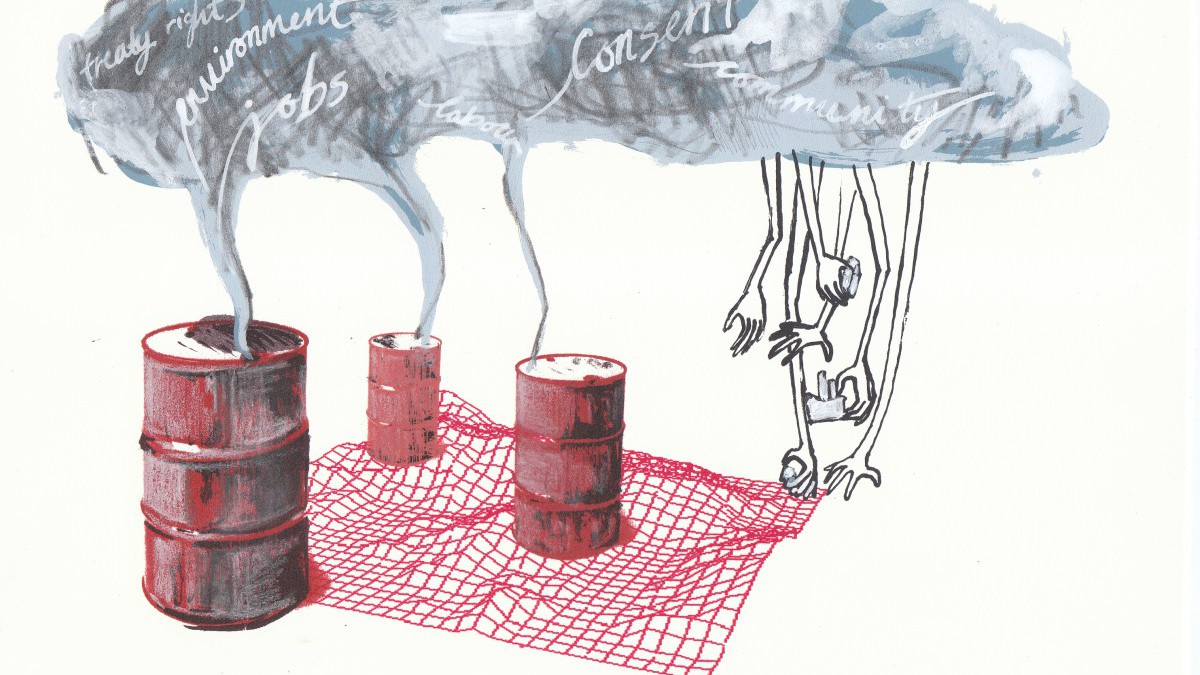

This is my first offence, ever,” Vanessa Gray told the crowd gathered outside a Sarnia, ON, courthouse on the chilly morning of January 26, 2016. The member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation continued, “We have plenty more court dates to go now. But I’m happy to have locked down to Line 9 and to take action against this company [Enbridge] and this project [Line 9] that impacts my community along with other communities, that walks over Indigenous rights for profit.”

Gray and two others involved in the action, Sarah Scanlon and Stone Stewart, were charged with mischief endangering life for having turned off a valve of a major Enbridge pipeline carrying tarsands and Bakken crude oils from Sarnia to refineries in Quebec.

Scanlon also addressed the crowd that morning: “Remember the original messaging that we put out before locking down: this pipeline is happening without consultation, without consent,” she said, referencing the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation’s Supreme Court challenge against Line 9 and the National Energy Board.

The stakes in the case against Gray, Scanlon, and Stewart are high: the charge of mischief endangering life comes with a maximum penalty of life in prison.

Enbridge’s proposal to pump western oils through its 40-year-old Line 9 pipeline was put forward in 2011 and 2012, and quickly garnered opposition from Indigenous peoples, environment-al activists, and municipalities. Pipeline expert Richard Kuprewicz published a report demonstrating a high risk that the reversed Line 9 will rupture when carrying diluted tarsands bitumen.

The proposal was approved, with conditions, in March 2014. In December 2015, oil began flowing through Line 9.

Gray, Scanlon, and Stewart’s manual shutdown of Line 9 in December 2015 was inspired by a similar action two weeks earlier, on December 7, when protesters shut down Line 9 in the town of Sainte-Justine-de-Newton, a town on the Quebec side of the border with Ontario.

In both instances, protesters broke into a fenced-off area above ground and secured themselves to the valve with bike locks around their necks. The protesters were filmed in the act, and they were later removed and arrested by police.

Two anonymous shutdowns, one of which targeted Line 7, also occurred in January; the second action happened the day before the Sarnia court appearance.

Why is the fight against pipelines so important?

Pipelines in the colonial project

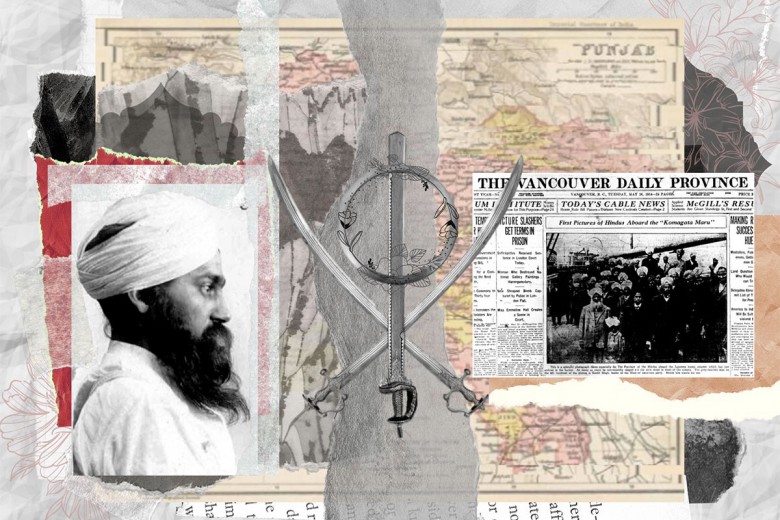

Line 9 was built in 1976, 100 years after the introduction of the Indian Act. That legislation continues to dictate how the Canadian state treats First Nations, and it has been amended extensively to simultaneously assimilate First Nations and limit their freedoms through extensive and paternalistic regulation of their governance, land base, and identity.

One group of amendments in particular, known as the 1911 Oliver Act, made it possible for public authorities, including companies and municipalities, to expropriate reserve lands for public works without a surrender of lands.

The land of Aamjiwnaang First Nation, near the location of the December 21 Line 9 shutdown, measured over 4,000 hectares in 1827. Through a series of illegal land transfers and transfers made legal through the Indian Act, it was reduced to its current 1,254 hectares. Much of that land was transferred under coercion, first to the Canadian government, then to the city of Sarnia and several corporations, like Dow Chemical and Enbridge. The area is now known as the Chemical Valley and has some of the worst air pollution anywhere in Canada.

Mount Elgin Industrial School, which one survivor describes as “living in a prison” and which doubled as a forced labour work-farm, operated from 1851 until 1946, 30 years before Line 9 was built. Located in the First Nation of Deshkaan Ziibing (also known as Chippewas of the Thames), east of Aamjiwnaang along the Line 9 route, Mount Elgin was part of the residential school system designed to “take the Indian out of the child.”

One effect of this system was a weakened resistance to pipeline development, including Line 9, in the 1970s. “Your only chance for survival was to forget about your language and culture, your history, your past,” former Deshkaan Ziibing chief Joe Miskokomon told the Toronto Star. “Many people believed that it was true, that maybe we don’t have any rights, maybe there is nothing left.”

Oil extraction in western Canada, the source for oil products transported through pipelines like Line 9, is similarly trampling Indigenous treaty and land rights. “Tarsands operations are in violation of treaty,” says Jesse Cardinal, a Métis activist from Kikino Métis Settlement, northeast of Edmonton.

“They are destroying the ability to hunt, fish, and trap, which is a treaty right. [They are] also destroying navigation on the land. Indians used to roam free – it was stated in the treaty that they could continue to do so.”

On the day she shut down Line 9 near her home in Aamjiwnaang, Gray said, “The tarsands projects represent an ongoing cultural and environmental genocide. I defend the land and water because it is sacred.”

Getting to know the National Energy Board

Authority over pipeline projects, from Canada’s perspective, is vested in the National Energy Board (NEB). Established in 1959, the NEB is mandated to “regulate aspects of the energy industry under federal jurisdiction,” which includes pipelines crossing provincial boundaries, like Line 9 in Ontario and Quebec, and Northern Gateway in Alberta and B.C.

The dozen or so members of the NEB are appointed by the federal government, and the Board is known to be stacked with former oil industry insiders, the majority of whom are white men. Headquartered in Calgary, the NEB operates at arm’s length and does not take direction from Parliament. It deliberates on applications, like the one Enbridge submitted for Line 9 in 2012, and delivers its decisions to the Canadian government.

Jean Léger, one of the three activists who first shut down Line 9 at the Sainte-Justine-de-Newton site, says in French, “I didn’t have any experience with the NEB before 2012. When I learned there was a pipeline going to be reversed to carry tarsands three kilometres from my place, we got people together.”

The spectre of tarsands coming to Quebec through pipelines had hardly registered in la belle province before Enbridge’s 2012 application. Line 9 had been operating in the opposite direction, carrying foreign oils from Montreal to Sarnia, since 1998. Then, as industry planned to increase tar sands extraction in Alberta, Enbridge submitted a proposal to the NEB to reverse the Line 9 flow to carry carbon-intensive bitumen from west to east.

Along the line, people began mobilizing, with many participating in the NEB process. First Nations and many other groups spoke against Line 9 at NEB hearings, while Unifor, a large union, came out in favour of the project.

Others chose to stay out of the NEB process, applying pressure in other ways. “The NEB is totally rigged to be an undemocratic rubber stamp of public infrastructure projects,” writes Lily Schwarzbaum of Climate Justice Montreal. “We were skeptical from the start, although we supported citizens who were trying to go through the process, in the (realized) hope that they would be radicalized through the process.”

In 2012, when Stephen Harper’s Conservative government introduced changes to the Navigable Waters Act through omnibus Bill C-38, pipelines were removed from an approval process that had previously been established to protect navigable waters from construction projects. With these changes, pipelines could now pass through waterways without federal oversight. Further changes entrenched through Bill C-45 (the omnibus bill that helped spark Idle No More in December 2012) meant that ex-oil executives on the NEB, rather than government scientists, became the experts making decisions about pipelines. When all was said and done, Green party leader Elizabeth May remarked, “The NEB is now basically a pipeline approval agency.”

Justin Trudeau was also critical of the NEB. “We will restore a level of independence and intellectual rigour, if you like, to the processes of boards like the National Energy Board,” he said during the federal electoral campaign in August 2015.

Now in power, Trudeau’s Liberal government’s proposed NEB changes have not satisfied regional First Nations chiefs of Quebec, Manitoba, and B.C.

Opposition along the Line

In Toronto, where “Stop Line 9” signs featured prominently at protests, in windows, and on lawns, the municipal government showed distrust in the NEB’s ability to protect waterways. In April 2014, a month after the NEB had given approval for the project, Toronto city council voted 28 to 4 to ask the Province of Ontario to ”conduct a comprehensive environmental assessment of the Enbridge Line 9B application,” the mandated job of the National Energy Board.

The year before, in the Beverly Swamp, the group Hamilton Line 9 organized the “Swamp Line 9” campaign, a blockade of an Enbridge pumping station. While 18 were arrested, solidarity actions were held in 13 cities around the country.

The next year, in 2014, near Woodstock, ON, an organization called Dam Line 9 again put the pipeline on the radar. Coordinated by organizers in Toronto, Guelph, Kitchener-Waterloo, and Hamilton, people blocked Enbridge from conducting integrity digs, thereby delaying the company’s plans to ready the pipeline.

Then, in fall 2014, three Quebec women blockaded an entrance to the Enbridge facility in Montreal for a morning after 200 activists from “Camp Ligne 9” gathered at a farm along the pipeline route. The action made front-page news in francophone papers like Le Devoir.

Line 9 starts pumping

The NEB, watching the mounting opposition in Quebec, met with Montreal mayor Denis Coderre in January 2015 and announced it would open an office in the city to improve relations with the population there. During the announcement, according to the mayor’s office, “Mr. Coderre congratulated the Board for requiring Enbridge to consult with the municipalities involved in project planning and implementation.”

Later in the year, with continued public pressure and a request from the Montreal-area mayors, the NEB mandated some sections of Line 9 to have hydrostatic testing to check the pipeline’s integrity.

“Lots of municipalities dropped their opposition [to Line 9] after the hydrostatic testing,” says Léger. “It was a way for them to show they were satisfied, even though the testing didn’t show much.”

Léger is still concerned that safety issues remain unresolved. “I asked in communities around me,” he says, listing Argenteuil, Deux-Montagnes, and Mirabel. “No one working for the towns knows the emergency procedures. If a spill happens in winter, under the ice, there’s no method to clean it up. Why is this acceptable?”

Léger says that the actions he took on December 7 to shut down Line 9 “happened because we had used up all our other means of pressure advancing our cause against Enbridge.”

In the shadow of Energy East

Even before Line 9 was reversed and began flowing again, the pipeline conversation in the area changed with TransCanada’s Energy East pipeline proposal, publicly announced in August 2013. If built, Energy East would be the largest tarsands pipeline by volume, transporting 1.1 million barrels per day (total tarsands production was 2.3 million barrels per day in 2014).

Energy East would use an existing natural gas pipeline stretching from Alberta to the Quebec border but would require new construction through Quebec and New Brunswick. It may be years before it is approved, given that the NEB asked TransCanada to edit and simplify its application in February 2016.

As Léger puts it, “Some people said, ‘It’s too late for Line 9, it’s too late for Enbridge, it’s already done. Turn your attention to Energy East and let’s try to stop TransCanada. It’s bigger, it’s not already all the way built, there [are] better chances fighting there.’”

Resistance to Energy East may be reinvigorated among proponents for domestic refining, such as Unifor, that previously supported Line 9. Given that Line 9 supplies Montreal-area refineries almost to their capacity, most additional pipeline capacity driven by Energy East will be used to export unrefined product, even if some refining happens at the Irving facility in New Brunswick. Unifor has yet to take a position on Energy East, but in 2015, it made official arguments against Northern Gateway, an export pipeline on the west coast.

In early March of 2016, the Line 9 fight returned to the headlines as the Supreme Court of Canada notified Deshkaan Ziibing (Chippewas of the Thames First Nation) that it would hear their case. A lower court, by a decision of two to one in October, had dismissed the First Nation’s argument that the NEB did not fulfil its constitutional and treaty duties to consult on the Line 9 reversal.

As Chief Leslee White-Eye said to the CBC, “We need to bring home that we are not acting alone in the action, nor that it is for our sole benefit, but an attempt to seek protection of our water – these energy developments are one of many across the nation impacting our rights.”

It remains to be seen whether any changes will come from the Trudeau Liberals’ promises of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. But what’s sure to endure is resistance to Line 9 and other colonial projects operating on Indigenous lands without Indigenous consent.