Cee Lavery

From Palestine to Turtle Island, publications and media platforms that support oppressed groups around the world against all-encompassing systems of violence have used the term “genocide” to name how violence manifests not only in direct physical harm against marginalized people, but also in the removal of health care, housing, and other essential forms of support. As two transfeminine writers of colour, we know that genocide accurately describes the ongoing onslaught against our trans, non-binary, Two-Spirit, and other gender-marginalized peers and kin on both sides of the increasingly fragile colonial border between so-called Canada and the U.S. However, the word does not capture all that’s at stake in the fight for our communities’ collective future. Journalists must learn from their profession’s egregious errors in sensationalizing trans lives and erasing our histories, and refuse to normalize the destruction of our very existence and memory in public discourse.

Tipped Out of the Frying Pan

Though the writers of this article graduated high school over a decade apart and on opposite ends of Canada, we both routinely heard ineffective messaging around movements for trans rights and visibility. Celeste saw posters plastered in her schools in Quebec in the late 2010s that denounced homophobia and transphobia using language similar to that advocating for gender equality between cis men and women. She felt this rhetoric was easily dismissed by overwhelmed and overmessaged students – and she herself didn’t realize that these messages had personal meaning to her until she came out years later. Meanwhile, when Serena graduated in B.C. in 2011, her high school lacked what was then called a Gay-Straight Alliance (now, Gender & Sexuality Alliance) or other extracurricular programs to support LGBTQ2S+ students.

Outside of our limited adolescent understandings of the political landscape, the 2010s also saw publications across Turtle Island begin in earnest to report on burgeoning transgender rights movements in Canada and the U.S. In January 2014, Maclean’s published an article headlined “What happens when your son tells you he’s really a girl?” that framed transgender youth as a novel phenomenon and reported how Canadian authorities and other organizations had begun to enforce trans inclusion. “Unbeknownst to most people,” the article’s fifth paragraph begins, “over the last few years many organizations have transformed the rules, policies and practices pertaining to gender variance – in effect, mandating and legislating acceptance and accommodation.” While the magazine has improved its approach to reporting on trans individuals, including publishing one article in 2024 by a transfeminine Calgarian about coming out in her 60s, coverage in Maclean’s still lacks a foregrounding of the systemic nature of the threats we face.

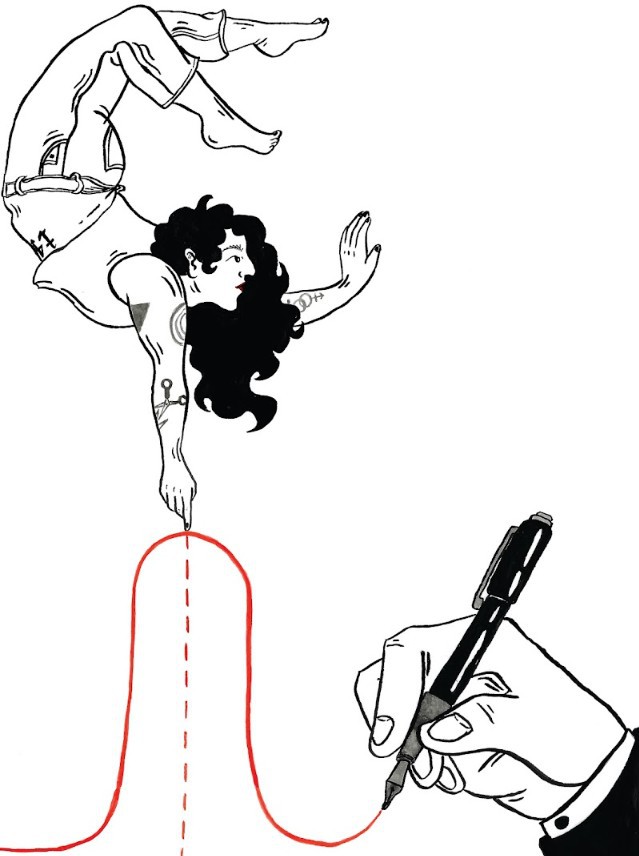

In May of 2014, TIME ran a cover story featuring Laverne Cox titled "The Transgender Tipping Point" that became (in)famous in trans communities and beyond. Although it foregrounded civil rights, TIME’s article may have also provided reactionaries with fuel to further transphobic narratives of social contagion.

Likewise, the TIME article not only provided a name for the trend of increased visibility of transgender adults and youth in America, but also made trans bodies — in particular transfeminine bodies – hypervisible in public whether or not we wished to be perceived.

In one of the first paragraphs, the cover story’s writer Katy Steinmetz established that she would “use the names, nouns and pronouns preferred by individuals, in accordance with TIME’s style.” The magazine’s style guide is not publicly available on their website to verify if this stance has remained the same, been removed, or received any added nuance to respect the fact that trans people do not simply “prefer” but instead expect to have their correct names and pronouns used.

It’s important to note that the "tipping point" sociological term is itself fraught; it was originally used to describe patterns of white homeowners leaving neighbourhoods when Black families moving in threatened their segregationist desires. Likewise, the TIME article not only provided a name for the trend of increased visibility of transgender adults and youth in America, but also made trans bodies — in particular transfeminine bodies – hypervisible in public whether or not we wished to be perceived.

In 2024, trans journalist Jude Ellison S. Doyle interviewed several experts for Xtra who criticized the level of hypervisibility the TIME article produced, and argued that the ‘trans tipping point’ has become something of a joke among trans people. Ten years later, we are subject to even more widespread hatred and legalized bigotry; if trans people have ‘tipped’ in any direction, it’s backward.”

This “tipping point” was neither the first flashpoint in journalism that brought awareness to the existence of and struggles faced by trans folks, nor a predictor of incoming shifts to achieve justice and material support for trans folks across the U.S. and Canada. In the 1950s, Christine Jorgensen accessed gender-affirming surgery in Denmark and was heralded in dozens of articles in various publications, though some, including TIME, used virulently denigrating and dehumanizing language in their coverage.

Even before Jorgensen’s recognition by Western media, youth and adults across the world were accessing hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and other transition care through a number of hospitals and clinics across America, as Johns Hopkins professor Jules Gill-Peterson exhaustively researched in her 2018 book Histories of the Transgender Child.

The mainstream journalistic narrative that gender and sexual minorities are “new” and subject to individual politicians’ and media outlets’ recognition of them in order to socially exist also has a long history. The media plays a fundamental role in portraying the struggles of marginalized people. The use of outrage journalism to increase sales and engagement at the cost of public trust and community cohesion is not new – look at the legacy of “yellow journalism” utilized by newspaper magnates Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst in the 1890s. Asserting that journalists must remain unbiased and neutral can be a smokescreen that allows publishers to advance the window of acceptable discourse in whichever political direction they wish to go. After all, it’s not possible to meet “in the middle” or compromise between factual science and fictitious disinformation: truth cannot be edited, merely manipulated.

What is at stake is not only our lived existence but also our memory – society's perceptions of us and the narratives that guide our lives and relationships.

A constant flood of op-eds attacking trans people, in particular trans women and trans youth, have effectively manufactured consent for the current wave of anti-trans hate. Numerous organizations have been created with the sole intent of discrediting trans health science, and have been repeatedly cited first in right-wing fringe media, then by more mainstream voices. Arkansas’ first gender-affirming health-care ban, passed in 2021, was arguably made possible by the doctors, journalists, and pundits who wrote these op-eds. The same goes for every single one of more than 2,000 bills introduced since 2015 that target trans people’s access to health care, bathrooms, education, and other public spaces and activities in the U.S. alone.

Into the Fire

Like many of our trans and otherwise marginalized peers, we still grieve the Nazi ransacking of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin in 1933. The destruction of its wealth of texts on trans and queer health care and other related subjects is one example of how this genocide manifests culturally. It erased whole systems of knowledge documented in the Institute’s library and destroyed irreplaceable literature and research. Some of the most recognizable and horrific photographs of book burnings during the lead-up to the Second World War show volumes pillaged from this institute being destroyed. In a way, these book burnings were a reverse tipping point – one backwards, which would take decades to recover from.

After the Holocaust, trans people seemingly disappeared from national and international headlines until Christine Jorgensen’s story emerged in the 1950s. But the Nazis could not erase the thousands, even millions, of trans people outside the reach of the Third Reich who remained closeted and undocumented.

If we are to have futures, they have to be on our terms, not theirs. If the predominantly white and cisgender-staffed mainstream media will not or cannot effectively report on the stakes of the current moment for trans people, then we will continue to do so ourselves, as we always have.

Hirschfeld died of a stroke in 1935, but his partner and colleague Li Shiu Tong continued working in sexology, documenting the prevalence of non-heterosexual and non-cisgender populations, though he received little recognition for his work before he passed away in Vancouver in 1993. One of Hirschfeld’s most well-known patients, Dora Richter, long thought to have been killed by the Nazis, actually lived on until 1966, when she died aged 74, according to archival documents unearthed by researcher Clara Hartmann only last year. There are so many archivists and researchers, trans and otherwise, who have been erased from or forgotten by the popular imagination of our various communities.

What is at stake is not only our lived existence but also our memory – society's perceptions of us and the narratives that guide our lives and relationships. The revolving door of narratives suggesting that trans identities and rights are new only serves to embolden conservatives’ dismissive and dehumanizing reactions to our existence. The documentation of violence against us is certainly not new, despite cycles of reporting that suggest otherwise.

We must also remember that access to transition has long depended on privilege. Many conservatives access safe abortions despite voting against the right to choose. Just like reproductive care, trans health care doesn’t stop happening – it just becomes less safe and accessible for marginalized people. We must reject a future in which only the financially privileged can transition; that road can only lead to a world in which no person can be openly and safely trans at all.

Trans people and other gender-marginalized groups must be able define the violence we experience on our terms. Learning from intersectional struggles – like anti-Zionist Jews rejecting broad definitions of antisemitism that divide communities and like Indigenous activists naming how European colonizers knew that enforcing their gender binary to erase Two-Spirit identities would be integral to breaking Indigenous nations’ sovereignty over their territories and knowledge – can help us resist manufactured consent for further violence.

Performative resistance, embodied nowhere better than mainstream Pride parades and their lavish corporate-sponsored facades of resistance, demonstrates the importance of telling our own stories: the very day that political tides turn against us, they give up on us. If we are to have futures, they have to be on our terms, not theirs. If the predominantly white and cisgender-staffed mainstream media will not or cannot effectively report on the stakes of the current moment for trans people, then we will continue to do so ourselves, as we always have.

Resisting violence amid apocalypse

The Nazis’ attempted elimination of trans people after the fall of the Weimar Republic happened rapidly. Within the span of mere months in 1933, trans people lost their legal documentation and ability to exist in public, transness was effectively recriminalized, and the few resources that existed were burned. Survivors fled, going into hiding and in most cases never resurfacing again during their lifetimes. With the escalation of executive orders in the U.S., a Supreme Court ruling in the U.K., and repressive legislative efforts across Canada, 2025 doesn’t look too dissimilar. Yet, even in end times, we’re still fighting and resisting. Transness will always exist. We grieve the loss of trans lives, communities, and rights, but remain hopeful that future generations will resurge. We grieve knowing that our resurgence will be under the spectre of the climate apocalypse. The comfort of believing that a strong judiciary or democracy will protect us is over, but that hasn’t stopped us from building resilience on our own.

We need journalism that documents, names, and resists violence – and not while sensationalizing it or normalizing it.

The knowledge our communities have built is being archived as we write this piece, in a distinctly modern echo of past knowledge-sharing about reproductive health care. Even if trans people are forced to go into hiding, we aren’t letting the last twenty-something years go to waste: one day, someone else will need this.

Our younger selves, even prior to coming out as trans, would never have expected to live through a repeat of watching the unfolding of Nazi Germany from across the Austrian border; we’re not looking forward to witnessing the consequences. There have already been reports of trans people taking their lives in recent months in the face of Trumpism, and numerous posts on social media detail further deaths that may have gone unreported in the mainstream news.

While the field of journalism as a whole must continue to use the term “genocide” and other ways of naming and documenting widespread violence, independent journalists, trans reporters, and other members of sexual and gender minorities have led the way in tracing the intrinsic links between our experiences of injustice and liberation and those faced by other marginalized groups.

Journalists must recognize their role. Peddling outrage for clicks, as writer Rhea Rollman points out in The Independent, perpetuates harm and distrust in an already fractured media landscape. We need journalism that documents, names, and resists violence – and not while sensationalizing it or normalizing it.

The Bell Media-owned news channel CP24 interviewed Pierre Poilievre and other members of Parliament in January ahead of the expected announcement of the 2025 federal election that spring. When CP24 asked Poilievre to speak about the issues faced by transgender Canadians, Poilievre threw back a disingenuous ‘appeal to common-sense’ response, saying he wasn’t “aware of any other genders than men and women, and found them “to be a strange priority to spend time talking about.” Through the use of softball questions with no follow up, the channel’s reporting appeared to lean into manufacturing outrage, as well as consenting to the genocidal rhetoric Poilievre used. If Conservatives form government on April 28, we doubt they will tolerate any challenges from journalists that assert the existence of our minority population, let alone any others they choose to dismiss.

We must build coalitions that prioritize collective care and the editorial independence to speak truth to the powers that be, whether that’s a Conservative or Liberal-run state or legacy media platforms which refuse to defy authoritarian bans on reporting on marginalized groups. DIY HRT has become a critical means for accessing hormones outside restrictive medical institutions, and independent outlets (such as those featured by the aggregator Unrigged) are the only publications reporting on similar grassroots efforts. Building a do-it-ourselves approach to both mutual aid and media could allow us to bypass the censorship of mainstream media and mitigate the risks that institutional medicine presents. Knowledge creation by our communities needs to be valued, perhaps even more than the apparatuses and institutions we’ve learned to depend on over the last few decades.

We must write our futures ourselves, with or without mainstream media reporting on and alignment with our efforts. We’ve done it before, and we’ll do it again on the foundation of our hope and belief that we – and not just the abstract concept of gender diversity – will survive.

This piece was produced with the generous support of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation's Media Fellowships Program.