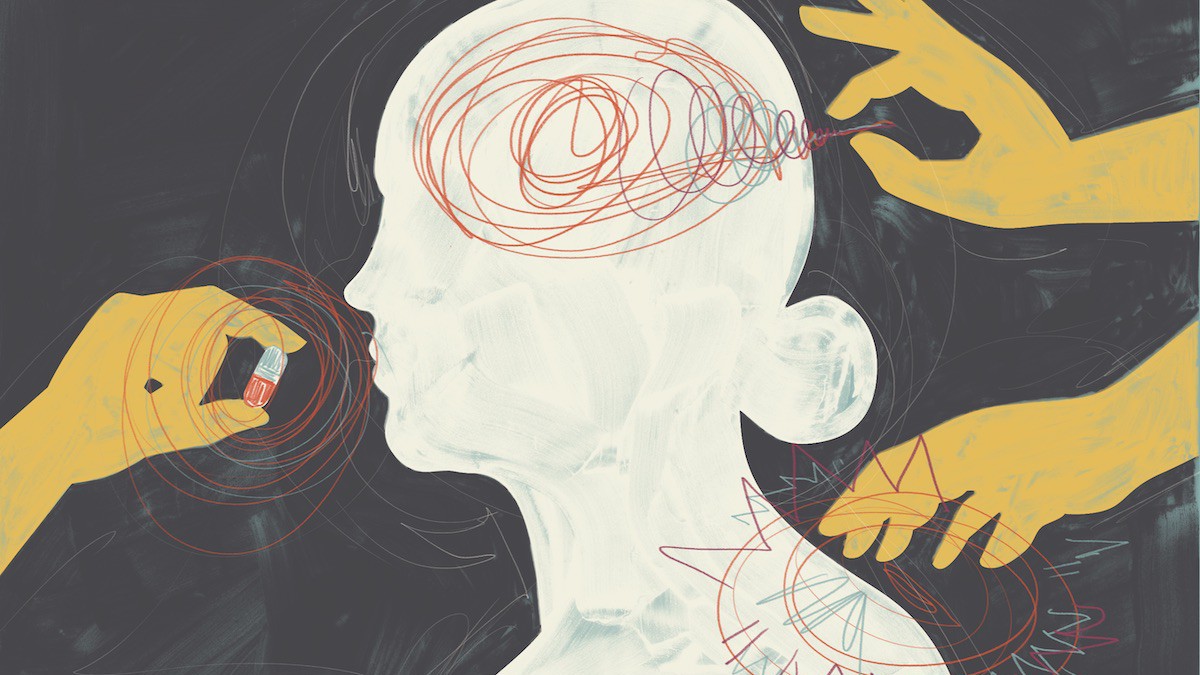

Of the 20 per cent of Canadians who have a mental illness and who are taking medication, most will, at times, forget to take it. According to some people, this is not just a health issue but an economic problem, said to cost the Canadian government billions of dollars yearly in additional health-care costs. What better way to resolve these adherence issues – and cut these costs – than to put a digital tracker in the body of the client/patient?

The idea may seem dystopian, but it is already being pursued. In 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved one of the world’s first digital pills: Abilify MyCite, an antipsychotic usually prescribed to people living with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. People with these mental illnesses have been found to be non-adherent, meaning they’re particularly likely to forget to take (or likely to stop taking) their prescribed medication, and MyCite promises to help “you and your healthcare team stay on top of how your treatment is going.”

For people living with a mental illness who are also criminalized, this technology could have serious carceral implications, threatening to make surveillance and control by doctors and prison guards even worse.

Here’s how it works: when the pill comes into contact with the stomach acids of the drug taker, it triggers a digital time stamp. This activates a Bluetooth-enabled wearable sensor patch on the body of the drug taker, which then sends information about the pill consumption an app on a smartphone. MyCite not only tracks whether it has been ingested, but also automatically logs the consumer’s physical activity and time spent resting, and allows the consumer to input their mood and the reason they didn’t take the pill – all of which are “conveniently” uploaded to the cloud.

Anyone nervous about this sweeping collection of intimate, personal information might ask, “Who is tracking this data?” According to the pill’s creator, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc., the data would likely be sent to a physician who can make sure that a patient is following their drug plan. “The people you choose to share your information with will be able to access your data on the MyCite Dashboard, allowing them to quickly check in and see how you’re doing,” MyCite’s website explains.

But doctors are not the only ones monitoring people’s medications, and not everyone has the freedom to decide who observes their treatment plan. For people living with a mental illness who are also criminalized, this technology could have serious carceral implications, threatening to make surveillance and control by doctors and prison guards even worse.

Psychiatric incarceration

While digital medications like MyCite are not yet readily available in Canada, their forerunners – medication tracking systems – are already being implemented here. For example, PrescribeIT is an e-prescribing service in Canada that allows clinicians to monitor if and when clients’/patients’ prescriptions have been dispensed by a pharmacy. When digital pills become available, they will add to the list of technologies used to surveil some of the most vulnerable and marginalized people in society, such as people who experience psychiatric issues and who have also come into contact with the criminal-legal system.

Mental illness rates are about four to seven times higher in prisons than outside of them, with 30.4 per cent of prisoners having an active psychotropic medication prescription; for women in particular, the number rises to 45.7 per cent. A psychotropic can be an antipsychotic or an antidepressant – but both can produce sedative effects, and there’s evidence that both types of drugs have been overprescribed in Canada’s prisons. For example, a joint CBC News/Canadian Press investigation revealed that until 2011 an antipsychotic drug called quetiapine (brand name Seroquel) was being prescribed off-label to prisoners as a sleep aid, even though it was only approved for treating bipolar diseases and schizophrenia. Seroquel has side effects that can be lethal, even when it’s used correctly.

“The one thing with prison is that they like to heavily medicate people, and I’m a prime example.… Seroquel, stuff like that. I was on a lot of medications. I was a walking zombie. I could not function. I do not remember half of my time.”

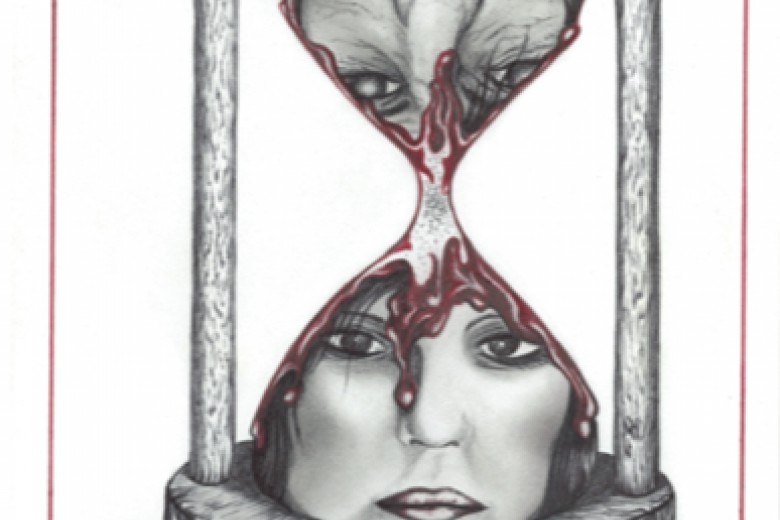

As more and more people are incarcerated each year in increasingly horrifying conditions, antipsychotic pills and other psychotropic medication can serve as a “techno-correctional” policy for keeping prisoners docile. In his book Tranquil Prisons, disability scholar Erick Fabris proposes that such drugs have been used as a “chemical straitjacket,” meant to subdue and pacify prisoners to make them more “manageable.” During a 2008 University of Ottawa study on Seroquel in women’s prisons and jails, one participant told researchers, “The one thing with prison is that they like to heavily medicate people, and I’m a prime example.… Seroquel, stuff like that. I was on a lot of medications. I was a walking zombie. I could not function. I do not remember half of my time.”

While most prisoners experience insufficient health care once in prison, many (especially racialized prisoners and women prisoners) may also be medicalized. Medicalization is a colonial social process where non-medical issues are identified and treated as medical ones – for example, someone resisting arrest may be labelled as having oppositional defiant disorder and be medicated with an antipsychotic.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with treating mental illnesses as medical issues and providing prisoners with therapy and drugs so that they suffer no additional harm. But drug treatment can easily fall under the umbrella of medicalization when it’s motivated by a desire to control behaviours rather than alleviate symptoms. For example, a prisoner who is having extreme nightmares due to their experiences of violence may be medicated – not to stop them from having nightmares, but instead to stop them from shouting in the night.

The medicalization of prisoners can also take attention and resources away from addressing the social issues, like poverty, that lead to mental health challenges. Instead, medicalization (like incarceration) places the responsibility on the individual prisoner, absolving governments from their responsibility to address the underlying structural social issues. For example, Indigenous women are particularly likely to be labelled with a mental illness while incarcerated – a result of the combined impacts of colonialism, racism, sexism, and ableism on Indigenous women both outside of and inside prisons.

Surveillance (of) pills

Informed consent and choice are integral to treatment plans. While people who have been psychiatrized and/or criminalized may choose treatment in consultation with a doctor, often the state will impose medicine with the goal of “helping the patient recover.” Often such clients/patients are forced to take an antipsychotic to limit hallucinations and “bizarre” behaviours. Clients and patients who experience what doctors call “psychoses” are often denied the ability to choose their own treatment after being labelled as “lacking insight” or “legally incompetent or incapable” to make decisions about their medication. Herein lies the utility of drugs such as Abilify MyCite, which ensure that “incompetent” and “untrustworthy” clients/patients take their medication and are tracked by a psychologist or psychiatrist.

When a person is involuntarily committed to psychiatric institutions because they are “likely to cause harm,” “suffer substantial mental or physical deterioration,” or are “not capable of making an admission or treatment decision,” they may be brought before a judge or to the hospital by the police for a committal decision. The rules and criteria for this process vary slightly by province or territory. For example, the Mental Health Act of British Columbia states that after someone is involuntarily admitted to a hospital, they are deemed to have consented to any psychiatric treatment prescribed by the physician. This includes medication, both while they’re being held at the hospital and when they are released on extended leave.

For example, a prisoner who is having extreme nightmares due to their experiences of violence may be medicated – not to stop them from having nightmares, but instead to stop them from shouting in the night.

In Canada, such compelled treatment can also be enforced outside of hospitals and prisons through community treatment orders (CTOs) that mandate people to take drugs on release from incarceration or else risk reinstitutionalization. Police can be called to enforce CTOs and force people back into hospital or prison. In Tranquil Prisons, Fabris writes that CTOs are initiated by a clinician in Canada (as opposed to court ordered, as they are in the United States) and are aimed to stop the “revolving door between hospitals and prisons.” In this way, CTOs are essentially legally ratified medical coercion. Though CTOs and pills like MyCite may seem preferable to incarceration, they actually extend the logic of incarceration outside the prison: to subdue, control, and surveil people who are deemed incompetent and dangerous.

Institutionalized and psychiatrized people who are reintegrated into the community after being incarcerated (either in hospital, jail, or prison) are often expected to follow a strict medical treatment program, which at times includes being injected with long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAI). LAIs have been found to limit hospital readmittance but they do not come with the biofeedback markers (like sleep or activity) that Abilify MyCite provides. With the advent of pills such as Abilify MyCite, such forced drugging can also serve as electronic surveillance, akin to an ankle monitor.

For people who already have their medication tracked within the criminal-legal and psychiatric systems, digital medical systems like MyCite would strip away the morsel of agency that is choosing to take one’s meds. When “treatment” comes with coercion and restraints, social and health outcomes tend to be quite poor, because of the distress caused to the person being “treated.”

Though CTOs and pills like MyCite may seem preferable to incarceration, they actually extend the logic of incarceration outside the prison: to subdue, control, and surveil people who are deemed incompetent and dangerous.

While MyCite is not yet legal in Canada, the pandemic has funnelled attention and money toward the Canadian digital health space; Canada-based digital health start-ups raised more than US$300 million in 2020 alone (double what was raised in 2019). Canadian privacy experts are anticipating that digital identification projects long in the works will start to go live in 2021 – including digital health cards and technologies that would offer digital proof that a verified person is allowed to access a health care account. Considering that medication non-adherence costs governments money, it’s not surprising that we’re also seeing a coordinated effort between provinces, Health Canada, and Canada Health Infoway to implement e-prescribing at a national level. That is, there is a push to expand data collection and sharing in order to close “information gaps” on Canadians’ prescription information.

It’s not hard to see that – like digital ID and e-prescribing – a pill like MyCite would garner a lot of interest from policy-makers and Correctional Service Canada. It is important to refuse the steady creep of carceral technologies into every facet of our lives and to limit the negative impacts of such technologies on the lives of psychiatrized and criminalized people.