In 2016, I was part of a Briarpatch roundtable on building and sustaining the Black liberation movement. Four years of organizing have since passed; four years of social change echoing around the world. In 2016, terms like “anti-Black racism” were still up for discussion and debate. Today, as the COVID-19 crisis and uprisings against anti-Black police brutality sweep the globe, though our language has changed, the laws and institutions that govern us have not seen radical transformation.

One example: a recent report published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives notes that Black women “face greater barriers to getting jobs, well-paid jobs in particular, compared to other racialized and white women. They are over-represented in precarious and part-time employment which typically pays less and provides fewer hours of work overall. They experience long and frequent periods of unemployment, slower career advancement, and more ‘long term’ entry-level jobs.”

Though we are undervalued, we are not without power. We are not without voice.

The already intense demands and pressures that Black women face at work have become crushing. Amid a landscape of increasingly precarious work, we’re expected to accept atrocious working conditions; act as unpaid and undervalued educators on diversity, equity, and inclusion; be attentive to the needs of our families and communities; and take the mic at protests – all while navigating pervasive anti-Black racism. We show up, but few show up for us.

Black women are at the forefront of organizing and transformation in Canada. Black women are our leading practitioners across disciplines. Though we are undervalued, we are not without power. We are not without voice.

This roundtable convened four exceptional individuals to talk about Black women’s labour. Contributors share their experiences of arming themselves against anti-Black racism at work, responding to the needs of their communities, and imagining a future that dismantles, disrupts, and complicates capitalist notions of labour.

On the roundtable

Dorla Tune has worked for over 20 years in the Canadian non-profit sector in the areas of non-profit management, philanthropy, strategic partnerships, grant writing, and community development. She holds the values of racial equity and justice central to her work. She currently lives in British Columbia on Coast Salish territories.

Sané Dube is a policy analyst and storyteller. Sané’s people are the Ndebele of what is now called Zimbabwe. She currently lives in Tkaronto/ Toronto and can be found on Twitter at @hello_sane.

Marie-Jolie Rwigema, PhD, MSW, is a researcher, scholar, and educator. She has nearly a decade of experience teaching undergraduate and graduate students at York University and the University of Toronto. She also has 20 years of community/social work experience that includes mental health counselling/therapy, arts-based education, community-based research, group facilitation, and documentary filmmaking, working primarily with Black, racialized, immigrant and 2SLGBTQ communities.

Nataleah Hunter-Young is a writer, film curator, and PhD candidate in communication and culture at Ryerson and York Universities. She has supported festival programming for the Toronto International Film Festival, the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival, and the Durban International Film Festival in South Africa. Her doctoral research explores the social and cultural impacts of social media videos documenting anti-Black police brutality and their representations in contemporary art. You can follow her on Twitter at @_Nataleah.

What does it mean to be a Black woman in Canada right now?

Dorla: Paradoxical. I have always felt a contradiction of duties, but this feeling has intensified in the past months. I feel torn between knowing I need to show up even more thoroughly in the work I do and knowing I need to retreat so that I may heal. For me, being a Black woman at this moment is knowing that no matter how tired I am, I need to roll up my sleeves and get to work because the collective Black fam is calling. At the end of the day, when the call to work comes from my brothers and sisters, the contradiction of duty disappears and this work becomes the healing.

Sané: Generally speaking, I think to be Black in Canada means constantly resisting attempts to make us invisible. There’s always a push to diminish Black presence, Black thought, Black ways of being. In the workplace, Black women are expected to be the fixer. In the last few months we’ve seen a reckoning as people take a closer look at the ways anti-Black racism harms us – but this was only ever possible because Black women have done so much work to make these harms visible. On top of that, we often play an important role in dismantling these harmful systems. I work in the non-profit sector and in that world, it is overwhelmingly Black women who are doing the taxing work of running anti-oppression training sessions, often with too little support. Black women are giving us language to talk about this moment, to understand how multiple crises are unfolding – and as often happens, their thinking and their work is being disappeared and they are not being cared for well enough.

"I feel torn between knowing I need to show up even more thoroughly in the work I do and knowing I need to retreat so that I may heal."

Marie-Jolie: The last time I was interviewed for a roundtable on being a Black woman was in 1995, when I was 12 years old and living in Vancouver. I, along with three other Black teen girls, was interviewed for the book Black Girl Talk about what Black History meant to us and what it meant to be Black Girls. One of my responses during the interview back then was this: “Being a young Black woman is the toughest thing to be because we have to put up with men and with people who are racist towards us. It’s a man’s world and a white person’s world, too. When you’re a Black person and a woman, people are always looking for some reason not to include you in something. You’ve always got to do your best to be on top. If a white person and I were going for the same job, I know they’d look for some reason to hire the white person because that happens to my mother. The people who have all the power up there are white men. But I’m going to do whatever I want to. I feel being a young Black woman makes me want to work all the harder. I want to get somewhere, and I want every other Black woman to rise above everything. People put hurdles for us to go over, and I’m going to go over them.”

I recently reread what I had said as a 12-year-old, saddened by the child who was already so clear about the misogynoir she would have to face but also proud of myself for declaring so bravely that “I’m going to do whatever I want.” Twenty-five years later, I have to say that my 12-year-old self was right. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Doing what I want will require a costly bravery. This contemporary moment for me has been about showing up bravely, despite the cost. Showing up in this way is political. Being Black in this moment means to speak the truth as I see it, when I see it, regarding racism and oppression and harm, instead of staying quiet and staying small.

"Black women are giving us language to talk about this moment, to understand how multiple crises are unfolding – and as often happens, their thinking and their work is being disappeared and they are not being cared for well enough."

Nataleah: A few weeks after lockdown restrictions eased, white/white-passing friends invited my partner and I to their home, just north of Barrie. They live a short walk away from a lake where we could (and did) float in the sun for a bit and share some distanced laughs over beers. That evening, we walked to a park and passed their elderly white neighbour en route. She waved to our small group from across the street and then said to my partner and I specifically, both Black women, “You’re a long way from home.”

That is what it means to be a Black woman in so-called Canada, now but also before: we are a long way from home. I was born and raised in Toronto, a city still home to so many people I love, have loved, and will love. But as I grow older, and travel farther by foot, plane, artwork, or book, I am reminded that I am farther away from home than I realized and, perhaps worse yet, more resigned to the realization that there can be no home for me here – even if I live here until I die.

What unseen labour do Black women take up during a time of two pandemics – COVID and anti-Black racism?

Dorla: Every day, Black women put up our invisible shields, designed to protect ourselves from the harmful impacts of anti-Blackness. We mask our inner selves – our facial expressions, our words, our actions, and our language – to protect those we care about and to protect ourselves. We distance ourselves from the daily onslaught of repetitive micro-aggressions, toxic white fragility, and the blatant acts of racism. We do not get the luxury of quarantining from white supremacy. Each day before we leave our homes, log in to our emails, or join our Zoom meetings, we anticipate what comes toward us and practise careful responses. We are constantly assessing risk.

Sané: I’ve watched Black women lead organizations and develop entirely new programs in response to the pandemic. In addition to this, they support their communities as they grieve state-sanctioned violence toward Black people. Leticia Deawuo at Black Creek Community Farm organized a food drive to ensure that Black and racialized families hit hard by the pandemic did not go hungry. She has not yet stopped doing this work. Cheryl Prescod and her team at Black Creek Community Health Centre provide an example of equitable community-led and community-informed pandemic responses, which means addressing the social determinants of health: poverty, racism, and inequality.

This work is not easy. The hours are long. The women doing this work are committed to making sure our people survive this. The ability to create programs that fully see us and see what our communities need is no small thing. Black women are carrying communities through profound moments of deep grief. Much of the labour, thinking, conceptualizing, and care for communities that Black women do goes unseen and uncelebrated.

"The ability to create programs that fully see us and see what our communities need is no small thing. Black women are carrying communities through profound moments of deep grief."

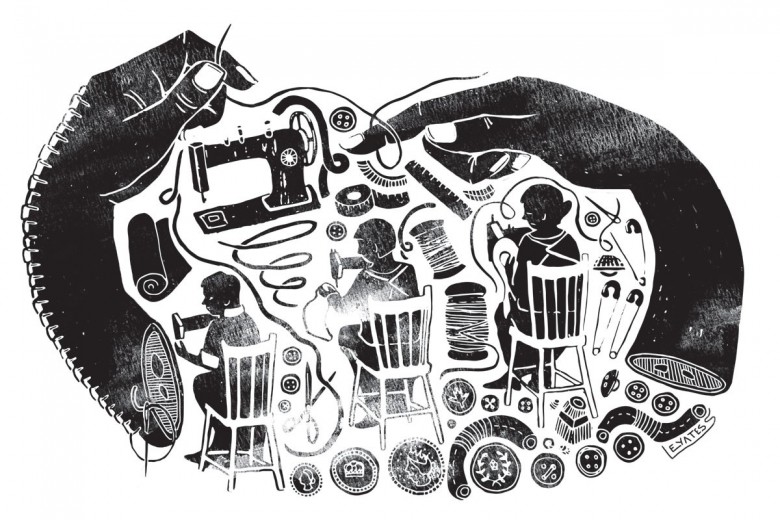

Nataleah: My partner and I spent the first few months of isolation making masks for friends, family, and colleagues. I had not touched my sewing machines for years until then. Under the adrenaline and anxiety of the unknown, and reckoning with the state of the world, it felt grounding. While others talked of newfound leisure, I laboured against a gut feeling that things would get much worse before they got better. Sewing became a tangible task that helped occupy nervous hands, tense with concern over how the emergency measures Canadian governments imposed would eventually come to further criminalize Black people and militarize our neighbourhoods. Sewing care for others into these masks was a project that attuned my mind to detail while it was mostly occupied with the weight of the world. But I couldn’t bring myself to keep sewing after police entering Regis Korchinski-Paquet’s apartment resulted in her death. I think the labour Black women do to hold grief often goes unseen.

How would you describe the experience of being a Black woman in Canada’s labour force? How do you reconcile all these parts of yourself?

Dorla: This past June, I facilitated a session for Black professionals who work in philanthropy at the Racial Equity and Justice in Philanthropy Funders Summit. A similar question was raised during this session, and the responses were: the constant navigation of white fragility and straight up racism; the burden of being the only Black person on the team; ongoing cycles of burnout; repercussions for speaking out for myself or others; being told to be patient in the face of injustices.

My main tool to reconcile these conditions is self-determination. I recently had the opportunity to consider an executive director position. A colleague said to me, “We need more women of colour in these positions.” Though grateful for the recognition, I had to remind people that this was not a role I saw as part of my career path. There were few people who asked me what I wanted. It was assumed I would jump at the chance to adopt the title and sit at a table that was not designed for me. If even in the assumption of leadership, the position denies my right to self-determination, then I am not leading. Instead, I would have done what Black people are conditioned to do: work hard in service of maintaining the racist systems that harm us each day, while Black presence is used to absolve white people of their own responsibilities in doing anti-racist work.

"If even in the assumption of leadership, the position denies my right to self-determination, then I am not leading."

Sané: I struggle often with what happens to Black women at work – the burnout, the anti-Black racism we have to endure, the misogynoir, the erasure. I know so many women who leave work because of the violence they face every day. I also think about the precarity Black women face. Early stats from COVID-19 are already showing us that women have lost more jobs and are recovering those jobs much more slowly. Anti-Black racism reminds us that even before COVID, Black women were at a disadvantage. The pandemic will exacerbate an already precarious situation. Even this conversation has too simple an analysis. I’m a Black cis woman who’s able-bodied, speaks English (one of two dominant languages in Canada), and has a graduate degree. I have significantly more privilege than trans women, women who don’t speak either of our national languages, women with disabilities, and the list goes on. Our experiences as Black women in the labour force are not the same. There is no reconciling that.

Marie-Jolie: My work has been in the social service sector and in academia. In both, there has been a huge gap between stated values and actual practices. The organizations and academic institutions I’ve worked at all pay lip service to “equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-oppression.” For the most part, many who work in the social service sector and in academia only engage with these ideas to the degree that they are useful to their personal success and career advancement. The people who compete, commodify, and hoard resources and power through the logics of capitalist accumulation tend to be rewarded and to advance more rapidly. Social service agency directors can amass a lot of funding by describing and delivering what funders want as part of a corporate model. This is often not based on the needs of people. Universities, faculties, and individual academics succeed similarly: churn out “research” that corroborates and reproduces what the ruling class likes and you will be rewarded; but attempt to do the slow, meaningful work that is truly connected to people and it’ll take too long for you to produce the necessary volume for it to be counted as valuable. @public_archive on Twitter recently wrote, “For the guiding principle for Black people in the university is this: Assimilate. Or die. Though oftentimes, both options are fulfilled simultaneously.” I’ve found this statement to be true. To the extent that I’ve been myself – a political Black Queer Woman who speaks honestly and openly and who really does believe in what she is saying – I’ve been punished in both academe and the social service sector. But it’s more important to me not to die inside.

"One of the biggest lies of a society founded in colonization and enslavement is the suggestion that, for Black people, labour is a choice."

Nataleah: At present, I labour through academe as a graduate student and the gig economy as a freelance writer and film programmer. In both realms, I am aware that I am considered both a threat to the organization I happen to be working for at any given moment (because I know things and might say them publicly) while also being one of their greatest assets for capital accumulation (the latter only inasmuch as the presence of my physical body, intellectual property, or name allows for a particular sort of highly consumable Black “authenticity”). It’s a setup. There can be no reconciliation of these parts. I am reminded each time a contract ends that I am replaceable. So I do what I can to create more space, as so many others have done for me, while also holding in sight that “inclusion” is not my goal here – change is.

What is your relationship to labour? What is Black women’s relationship to labour? How do you understand labour?

Dorla: Three themes emerge as I consider my relationship to labour: employment, mission, and birth. I often find my paid work becomes ever more at odds with my values and eventually threatens my safety as I try to fulfill my obligation of keeping my family in food, shelter, clothing, and health care. Now I find my relationship to labour in this current moment demands I reconcile my paid work with the mission. For me, the mission is the labour I do to heal and promote growth for myself, my family, and our communities. Whatever labour I do – community development, social work, consulting, writing, or reiki – as a Black woman, it is increasingly impossible to separate how I spend my hours earning money from this mission. Although anti-Black racism is not a new reality for us, what this revolutionary uprising allows Black women to do is birth a fresh way of relating to the work required, demanded of us, and, most importantly, offered by us.

Marie-Jolie: Well, my girlfriend is a birthworker, so my first thought when I hear “labour” is the labour of birthing. Labour is painful work. And it is particularly painful when we are not rewarded with a beautiful baby (in whatever form) for our labour. I think of alienated labour – work that we do that benefits the people who are exploiting us. I don’t think of care work (as in caring for people I love) and political resistance (which I think of as caring for myself – the flip side of the coin of what Audre Lorde said) as “labour,” because it births the life I want. I’ve been lucky that for the past decade or so, most of the work that I’ve done has been primarily of benefit to me and people I care about. To the degree that I can maintain that, labour has been a beautiful, often challenging, experience of building worlds that I believe in and love. Much of that has been through writing, teaching, and facilitating processes with individuals and groups of people.

Nataleah: I wonder if Black women in Canada – or anywhere, for that matter – can be seen for anything other than their labour. What are we entitled to, in this world, that we are not required to do because of white supremacy or for (racial) capitalism? My relationship to labour is simply that of requirement. I work because I have to. I have to eat, I have to pay rent. I would much rather labour in relation with others to generate wellness in community, to labour for something other than figments of property and illusions of (white) wealth, to labour for a better world. One of the biggest lies of a society founded in colonization and enslavement is the suggestion that, for Black people, labour is a choice.

What does collective struggle mean for you as a Black woman? What kinds of collective struggles are exciting and/or necessary for Black women?

Sané: When I think about collective struggle I think about that saying, “a rising tide lifts all boats.” My freedom as a cis Black woman must not take away from someone else’s freedom. If it does, then is it freedom? I think collective struggle that makes life better for the most marginalized is necessary; it actually means the world is more livable for more of us. Until Black trans women can live free and safe from violence, none of us are free. Until the undocumented Black women who have worked in health care during COVID are free, none of us are free. I also think about the collective struggle of Indigenous people and Black people. There are many places where our struggles are intertwined. Part of resisting what white supremacy does is recognizing that. Collective struggle is the only way we’ll get free.

"Until the undocumented Black women who have worked in health care during COVID are free, none of us are free."

Marie-Jolie: I just finished watching The Women of Brewster Place, the TV miniseries based on Gloria Naylor’s novel by the same name. So many of the conversations that differently positioned Black women need to have with one another actually happen in the course of the three-hour series. Conversations between middle-class and poor Black women, between queer and straight Black women, political and seemingly apolitical Black women, religious and spiritual Black women, et cetera.

Black Woman is a political identity – nothing “essential” about it. All Black women are subject to sexism and racism, regardless of the allegiances they choose later. All have had to take up oppositional consciousness to survive white supremacist heteropatriarchy at some point. They’ve also had to engage in collective struggle to survive – whether or not that struggle is overtly political/politicized or not. My mom, who was a refugee from Rwanda to Uganda to Ethiopia and eventually to Canada, does not survive without Black women in Uganda, Ethiopia, and Canada who help her and her children. I, a Canadian-raised Black and queer and gender nonconforming woman, do not survive an undergrad, a masters, a PhD, the social service sector, and academia without the (mostly) Black women in my corner every step of the way. So, the struggle is not really a choice when you live in the world we live in. The structures of society force most of us to struggle to survive. Some of us believe that we can successfully struggle and survive alone, but I’ve never seen it.