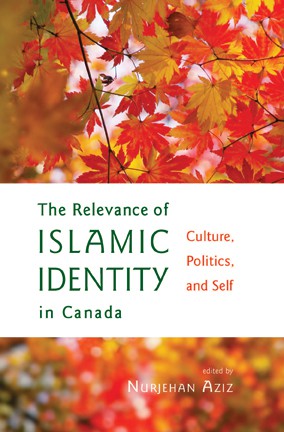

The Relevance of Islamic Identity in Canada: Culture, Politics, and Self

Edited by Nurjehan Aziz

Mawenzi House, 2015

The “Muslim issue” at the heart of the 42nd Canadian federal election was but one sign that Islamic identity, politically and culturally, is relevant to many Canadians. In the lead-up to the election, the anti-terrorism legislation in Bill C-51 prompted rallies across the country. The Harper government’s reluctance to open up Canadian borders to Syrian refugees sent social media into a #RefugeesWelcome frenzy. The niqab, deemed by then-prime minister Stephen Harper as “rooted in a culture that is anti-woman” and “not the way we do things here,” became the Conservative Party’s final fear-mongering attempt to win another election. Though much credit for the Liberals’ electoral triumph was given to their “we beat fear with hope” narrative, the question of what it means to be Muslim in Canada continues to be relevant – not least for Muslims themselves. This is the question 11 writers grapple with in their contributions to Mawenzi House’s The Relevance of Islamic Identity in Canada: Culture, Politics, and Self, edited by Nurjehan Aziz.

The anthology aims to present diverse perspectives on Muslim identity in Canada from community organizers, artists, novelists, and academics. A publication that features multiple Muslim voices writing about their identity is an incredibly important project and opportunity to challenge the framing of Muslims as a homogeneous group that is violent, backward, and inherently incompatible with Western culture. The anthology attempts to take on this project through a mixed collection that includes both personal narratives and analytical, research-based essays.

Those pieces in the collection that are personal narratives are penned by secular writers who explore the challenges Muslims face when religion is politicized. As Ameen Merchant puts it, “my sense of Muslim identity may not be another’s definition of what a Muslim ought to be and it also may not be in line with scripture and sacred text […] but I am also not just a Muslim.”

The personal narratives of secularity range from Merchant’s rejection of Islam as his religious identity to Safia Fazlul’s concern with cultural Islam in the Bangladeshi diaspora, and Asma Sayed’s description of family dynamics that bridge her family’s identity as “Shia, Sunni, agnostic and secular” with her own. These personal narratives unpack the many experiences of being Muslim and dispel perceptions of the commun-ity’s homogeneity.

The research-based essays are written by self-identified practising Muslims such as Amira El-Ghawaby and Monia Mazigh. They explore political issues such as the shaping of municipal space with the presence of mosques, the ongoing examination of gender relations within Islam, and the politicization of Muslim identity throughout the Harper decade.

Coupling secularity with personal narratives versus faith with detached analysis inadvertently perpetuates a problematic pattern of assumptions. Those writers in the anthology who don’t congregate in mosques, who celebrate Christmas with their families, who don’t wear the hijab are not the imagined threats to their Islamophobic neighbours. By dividing the storytelling this way, the warmth and complexity of personal stories is reserved for secular Muslims, while practising Muslims’ contributions are the more removed, cerebral analysis – the relatable complexities of personal stories are left out.

The absence of personal experiences of Muslims in Canada who have a deep concern for Islam as their chosen religious identity situates the anthology as perpetuating the “good Muslim–bad Muslim” dichotomy. “Good Muslims” are those who opt out of wearing veils or growing beards, who perform whiteness through their occupations, interests, and participation in normalized social activities. “Bad Muslims” are those who take breaks at work to pray, speak with accents, are racialized, build mosques, and create community among themselves. This dichotomy is emphasized when “progressive” and “integrated” Muslim voices are invited to speak on behalf of all Muslims to reflect the community’s successful assimilation into Canadian society. This anthology features the lived experiences of “good Muslims” and excludes the personal narratives of Muslims who are perceived by many in Canada as conservative, alien, and other.

Despite providing well-researched analysis on the politics of being Muslim in Canada, the essays – stressing the urgency of changing Islamophobic perceptions of Muslims – are inconsistent with the optimistic tone of the personal narratives. Perhaps separate publications for each type of writing would have been a more impactful contribution to the field.

The Relevance of Islamic Identity in Canada: Culture, Politics, and Self has done well to identify the need for publishing the ideas and stories of Canadian Muslims to challenge Islamophobia. Where it has fallen short in accomplishing its own aims, it has created an urgency for other Muslims to fill the gaps.