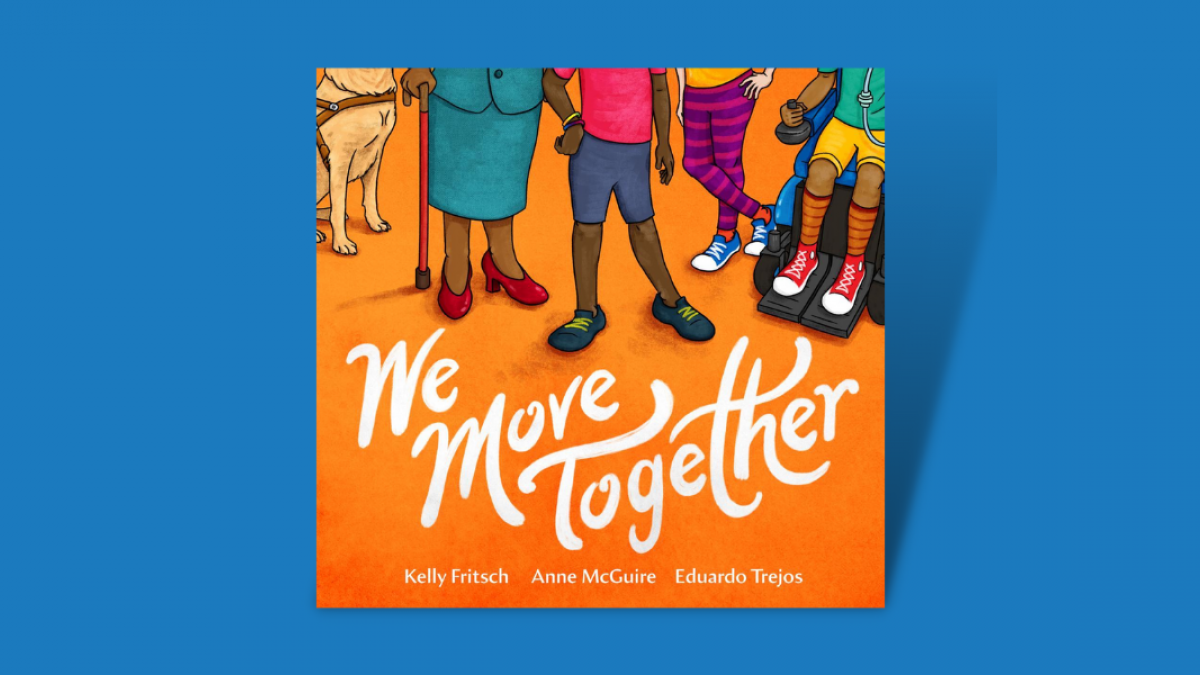

We Move Together is a children’s book about people navigating their neighbourhoods and making friendships along the way. It’s an excellent book for teaching kids about disability, accessibility, and co-operation. It conveys that everyone has something special to offer and that we can all help each other out.

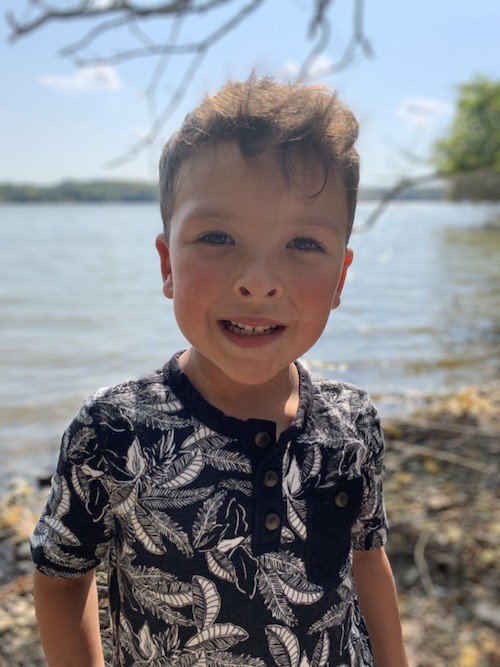

The book is aimed at a younger audience and we thought it was important that children be the ones to review it and provide honest feedback. After reading the book, each child was asked a set of questions, which varied depending on their age, and their responses are compiled here. The book reviewers are Aisha, age 6; Isabelle, age 6; Langston, age 6; Divya, age 9; Adam, age 12; and Mary, age 13.

What are some difficulties people using mobility devices faced while travelling to stores in this story?

Langston: There were steps to get into the store that the lady in the scooter couldn’t get up and there were things in the store she couldn’t reach. I think the group of friends felt sad.

Divya: At the ice cream shop there are no ramps so people with wheelchairs can’t enter.

What were some of the solutions the community came up with to help them overcome these difficulties?

Isabelle

Isabelle: They created ramps so everyone could go in.

Langston: They had ramps on the sidewalks, and there was a store that had a window to get food instead of having to enter through a door. In the grocery store, someone helped a person who couldn’t reach food and I bet that made them feel really happy.

Can you spot the different ways people are communicating at the grocery store?

Divya: Some of the different ways people communicated at the grocery store were by using sign language and pointing so that they could get help.

Langston: I see someone pointing to what pepper they want. Oh, and the cat is communicating by saying “meow meow.”

What are some ways in which society could improve on open communication with those unable to speak or hear? Could technology play a role?

Adam: You can use websites and apps to spread awareness because lots of people will see it and they will spread awareness too.

Mary: One way society could improve communication with people who are Deaf or hard of hearing is by implementing more American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters in public places such as hospitals, government buildings, and courtrooms. This would allow those who are Deaf or hard of hearing to have full access to important services. Another way to improve communication accessibility is by developing technology that can translate spoken words into ASL.

Cities and communities are built around certain building codes and bylaws. When people face a barrier, it is because the codes and bylaws failed to consider their equitable access to spaces. Name some obvious physical barriers in your neighbourhood that may prevent people with disabilities from fully gaining access to spaces or places.

Adam: Places need elevators and ramps because at some schools there are only stairs. That barrier stops you from getting into classes and that will affect your grades.

Mary: When I go around my neighbourhood, I see a lot of things that make it hard for people with disabilities to get around. For example, there are a lot of storefronts that have steps instead of ramps, and there are also a lot of sidewalks that are cracked and uneven. These things make it really hard for someone in a wheelchair or using a walker to get around. It’s important for cities and communities to be more inclusive and to make sure that everyone can access the places they need to go.

What’s one change you’d like to happen to help improve your neighbourhood?

Isabelle: I would like to see every store have wheelchair ramps.

Langston

Langston: People should make cars that wheelchairs can fit in so that wheelchair users can drive the car by themselves. Instead of stairs going up to bedrooms, there should be ramps or elevators. When it snows people should shovel the sidewalks, and wheelchairs should have umbrellas on them for the rain because some can’t get wet. Slides should be wider and there should be a ramp to go to the slide so people in wheelchairs can go down the slide.

Divya: One thing I would change to improve my neighbourhood is to add swings to the park that people with wheelchairs can use.

Adam: I’d like people to show more awareness about accessibility because it would make a big difference in a good way. We can help solve accessibility problems by adding elevators and ramps in buildings so people can finally access the places they need to go. Sometimes people use the parking for people with disabilities even if they don’t need it, and that makes it hard for people who actually need it. If they add more parking spots for people with disabilities and more spots for people without them then they will stop stealing those spots.

Mary: I would widen the sidewalks in my neighbourhood because right now they are too narrow for wheelchairs, scooters, and walker users. I have seen a person in a wheelchair almost tip over because the narrow sidewalks caused the wheelchair to be unsteady at the driveway slants. I would also make sure all crosswalks are equipped with disability-friendly features like audible signals and tactile paving. Also, I would make all the parks accessible to all children so everyone can play. Right now, there’s no way for children with physical disabilities to use the equipment at the park in my neighbourhood. The city should consult people with disabilities when building new parks.

What’s one thing you liked about this book?

Aisha

Aisha: The book was about fairness, and the pictures were nice.

Isabelle: I really liked that they showed kindness.

Langston: It tells a story about disabled people and hopefully when people read it they will start doing things like shovelling their sidewalks so people can walk and scooter without falling.

Is there anything you didn’t like about the book?

Aisha: No.

Isabelle: I didn’t like that Luke Anderson couldn’t go into any stores in his neighbourhood.

Langston: No, actually, there isn’t. It’s the greatest book on Earth.

Divya

Divya: There is nothing I didn’t like about this book.

Adam: When I was reading the book, I didn’t see anything that would need to be changed, so it is perfect as it is.

Mary: I wouldn’t change anything about this book. It was fun to read, the pictures were nice and bright, and on every page there was so much to look at and think about. I think any kid would enjoy this book.

To the parents who are reading Briarpatch, what do you want them to know about this book?

Adam: This book should be read by all kids because it can educate them at a young age that everyone is human and they shouldn’t treat kids or anyone differently just because they have a disability.

Mary: Parents should know that this book will help kids to understand how our bodies work and that we should accept others as they are. This book should also be in all classrooms and libraries so everyone can read it and because there needs to be more books that show people with different abilities.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)