Over 8,000 postmasters and assistants work in Canada’s vast rural areas. You will find them serving behind the counters of the post offices in small towns and tiny hamlets. A CPAA (Canadian Postmasters and Assistants) office could be the familiar brick box you pass on the highway as it fleetingly becomes a rural town’s main strip. It could also be a simple wooden shack with antlers nailed above the door. Postmasters also work from their own businesses – for example, the local general store or, less often, out of their own homes.

It is usually and mistakenly assumed that only one union represents postal workers in Canada. In fact, rural post office workers have their own union, the CPAA (disclosure: I work there). Like the post office, it is a venerable institution, formed in 1902 in Stonewall, Manitoba, by a postmaster named Ira Stratton, who organized his colleagues to go to Ottawa to demand better working conditions. Since those times, the association has gradually improved the lot of postmasters, first by advocating and then, since the 1960s, bargaining. According to historian Betti Michael, “In many small communities, postmasters were seen as pillars of society. Their jobs were considered plums in the social hierarchy. If a member of Parliament found someone they thought deserved the job more than the postmaster, he could recommend his firing by merely charging that the postmaster had engaged in political activity, something that was denied him. It took more than 50 years of petitioning and lobbying by the association to secure protection for its members.” Nowadays the jobs are held almost exclusively (95 per cent) by women, who have had to fight hard for gender equality.

In 1992, on behalf of its members, the CPAA launched a massive pay equity suit that lasted almost three decades. Earlier this year, the organization negotiated a settlement of the pay equity claim and it is currently working with Canada Post to see that eligible members get their money. In its last round of negotiations, CPAA also managed to finally put an end to the infamous practice of the “one-third formula,” which drastically reduced the wages earned by a postmaster who was working out of her home or business. The CPAA has been fighting this injustice for many years. National president Brenda McAuley recalls one point in the long battle when she demanded to know how management could justify paying a worker a third of her hourly wage, and the employer responded that the postmaster could be “baking pies” when she wasn’t handling the mail, so of course she would be paid less for that time!

The CPAA has never gone on strike to advance its issues. It would be enormously difficult to organize and maintain an industrial-style strike, as there are generally only one or two members per far-flung office. The idea of striking has come up many times during the CPAA’s history but, as one opponent pointed out, “one can hardly imagine a lone postmaster in a small town or village going on strike all by himself, whilst two or three dozen of his townsfolk and patrons wait the chance to get his job.” However, the CPAA makes up for its inability to strike with a strong history of community organizing and grassroots action to fight postal cuts. When Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government threatened to close every rural post office in Canada in the 1980s, CPAA worked closely with the group Rural Dignity to resist the closures. A group called “The Singing Postmasters” was even formed to follow politicians around! They were ultimately successful in persuading the successive Liberal government to order a moratorium on rural post office closures in 1994. Today, there are still over 3,000 rural post offices across Canada. However, in certain circumstances, such as when a postmaster retires, that moratorium can be waived. For that reason, some postmasters are working well into their golden years. They keep their post offices open because they know what closing them would mean for the people in their area.

The importance of the rural post office cannot be overemphasized. A 2014 CPAA survey of municipalities and band councils on the closure of 1,700 post offices since the early ’80s reveals the broad consensus that closing a rural post office has a destructive ripple effect on its community, including a loss of jobs, economic stability, and cohesive sense of identity; there is likewise more isolation, especially for seniors and those with limited mobility or no access to a vehicle. Rural residents must also incur the time and expense of travelling farther for basic services. As a result, the study found that “the closures have been a severe blow to the body and soul of the rural community.”

Because rural post offices are so centrally situated and because their workers are so familiar with their communities, enhancing their roles as coordinators of community hubs makes sense.

The study also found that the majority of respondents actually wanted more services added to their post office. CPAA recently became the first postal union to get Canada Post committed to testing additional financial services in rural post offices. It has allied with towns such as Marmora, Tamworth, and Beachburg, where the remaining brick-and-mortar bank branches have pulled out, to the dismay of residents and local businesses. CPAA has also advocated that rural post offices should be central to environmental initiatives, suggested that better broadband could be offered there, and proposed that rural post offices could operate as safer transit hubs for those affected by the withdrawal of bus services from western Canada, an idea that was embraced by the NDP but largely ignored by provincial and federal governments. Because rural post offices are so centrally situated and because their workers are so familiar with their communities, enhancing their roles as coordinators of community hubs makes sense. The pandemic has made such ideas far less easy for governments to dismiss.

On the front lines

Like other postal workers, CPAA members were deemed essential and their post offices have remained open throughout the pandemic, although leaves were at first provided for those at risk and those with child care and elder care responsibilities. While outbreaks of the virus appeared in denser urban areas and at the postal plants in those areas, raising concerns about handling the mail, CPAA members and their offices have so far remained mostly virus-free. Like other front-line workers, postmasters and assistants have been bravely keeping at it, even when they feared for their own health and safety. But working in a rural post office during a pandemic comes with its own unique set of difficulties.

For example, protective gear is less available locally and takes longer to get to rural and remote areas. Many postmasters and assistants were forced to improvise their own protective equipment and practices while waiting for Canada Post to deliver. In Nunavut, for example, the post office became Iqaluit’s first drive-through while other postmasters kept the doors of their tiny offices locked and arranged for limited-contact transactions.

“The pandemic fatigue is heavy.… We’ve had to be creative to help our members get access to holidays and appointments.”

When supplies finally arrived from Canada Post, members felt safer but not completely. Janet Johnson, CPAA’s Manitoba branch president, reports that members complained that the shields installed at counters were inadequate, “flimsy pieces of plastic.” At the same time, she says, quite a few postmasters over the age of 70 continued to keep their post offices open, even after they were given the option of staying home as high-risk individuals, because “they love their work.”

As cases of the virus grew exponentially, media were reporting that urban residents were flocking en masse to rural communities. Many postmasters were concerned that snowbirds and out-of-towners were ignoring lockdown and quarantine orders. “I think the biggest problem was people not listening. People would come in, coming back from holidays,” explains Johnson. Their attitude was “I need my mail and you need to serve me,” she says.

At the same time, the move to online shopping that came with the pandemic meant that tiny post offices were suddenly overflowing with piles of parcels that used to be seen only at Christmas. This volume of parcels may become the new normal for postmasters. In one of his “Letters to the Front” that he emailed internally, T. Anders Carson, a director of the CPAA Ontario branch and a postmaster who was working at the Lanark, Ontario, post office at the time, writes, “I know the amount of parcels in our offices have exploded. One of the things that those numbers aren’t really telling us is the size of the parcels.… Usually at this time of year, we are cleaning up in our offices, doing inspections. But I’ve found with the foot traffic, parcels, and the public sending more through the mail, that it does feel as if the levels are Christmas. I know at that time of year you become zombie-like and do your tasks: make sure everyone is doing OK in the office, praise the good works, cut down on the mistakes that tie up the phone and then drive safely home without closing your eyes from the exhaustion.”

Johnson adds, “I don’t see this going away anytime soon. People have realized how easy it is to shop online. A lot of people who were on the fence, once they realized they had no choice, they don’t want to go into the stores.” She points out that small rural post offices were built for letters and packages, not the type of stuff that is shipped nowadays. “We’re talking tractor tires and barbecues.”

Johnson points out that the "leasing allowance doesn’t cover what it costs them to run that building. Some are getting $100 a month” for working at the post office. “They shouldn’t have to pay to work.”

Different forms of postal work take heavy tolls on the body – work that’s often unappreciated by the general public. In addition to obvious safety issues with lifting and carrying these loads, postmasters are running out of space to put them, filling up their storage closets and chasing customers to come and get their parcels. Carson reported, “I am doing second notices again religiously to remind people that we aren’t a holding cell.… We are a transfer station but can’t keep parcels for weeks on end. The parcels come in and we transfer them to our customers. Gentle nudge reminders have helped get much-needed shelf and floor space.”

Because of a shortage of temporary staff to backfill the regular post office staff, they are also not getting much breathing space or time off. It’s a serious health concern, in particular for those working under stressful conditions. According to Carson, “There are many of us out there who don’t have that staff and feel the pressure to keep working. I say do what you can to find some respite as we didn’t have Netflix time, or puzzle time, or downtime that our society had. We soldiered on getting those parcels to the people.… The pandemic fatigue is heavy.… We’ve had to be creative to help our members get access to holidays and appointments.”

In fact, adequately staffing rural post offices or even finding people willing to take on that work was a challenge even before the pandemic because Canada Post does not fully cover operating costs. Postmasters do get a leasing allowance toward the cost of their premises, but Johnson points out that the “leasing allowance doesn’t cover what it costs them to run that building. Some are getting $100 a month” for working at the post office. “They shouldn’t have to pay to work.”

Hearts of the community

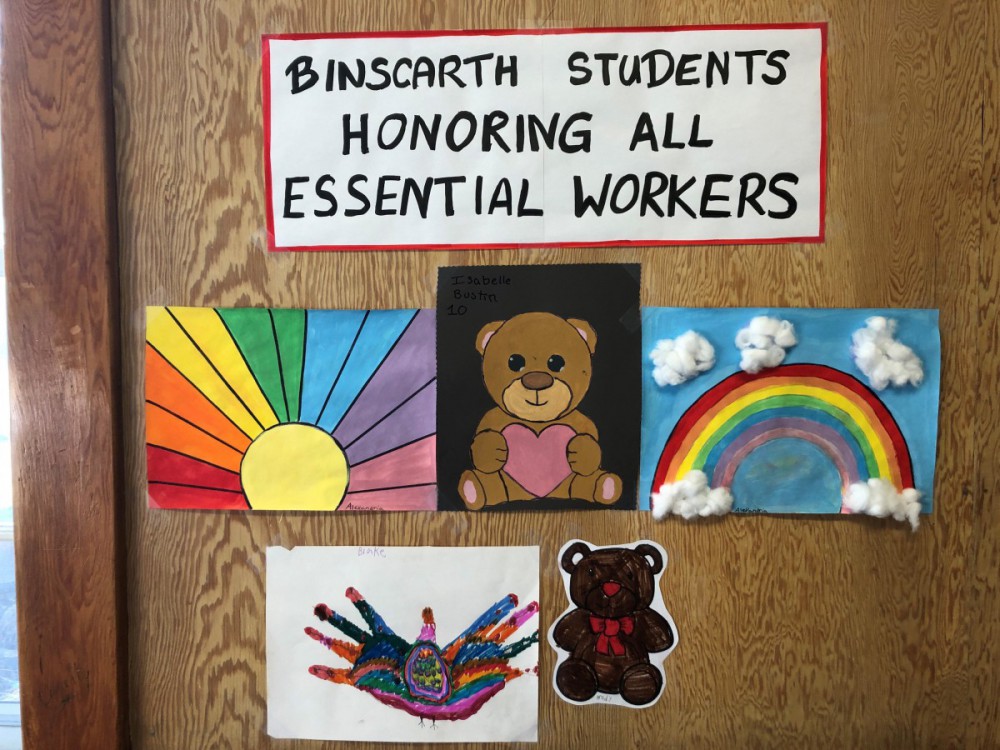

In spite of it all, postmasters and assistants have been living up to the CPAA’s description of the rural post office as the beating heart of a community. Post office windows everywhere show the ubiquitous rainbow and “It Will Be All Right” / Ça va bien aller.”

In Manitoba, the CPAA branch launched a morale-boosting “Rainbows and Teddy Bears for Essential Service Workers” campaign to decorate post offices. “Everybody here was so tired of seeing the stop signs and the scary signage that they wanted to do something more positive and show their support for everybody who is working through this,” said Johnson. “It brought a little bit of cheer to rural communities.”

One postmaster put a basket outside her post office with sidewalk chalk and colouring pages, while others reached out to teachers to ask them to assign virtual schoolwork for the kids to draw pictures for the post offices. Others built counter displays and created beautiful window art.

"She came in and brought chocolate eggs to say thank you for being open. For being here.”

The profound caring that rural post office workers show for their communities is reciprocated in touching ways. Many customers have brought in gifts and sent appreciative, heartfelt cards and letters to their post office workers. A thank you to exhausted front-line workers “goes a long way,” says Johnson. In April, Carson reported that “a young girl who works in the now-closed chocolate store across the way from the post office … came in mid-week, when I seemed to be having a low point. The realization that we were working harder than at Christmas, the parcels jumping up exponentially and keeping the flow of some semblance of commerce moving. She came in and brought chocolate eggs to say thank you for being open. For being here. And the public knows that we are here.”

The public knows. Do the politicians know? It has been an uphill battle to make policymakers at all levels even aware of the CPAA’s existence. To get them to listen to the issues and ideas of postmasters and support expanded postal service in rural Canada might be an ongoing struggle, but it’s one well worth engaging in.

Update, November 12, 2020: This article originally stated that there are over 6,000 rural post offices across Canada. While there are over 6,000 post offices in Canada, only around 3,000 of them are rural.