Plain language summary (What is this?)

- Meals in prisons, nursing homes, and hospitals taste awful. The terrible meals are made by the same large companies and are usually frozen and then reheated before being served.

- There are many similarities between how people in prisons, nursing homes, and hospitals are treated.

- Three people who live or lived in prisons and nursing homes share about their food experiences inside. Here’s what they said:

- In prison: “This meal was not edible in my eyes, and I would usually trade it away for a small single-use Jif peanut butter package.”

- In a nursing home: “I’m forced to rely on this food. It’s crap that I can’t even pick what I eat, especially when I could at my last facility.”

- In another nursing home: “The food is not what I would call good. I will eat it and not vomit, but I don’t get any joy.”

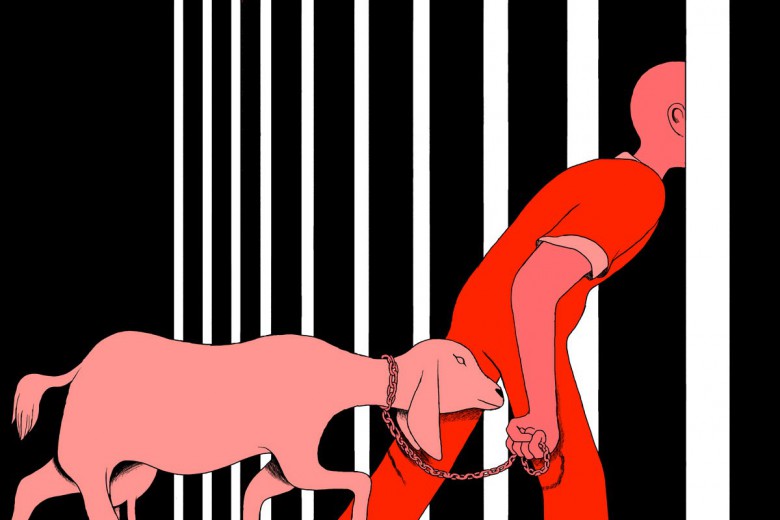

I’ve spent a lot of time in the hospital eating lukewarm foods that do little to mask the terrible taste of drugs. There’s a special solidarity in breaking the stalest of bread with your hospital roommates. We share this bad food not just with each other, but with our institutionalized and incarcerated kin in nursing homes and prisons.

Abolitionist and disability justice scholar Liat Ben-Moshe understands prisons, nursing homes, and hospitals as points along a continuum of confinement. At their core, these institutions seek to remove and isolate people from their communities under the guise of rehabilitation and support.

Institutions – whether they’re run by a corporation or a government – are focused on keeping costs down by any means necessary. When institutions for disabled people and prisons were established, their massive grounds often included farms, designed to make each institution wholly self-sufficient and isolated from society. These farms relied on the unpaid labour of inmates to harvest and cook food for other inmates. After the introduction of neoliberalism, governments found a new way to cut their costs in prisons and institutions for disabled people: outsourcing food provision to private companies.

Today, multinational corporations like Aramark and the Compass Group Canada are responsible for food provision in hospitals, nursing homes, and prisons across the world, raking in billions in revenue each year and serving similarly disgusting food at each. Aramark, for example, provides food for the long-term care institution Martha’s House in Alberta as well as the canteen services for federal and provincial prisons. Over the years the company has come under fire for a spate of different offenses: it’s served maggot-infested food and rancid chicken to U.S. prisoners; it’s stolen wages from its workers in California and Boston; and it’s been fined for not keeping enough food on hand to feed prisoners.

To understand what life is like along the continuum of confinement, three people living in prisons and long-term care homes share about the food they have eaten and eat every day.

Food at the Deer Lodge Centre long-term care facility in Winnipeg. Photo by Shoshana Forester Smith._sandwich_1000_1333_90.jpg)

Toronto South Detention Centre

Name: Anonymous

Facility: Toronto South Detention Centre (The South)

Bio: Anonymous is a Métis and Cree prisoner turned prison abolitionist. He’s hopeful that change will come in the future so that others can see people inside as more than people in orange.The meal was faux ham circles and scalloped potatoes with a side of unknown sour sauce and stalks of mixed vegetables. Due to COVID-19 precautions, it came in a cardboard tray with three sections instead of the normal plastic reusable ones.

These trays were smaller than a Hungry-Man TV dinner and never seemed to contain enough food. Even though they were made of cardboard, the trays were not recycled – every day, three of these trays per prisoner piled up in our garbage and landfills. This meal was not edible in my eyes, and I would usually trade it away for a small single-use Jif peanut butter package.

To eat meals like this every day feels degrading. We can’t get a list of ingredients, we can’t know where the meat or food came from, and we can’t find out its nutrient content without paying for a $600 freedom of information request.

Bread and biscuits are touched by the guards and placed into individual brown bags for every inmate. These guards wear latex gloves while handling our food – the same ones they use to touch cell keys and many other unsanitary surfaces – and then they shrug it off like it means nothing. They often stuff these brown bags with milk and juice bags that either soak or squish the bread, and we are just expected to take it or leave it. It feels like we are fed the same way caged animals are.

The Toronto South Detention Centre is fully equipped with a kitchen to feed its population fresh food – but still decides to outsource food provision to another company. All our food is made at the Maplehurst Correctional Complex in Milton and then frozen and shipped to the South.

The company contracted to provide food at the South is Eurest, a subsidiary of the Compass Group Canada, a massive food distributor to prisons, hospitals, and long-term care facilities. It raked in $17.9 billion in revenue in 2021, paying its CEO $7.2 million in 2019.

Amid these profits, food shortages remain common in institutions. In 2020, incarcerated people in Ontario prisons organized hunger strikes, rejecting the frozen meals and decrying small food portions and mouldy or expired canteen items.

Alongside their provision of food inside prisons, subsidiaries of the Compass Group Canada, such as Marquise Hospitality, are contracted out to long-term care facilities and hospitals across Canada. The food in long-term care facilities is a frequent complaint – from January 2018 to May 2019, long-term care homes in Ontario saw 660 formal reports of food and nutrition issues, which included missed meals, stomach flu outbreaks, and residents choking.

Food at the Deer Lodge Centre long-term care facility in Winnipeg. Photo by Shoshana Forester Smith._eggs_1000_1333_90.jpeg)

Deer Lodge Centre long-term care facility

Name: Shoshana Forester Smith

Facility: Deer Lodge Centre long-term care facility, Winnipeg

Bio: Shoshana Forester Smith is a Saulteaux Ojibwe Reform Jew based in Treaty 1 Territory and a patient advocate.The grilled cheese is not even grilled. No margarine or butter on the bread. It’s dried out bread (they toast it hours before serving it) and melted cheese. It’s disgusting. The scrambled eggs also fall victim to dryness. They are petrified and inedible. They are as if you put them in a food dehydrator. Absolutely disgusting.

What we get is food that is never the right temperature and is often dried out or soggy. Hot food is cold and cold food is lukewarm. The containers they use for hot food cause condensation to pool and it makes the food damp.

In Winnipeg, most of the hospitals get their food from a central repository called the RDF (Regional Distribution Facility – doesn’t it sound yummy?) where all the meals are pre-made hours before they will be served. The meals are trucked to the facilities where they are put in “re-thermalization units” (that don’t work well) where cold stuff is supposed to stay cold and hot stuff, hot.

I’m a kosher vegetarian who is also Indigenous, and getting food that is culturally appropriate is tiring and not always possible. Thank goodness my meals are supplemented with total parenteral nutrition or I would starve to death here. I get a lot of the same things all the time, such as egg salad sandwiches. Seriously, some days I get them for both lunch and dinner.

Meals are served in our rooms, so early. Who wants dinner at 4:30 p.m.? Trays are not collected afterward, so I’m relegated to staring at gross food for hours.

Nutrition is so important and such a quality-of-life thing, and especially since I can’t keep a fridge in my room, I’m forced to rely on this food. It’s crap that I can’t even pick what I eat, especially when I could at my last facility. I moved here because my last facility was not able to provide the medical services I needed. But here, I have lost the ability to make any choices, even though the food is prepared at the exact same facility.

I don’t think it’s a huge ask to choose my meals. They also need to provide us with more food for snacks. It’s toast or cookies – that’s it. Sorry, and juice. But I don’t count juice as a snack.

Food is a fundamental part of cultural and spiritual identity and practice. During the holy month of Ramadan, many Muslims fast from dawn to sunset – but in Canada, Muslim inmates have spoken up about how prison restrictions prevent them from fasting – they’re not let out of their cells to eat until after sunup, not served large enough meals to sustain them during fasting hours, and not given access to washrooms after sundown. Jason Cain, a Muslim prisoner in the Donnacona prison in Quebec, told Global News, “God’s looking down, he realizes that this is not my fault, but at the same time, you feel kind of guilty because you’re not able to fulfil your religious requirements [and] you feel like you should be strong enough to.”

Food is another way that prisons and long-term care institutions dehumanize people and isolate them from their communities.

Food at the Arborstone Enhanced Care nursing home in Halifax. Photo by Vicky Levack._meal_1000_1333_90.jpeg)

Arborstone Enhanced Care nursing home

Name: Vicky Levack

Facility: Arborstone Enhanced Care Nursing Home, Halifax

Bio: Vicky Levack is a Halifax-based disability and housing activist and spokesperson for the Disability Rights Coalition. She is currently institutionalized in a long-term care facility. In 2021, after years of advocacy, Levack won the right to live independently and receive at-home care from a support worker. Her release is pending.It will not make you die; it fulfills its purpose.

The meal today was watery and flavourless shepherd’s pie with unknown meat. Normally, potatoes are served with this meal. But I have a vendetta against mashed potatoes and I refuse to eat them, because we get them every single day. This meal came on a plastic plate that made the unknown meat juices infect all the vegetables. I used to be a lacto-ovo-vegetarian (a vegetarian who eats dairy and eggs), but I can’t be here. The spinach is flavourless and wet, like most of the vegetables.

Growing up, I never understood how people could dislike vegetables. But now that I live here, I hate them. In the nursing home, vegetables are mushy and flavourless – somehow always similar to baby food (I can say that; I’ve had to eat baby food on many occasions).

While I’ve never had to go a day without food, the food is not what I would call good. I will eat it and not vomit, but I don’t get any joy. It doesn’t make me feel anything other than that I am incarcerated. And while I’ve never been to prison, it makes me think about it. Simply put, the food I’m given is a substance to keep me alive so my body can function.

It’s either it tastes good and it’s terrible for you, or it tastes terrible and is terrible for you. The portion sizes are so small that I’m often still hungry after a meal. They try to make it appetizing, but they don’t have a lot to work with – health-care workers will present it and say “I’m sorry.” Other times, you ask them what it is and they say, “I don’t know.”

Prisons, hospitals, and nursing homes claim to care for and rehabilitate the people trapped inside them – but they can’t even provide one of the most basic requirements for dignity: good food. It’s not an accident but a feature: as long as there is money to be made and power to be accrued from confining some people, bad food will persist in institutions. Simply changing the food will not result in freedom or autonomy for the people inside.

Those who call for the abolition of prisons and long-term care homes know that the only way to remedy the disgusting food in institutions is to “grab the root” of the cause of ongoing confinement: the idea that society is better off when certain people are locked up. Instead, abolitionists recognize that there is another way to care for people, free of incarceration and confinement. We can build strong and supportive communities where we keep each other safe – complete with delicious meals, rooted in food sovereignty and always with enough to share.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)