When Gladys Radek set out on her fifth cross-Canada walk this past summer, she couldn’t help noticing the saplings lining the maritime stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway. To Radek, the saplings looked like little crosses, each marking a lost life. Trekking west from Halifax to Prince Rupert, she eventually reached northern B.C. where this story originates. Radek was once again on the Highway of Tears, the stretch of Highway 16 where between 18 and 43 Indigenous women have gone missing. There, beneath the pounding sun, the roadside saplings seemed to flag. In those little trees, Radek felt the heartbreak of those linked to a missing or murdered Indigenous woman.

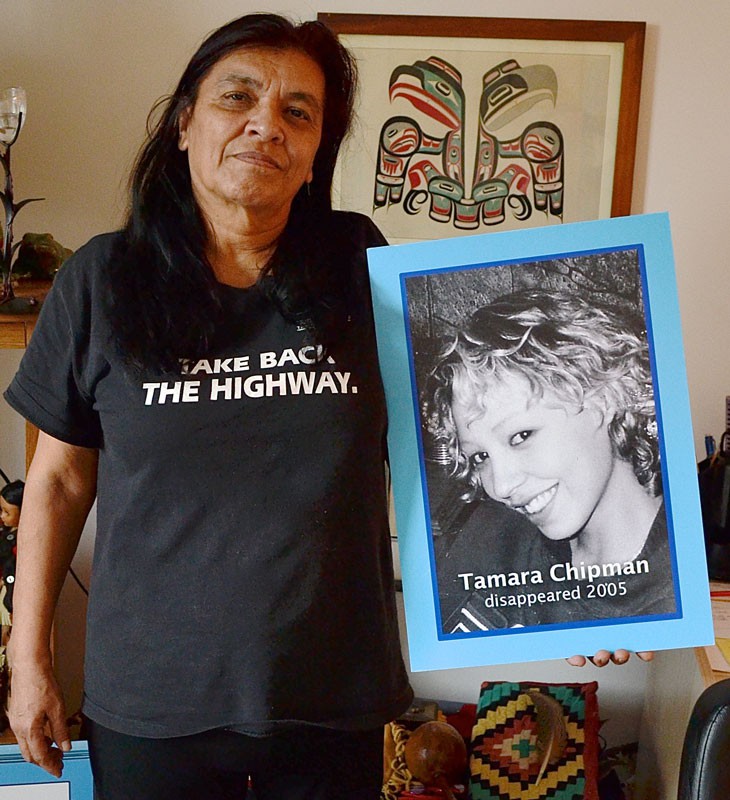

It took three months, but the walkers arrived at their final destination to the sound of drums and the smell of a feast welcoming them. They arrived exactly eight years to the day that Radek had received the chilling phone call that would be the catalyst for her cross-country treks. On September 21, 2005, she was informed that her 22-year-old niece Tamara Chipman had gone missing on Highway 16.

“I had heard my families talking about missing loved ones, but growing up with that and knowing this was actually happening didn’t really click for me until Tamara,” says Radek. Growing up in a flawed foster care system in Moricetown, B.C., and later living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, Radek was well acquainted with the trauma and abuse of Canada’s colonial realities. For years, she had already been a champion of the rights of Indigenous women, fighting for justice and accountability though grassroots initiatives.

But by 2008, with no news and little support from authorities about her niece’s case, Radek felt she had to do more to raise awareness about the approximately 600 missing or murdered Indigenous women in Canada. So she co-founded the Walk4Justice. The walks bring attention to the issue – which Radek feels is more severe than the RCMP will acknowledge – with an emphasis on the devastating stretch of highway between Prince George and Prince Rupert.

“When you’re walking on the highway, you feel the spirits of those women,” says Radek. The latest walk, Tears4Justice, was focused on uniting the families and reminding them that they are not alone. Throughout the walk, Radek was met by family members of missing women, some for a few hours and some for a few days, all gathered by word of mouth.

The treks are not easy for any of the walkers, but they’re particularly challenging for Radek. As an amputee who lost her left leg in a hit-and-run motorcycle accident the day before she turned 18, these journeys for justice exact a physical as well as an emotional toll. “The blisters that I got on my leg were always nursed by the other walkers, and they were nothing compared to the hole in my brother’s heart, missing Tamara,” she says.

The hardest elements for Radek on her most recent trek were hearing from new families with missing loved ones and reconnecting with past families who have seen little justice or change over the years. Radek is in constant correspondence with her contacts, attending rallies with fellow activists and spreading awareness through social media, stressing that “we can’t be scared to speak our truth.” Her voice is not her only tool: Radek has covered her white GMC van with the faces of missing women. Her War Pony, as she calls it, raises awareness everywhere she goes.

As for what’s next, Radek is putting to paper the ideas affected families have discussed for a national action plan. She will work with her supporters across Canada to push for the public inquiry thus far refused by the federal government. When asked if she still intends to take her work to the United Nations, Radek says: “You’re darn right. I’m going to be a women’s activist until the day I die.”