“Joan was burnt without a hand lifted on her own side to save her. The comrades she had led to victory and the enemies she had disgraced and defeated, the French king she had crowned and the English king whose crown she had kicked into the Loire, were equally glad to be rid of her.”

— George Bernard Shaw, Preface to Saint Joan

In France, Joan of Arc may be feted as a hero, but for many, the question remains whether she was simply mad. Psychiatric journals periodically publish theories about the arc of her narrative before retreating into silence once more. Was it tuberculosis in her temporal lobe? Epilepsy? Was she a highly functional schizophrenic? Or, to spite all attempts at diagnosis, was Joan instead a creative visionary destined to turn the tide in favour of the French in their Hundred Years War with the English?

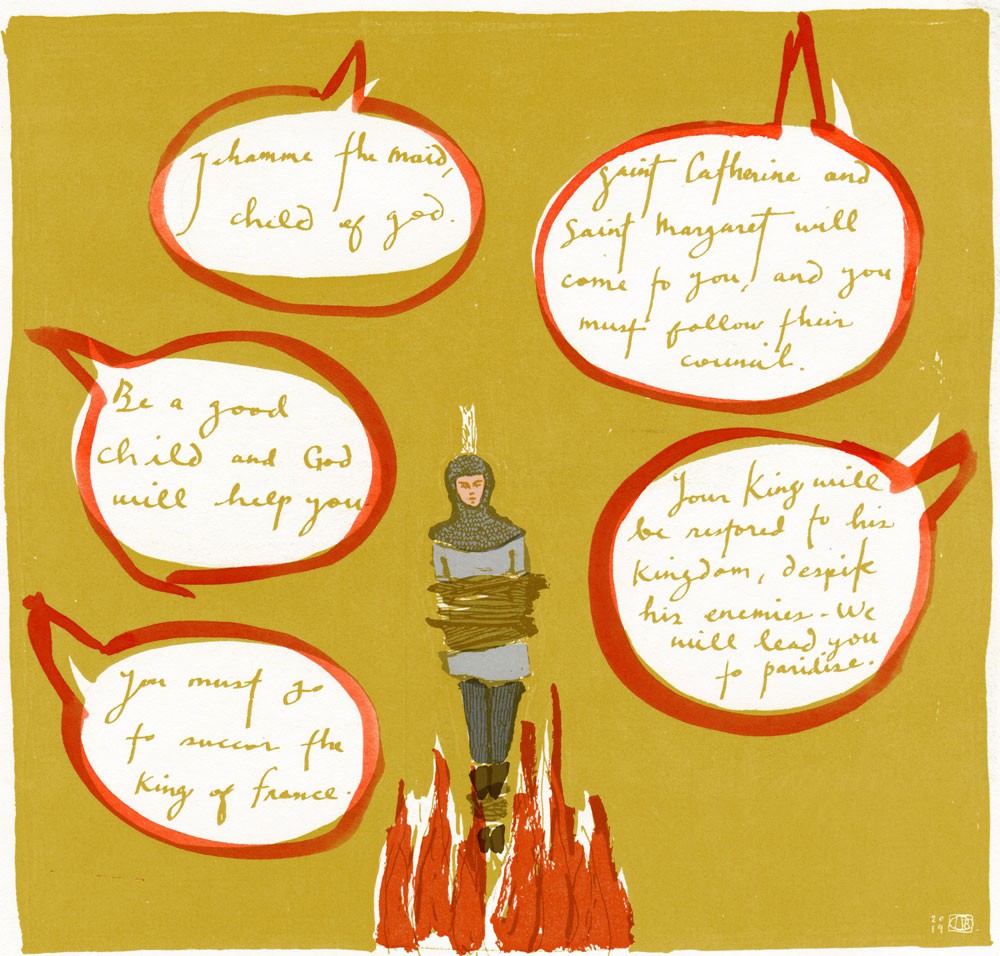

Guided by the voices of saints only she could hear, Joan was convinced her mission was divine. From the remaining scraps of history, we get only tantalizing glimpses into her psyche. The few statements we have from her offer little guidance as to what was sincere, what was bravado, and what might simply have been deranged confusion. When asked at her trial why she refused to do the work expected of women in 15th-century France, she famously retorted, “There are plenty of other women to do it.”

Railing against the normality her persecutors would hold over her head, Joan used her mission to liberate herself from society’s expectations of a small peasant girl. Psychiatrists today may fault dopamine disequilibrium, but doing so denies Joan her passionate pursuit of freedom from the limitations of her circumstances, a personal quest on which she carried along an entire nation. The French celebrated her abnormality since it served a powerful political agenda. To allies of the English, however, this improbable warrior was a menace who so profoundly threatened their dominance she had to be put to death by fire. Three times, historians note, Joan’s body was burned.

Six hundred years later, we no longer have to resort to fire. With an injection, we could silence the voices of Joan’s guiding saints, training her neurons to suppress signals from the heavens and to process those from here on earth.

Anyone who experiences six months of auditory hallucinations and delusions of religious grandeur today, along with the concomitant social dysfunction that Joan’s detractors claimed she displayed, would meet the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known commonly as the DSM) for schizophrenia, an illness that distorts perception of reality. By diagnosing and medicating her deviance, we would vanquish with ease the threat she represented.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association published the fifth iteration of the DSM, which has been the basis of psychiatric diagnosis since its inception in 1952. The manual is periodically reviewed and updated by a panel of experts, but concerns persist about its objective validity, its professed universality, and its attempt to pathologize entire ranges of the human experience that have previously been integrated into community life.

Through its five editions, the number of conditions catalogued in the tome has only grown. This expanding scope may be the result of improved observation and understanding, but like any endeavour that seeks to classify human beings, such a system allows those wielding its power to exert immense social control.

Even those involved in the development of the manual have concerns with its evolution. In response to the changes incorporated into the DSM-5, Allen Frances, who chaired the DSM-IV task force, expressed regret for his panel’s work. “Inadvertently, I think we helped to trigger three false epidemics, one for autistic disorder … another for the childhood diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and the third for the wild overdiagnosis of attention deficit disorder.”

In 2003, 7.8 per cent of American children had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In 2011, the figure had jumped to 11 per cent. Is one in 10 American children legitimately sick, or are they simply a variation of what is normal?

Debate rages. The clinical criteria for ADHD suggest it limits the functioning of children in at least two spheres of activity, such as in the home and at school, where it is most often noticed. Proponents argue that the condition has gone unrecognized, leading to generations of distressed children who could have been treated. Those more critical of the diagnosis suggest it is used to subdue children into the docile obedience required by the education system and, eventually, the labour force. No one wants a classroom or a factory full of Joans of Arc.

Critics point further to the DSM’s history as an instrument of social control. In 1957, the psychologist Evelyn Hooker stunned the field by demonstrating that gay men were no less psychologically well-adjusted than heterosexual men. In disrupting dogma, she forced experts to consider that any distress was therefore rooted in social factors, but homosexuality was not removed from the DSM until 1973. We may shake our heads now, but in 50 years, how will our treatment of people with ADHD, the other proverbial 10 per cent, be viewed when we rediscover how to engage with non-conformist learners?

A diagnosis for them all

A September afternoon. The emergency room hums with activity. The crisis worker leads me into a room where an adolescent, sporting a shaved head and wearing glasses and shapeless clothes, waits, staring at the floor.

Jim has been in and out of the hospital for months, battling depression and bouts of suicidality. His father is concerned that, now that Jim is back at school, he is being bullied for being transgender. The father seems supportive, if unable to drop his reference to Jim’s birth sex. Jim remains monosyllabic.

It makes no difference when I ask the father to leave the room. Is it school, I ask? No. Is it bullying? Naw, my friends are cool. Do you feel safe at home? Silence. Are you sad? Don’t know. Do you want to kill yourself? Shrug. Are your folks supportive? They’re trying. Are you taking meds? Yes. Are you seeing the specialist down south? Yes. Did you feel any better when you last left the hospital? No.

The entire time, Jim’s eyes do not leave his feet.

I stop, feeling stuck between exasperation and despair. What have we learned in the 50 years since Hooker’s groundbreaking work? Thirteen years old, a trans Aboriginal kid, trapped in a rough northern mining town. Clinical medicine only gives me so many tools to find him a way out. Hospitalization is temporary shelter with no guarantee of safety. No medication treats a racist, patriarchal world.

The process of psychiatric diagnosis is supposed to incorporate the social factors that influence a disease’s course. Jim might have gender dysphoria and even associated depression, but other than noting the impact that isolation and ignorance have on his condition, there is little physicians can offer to cure those ills. In the run-up to the publication of the fifth edition, the British Psychological Society restated long-standing critiques of the DSM. Its statement insisted that mental distress needs to be viewed “starting with recognition of the overwhelming evidence that it is on a spectrum with ‘normal’ experience, and that psychosocial factors such as poverty, unemployment, and trauma are the most strongly evidenced causal factors.”

Prisons provide an interesting case study for this contention. Jails worldwide house a significantly higher proportion of people with psychiatric diagnoses than the general population. In Canada, the ratio is in the range of five times. While we know people who experience social stressors – such as extreme poverty and colonial oppression – are more likely to end up in the corrections system, the causal link with mental illness is less evident. Is it an independent factor for incarceration, or do social stressors contribute to mental distress, which leads to entanglement with the judicial system? We know that prison itself aggravates psychiatric conditions. The DSM might depict a world populated by sick people, but what if it is instead the world that is sickening for many who live in it?

The paradigm of psychiatry atomizes the experience of distress, making it an individual issue for which the collective bears no responsibility. Through diagnosis, we devolve responsibility for dysfunction onto the patient rather than holding accountable the structures that make people feel sad or crazy. Jim’s depression is only one example. There are immigrant parents driven to suicidality, unable to keep up with the rent, women who hear voices saying they are the root of all evil in the world, young veterans who lash out in rage at the slightest sound reminiscent of the battlefield. The DSM provides a diagnosis for them all. But does it lead us to a cure?

Permission to grow old

Tom is a retired mining geologist, widowed 10 years ago. For eight months, he has been to the clinic with distressing regularity, concerned about his blood pressure. I have learned that repeat visits mean that someone is not asking the right question, that the problem stated is not really the problem at all. Tom’s blood pressure is probably the least of his worries.

I am new at the clinic, so I have the luxury of professed ignorance. I ask questions, probing fears, picking at worries, poking at despair. When Tom begins to cry about his dog who died, I realize I can stop. His son, who has been towering over his stooped but dignified elderly father, hisses, “Dad, it’s been two years!” But what do two years mean when the loss of his dog spelled the end of their rambling walks together, another sign that all the moorings to which he once attached his life are gone and that he too will soon be helplessly adrift? A spike in blood pressure makes him think he is about to have a stroke, which fills him with dread at his looming dependency.

I hesitate as Tom wipes his tears. In my mental checklist, he meets the DSM criteria for depression. But is it so much depression as it is the human condition? Do I offer medication when poets and philosophers have addressed his fears with as much – or perhaps as little – success as physicians?

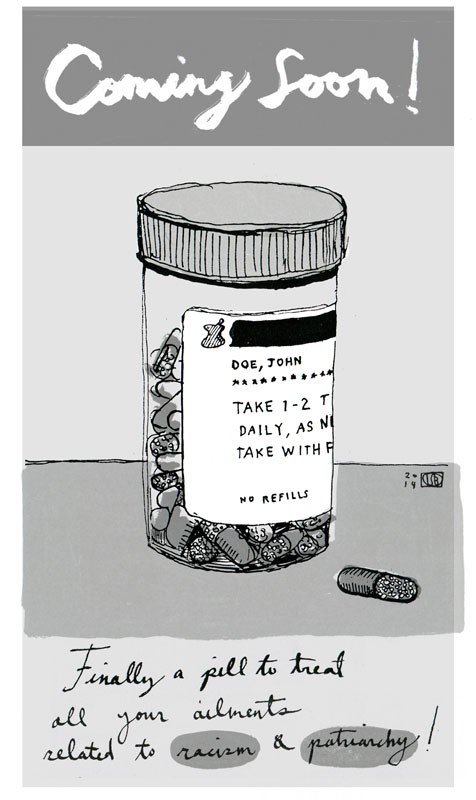

Using the DSM to identify illness is only useful if there is an intervention to offer. In isolating a condition for treatment, we also silence the uncomfortable questions the condition asks us. The rise of psychoactive pharmacology has profoundly shaped our approach to mental health: it has been the root cause of a more comfortable, reductionist, biochemical approach to the human psyche. But the introduction of a profit motive – the ability to sell a cure for abnormality – has shaped it even more. When members of the DSM-5 panel were initially asked to sign a nondisclosure agreement, there was vociferous opposition to this confidentiality clause, rooted in concerns about conflicts of interest.

Robert Spitzer, who led the development of the DSM-III, said: “Transparency is necessary if the document is to have credibility, and, in time, you’re going to have people complaining all over the place that they didn’t have the opportunity to challenge anything.” When nondisclosure was finally revoked, two-thirds of the DSM-5 panel declared direct ties to the pharmaceutical industry, a significantly higher proportion than previous DSM panels.

The DSM-5 panel’s expansion of diagnostic criteria means that one in 20 menstruating women now meet the criteria of a psychiatric disorder. Mood changes during the luteal phase of the cycle that have existed for millennia are suddenly a mental illness worthy of pharmacological treatment. The diagnosis of anxiety used to require that patients themselves recognize that a debilitating worry was in fact irrational. The DSM-5 abolishes this requirement for self-awareness, allowing clinicians to decide whether someone’s fear is truly warranted or not. The expanded scope has even encroached on bereavement, where the two-month grace period to mourn in the DSM-IV has been collapsed to two weeks before physicians can diagnose depression and thus prescribe antidepressants (a $10-billion industry in the United States alone).

Though universal, grief manifests itself in profoundly personal ways. Tom was not simply mourning his dog, but mourning a life well-lived, struggling to come to terms with mortality. Although the DSM dictated to me that he was ill, I could not bring myself to suggest that he pay for medical permission to grow old. “Maybe you can come back next week and we can chat some more … without your son,” I tell him instead. He looks at me and nods, even smiling through his tears.

Social demons

For some, psychiatric diagnosis has been liberatory. The biological framework and the categories that arise from it have given people ways to understand their alienation, to understand why their reality jars with that of others. It has defused moralizing about those with addictions, and it has encouraged us to think about the diversity of ways in which people may interact with their social and emotional environments. Diagnosis has meant access to resources that were otherwise denied to some people.

Pharmacological treatment, especially if embedded in regimens that include social and psychological support, has transformed many lives. But people are not simply their biology, and biological determinism has its limits. We refuse to believe people can be explained simply by their sexual hormones, so what of their neurotransmitters? We contest the medicalization of birth, at hospitals instead of home, by procedure instead of patience. Why then push sadness or spirituality into the domain of medicine as well?

In medieval France, when alternate realities became inconvenient, they used fire. Today, perhaps thankfully, I reach for my prescription pad. But as a physician who has wavering faith in the potions I push, I struggle with the discipline of psychiatry. My colleagues approach their patients with the best intentions. But our contemporary paradigm emerges from a particular economic and political context, buttressed by powerful interests for control and profit.

A society celebrates or suppresses parts of the human psyche according to the demands of its own demons. We act now with the utmost faith that we have science and morality on our side, appalled at the way those who deviate from the norm have been treated by the barbarisms of the past. But who is to say that when we are studied from afar we shall not be similarly judged?