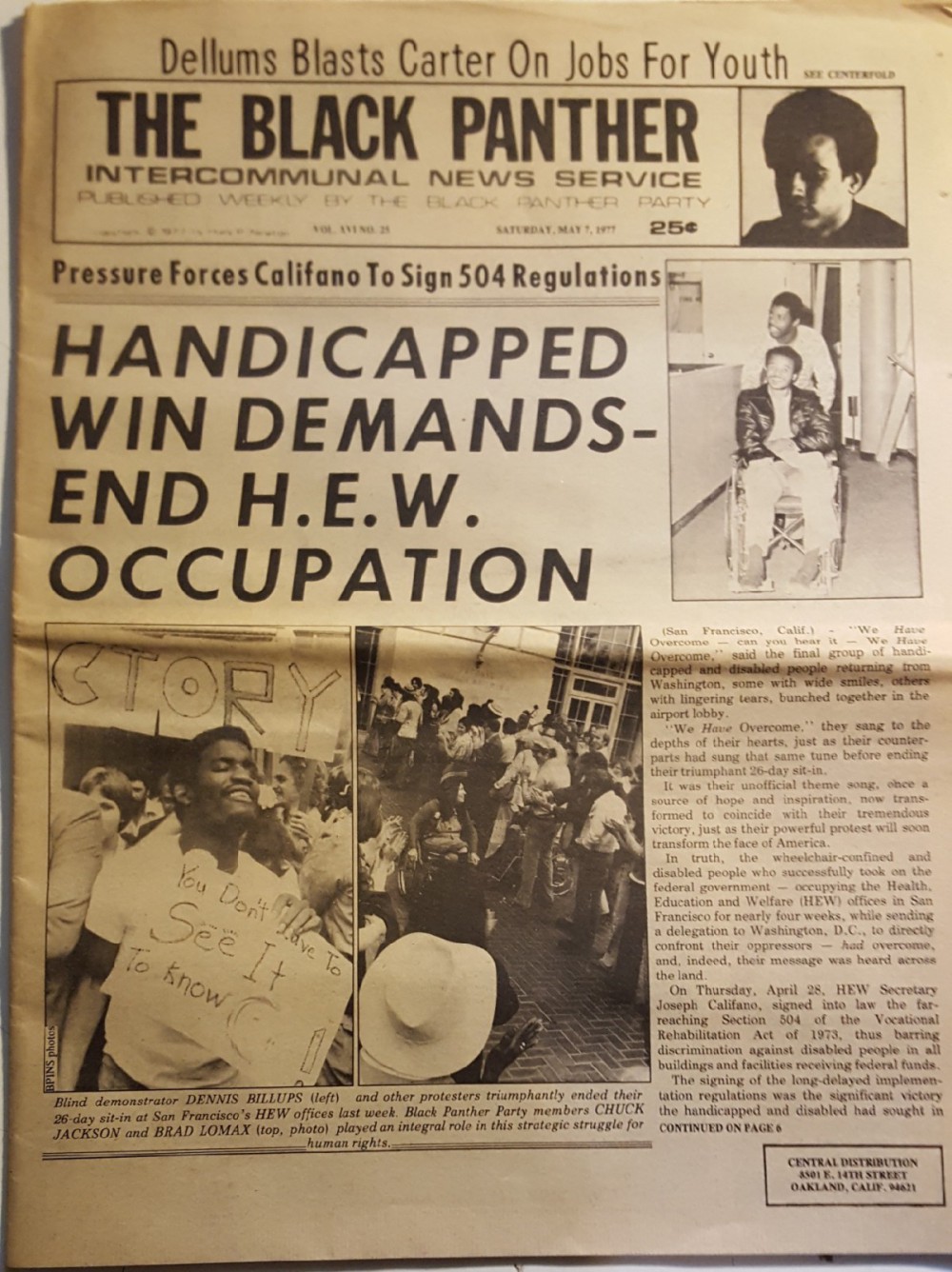

Photos of the Black Panther Intercommunal News Service. Photos courtesy of Billy X Jennings: Black Panther Party archives

Despite these differences in terminology, Schalk concludes that it’s indisputable that the Black Panthers showed solidarity with disabled people. One of the most notable examples is the Black Panthers’ support for the 504 Sit-In, when disabled people occupied government buildings to demand accessibility legislation.

I learned about the 504 Sit-In in a disability studies class taught by a white instructor. I learned that the occupation was a pivotal moment in the disability rights movement. It was the longest non-violent occupation of a U.S. federal building, lasting from April 5 to April 28, 1977, and helped pave the way for the Americans with Disabilities Act.

But it wasn’t until graduate school – in a disability studies elective taught by Dr. Agnès Berthelot-Raffard – that I learned about the integral role the Black Panther Party played in the 504 Sit-In, including providing food and water to protestors and bargaining with police.

Berthelot-Raffard’s class was an outlier in my disability studies education. My studies introduced me to critical disability theory which helped me identify as disabled in my early twenties. I hadn’t previously, despite my lifetime of experience with long-term disabilities and anti-Black, ableist, and saneist oppression.

Disability justice has always been central to Black radical organizing; it just isn’t recognized by white mainstream disability rights movements.

Disability studies classes also introduced me to the anti-psychiatry, Mad pride, and c/s/x movements, which deeply resonated with me and my lived experiences with what I now understand to be psychiatrization and anti-Black saneism. I read patient journals, engaged with Mad art created by asylum patients, and learned about the unpaid patient labour that built the former asylum now known as the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto.

But I struggled to locate the role, contributions, or lived experiences of Black people within Mad and disabled movements. I left class with unanswered questions about Black people’s political and scholarly contributions to critical disability theory and organizing. I did not see us represented, and began to wonder if my interest in disability studies would isolate me from Black community.

But in Berthelot-Raffard’s class and Schalk’s book, I learned that there were many Black disabled organizers before me and that we have always and will always play a central role in disability justice organizing. Liberation movements across the globe can benefit from the research, attention to detail, and care Schalk put into documenting a disability politic that centres the tactics of Black feminist disability organizers, advocates, healers, activists, and scholars.