“Buildings are nice, the environment’s important, but more important than that is a sense of autonomy … [that] people at that school have a sense that they’re in control of their destiny.” – Randall Fielding, Fielding Nair International

Stay active and healthy. Exercise my heart. Move my muscles. Play outside. These exhortations line every other page of my daughter’s school agenda. While the virtues of exercise and play need no elaboration, what is odd about this messaging from the Regina Public Schools board is that it comes at a time when so many walkable neighbourhood schools are being shuttered as part of a 10-year “renewal” that began in 2007.

The real message: being active is an individual choice, even when children are increasingly forced to spend their before- and after-school hours trapped in cars and buses.

This concrete absurdity reveals a city caught up in the global rush to rationalize schools along neoliberal lines. In districts as dissimilar as Cape Town, Chicago, and rural Nova Scotia, governments have deployed the same logic to eliminate “underutilized” schools. Lessons in efficiency, taken from the world of corporate finance, are passed down from higher to lower levels of government, with responsibility for success falling on those on the receiving end. It is the real trickle-down.

Given the mandate for school boards to do more with less, drastic staff cuts often follow school closures and mergers. As of 2013, Saskatchewan public schools would have needed to create more than 700 full-time education assistant positions simply to equal 2007 levels of classroom support. Combine fewer staff members and climbing numbers of students with intensive needs and you have stressed schools, teachers, and families.

To pursue this austerity agenda, officials have had to ignore research linking frequent school changes with poor social and educational outcomes. School closures compound the pervasive instabilities of poverty, precarious work, and scarce and substandard housing that are prosperity’s backdrop.

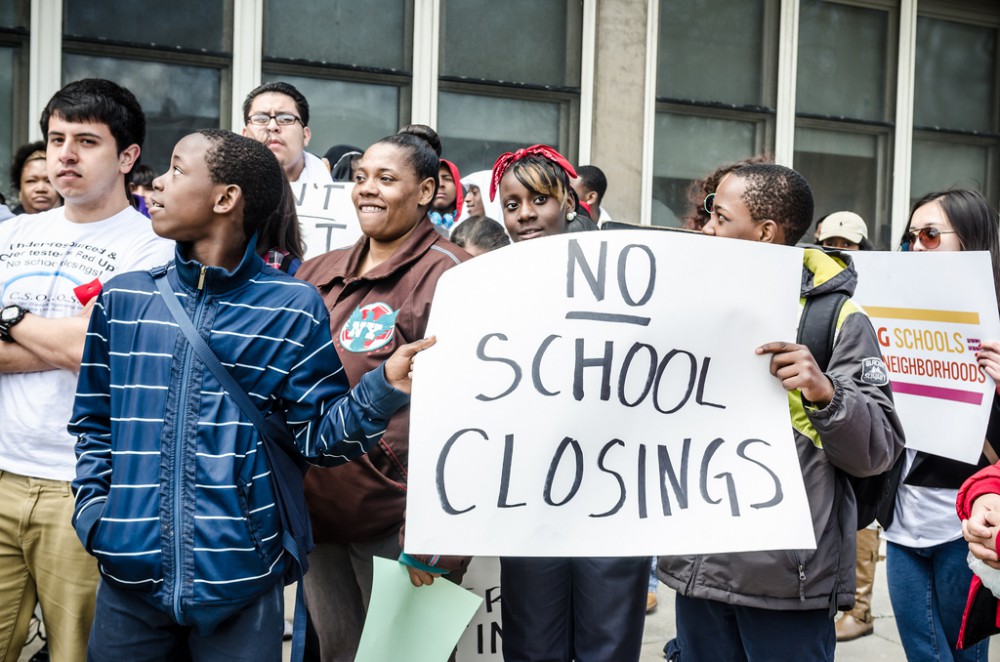

As the only accessible decision makers, the Regina Public Schools board has had to deflect concerted resistance from parents and the community group RealRenewal who, throughout the consultation process, have put forth alternatives, produced studies, and enlisted experts to challenge the assumptions and anticipate the effects of the imposed reforms. But as has become custom, all the important decisions were already made.

Even if schooling is not broken, as it is popular to say, it is thick with plans that run at cross purposes. Take the clash of two other far-reaching trends now converging in Saskatchewan: open plan schools and standardized testing.

Cells and bells

The statement endorsing local autonomy at the top of this article would be unremarkable if not for its source. Randall Fielding co-heads the design and planning firm Fielding Nair International (FNI), a global pioneer in the current wave of open plan schools. Among its school projects in 30 countries, FNI has designed open plan facilities in Regina and Vancouver, with many more planned for Saskatchewan, Alberta, and B.C.

Envisioned as a break from what Fielding calls the “cells and bells” model of the enclosed classroom, the firm’s designs take guidance from progressive educators such as Deborah Meier, founder of the small schools movement, and Alfie Kohn, the foremost critic of standardized testing. Against generic curricula and the corralling of students for an industrial economy, their designs are meant to encourage critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity. Standardized testing, meanwhile, belongs somewhere near the apex of shallow, “degrading” learning, to use Kohn’s pun.

Open schools, then, are to be an infrastructure response to educational practice. In a review of open plan schools, both past and present, leading researcher Neil Gislason found their success is entirely reliant on having aligned curriculum and teaching methods, including collaborative teaching and student-directed learning backed by substantial resources and training. Where these were absent, teachers found the layout dysfunctional and took steps to restore the enclosed classroom.

So the open plan can work, but it is experimental and requires a serious commitment to expanded resources and training. Gislason fears the “amnesiac silence” regarding past problems with the open plan model bodes poorly for the current wave of such schools.

FNI’s ultimate vision, in any case, is to de-school: to “dissolve schools” in favour of “learning cities, learning communities … where you blur the boundaries between institutions – universities, K-12 schools, and residences.” This radical reconception doesn’t come with the multi-million dollar buildings that are FNI’s core product, however.

The Saskatchewan Party government, now scrambling to cope with a population influx, has committed to building nine joint-use schools through the public-private partnership (P3) model at a cost upwards of $420 million, with construction for all nine facilities bundled into one tender.

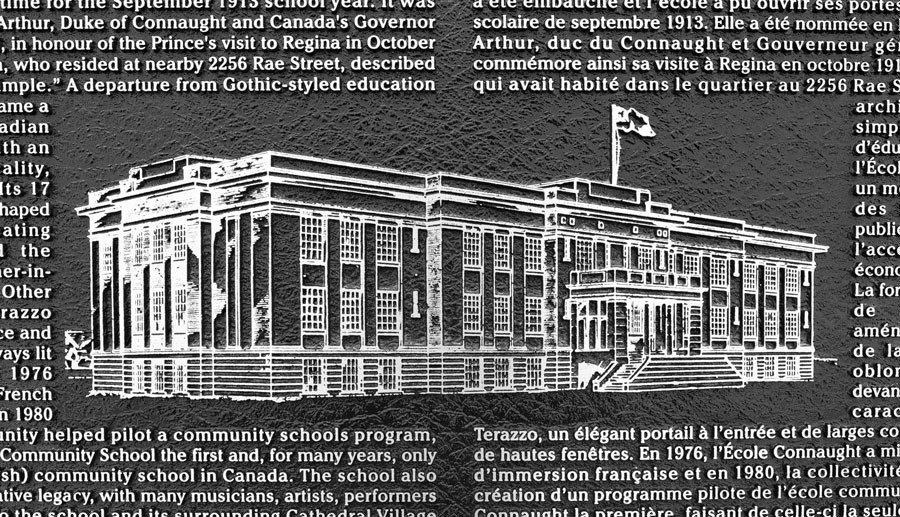

In the space of six years, Saskatchewan has gone from closing “underutilized” schools to joining Canada’s “infrastructure gap.” This while sound buildings lie vacant, their outstanding repairs worth a fraction of the new builds. Regina’s oldest school, the 100-year-old École Connaught Community School, is marked for teardown, with the school board itself blocking RealRenewal’s every effort to conduct a thorough structural assessment of the historic building.

Efficiency, then, is not the answer to the riddle of what drives school reform.

A standardized racket

Standardized testing is also not cheap. The initial phase of implementation in this province alone was slated to cost $5.9 million.

A bit late to join the Texas-inspired testing craze that is now losing favour in Alberta, Ontario, and even Texas, in April the Saskatchewan government succumbed to public pressure, retreating from former Education minister Russ Marchuk’s call for standardized tests as the fix for high dropout rates among Indigenous students. These system-wide generic tests are in fact notorious for their cultural bias. While the tests assume a homogenous student population, factors like poverty, disability, and cultural difference are masked as performance failure.

Instead of pulling youth in, “standardized tests marginalize and push them out,” says University of Regina education professor Marc Spooner. Further, such tests are a blunt instrument. The reality, says Spooner, is that “they do not know what they are measuring.” Low scores might indicate a large class size or a teacher who spends more time facilitating real learning than “teaching to the test.”

In fact, study after study has shown that variations in test scores have little to do with quality of instruction and everything to do with income inequality, levels of parent education, and neighbourhood demographics. Even where scores are high, the tests reflect lower level thinking and shallow, rote learning.

But they are not without effects in the classroom. They do restrict teachers’ freedom to adapt curriculum for their students. And they do succeed in driving competition. In this way, they resonate with market logic, pitting students, teachers, and schools against each other and turning students who do not thrive by such narrow measures into a liability for group success.

Combining this shallow test-driven model of education with FNI’s open plan buildings, meanwhile, is simply incoherent.

Consolidating control

If the preference for open plan schools does not arise from any commitment to progressive education or what FNI bills as “democratic architecture,” what is it about?

Part of the answer is curb appeal: we want to join the ranks of 21st-century global cities. But we also want to pry open public infrastructure (worth an estimated $500-600 billion nationally) for private profit, while appearing to balance budgets. The privatization of public assets is a hallmark of the present era of capital accumulation, part of a process renowned geographer David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession.”

Closing schools takes decades of neglected repairs off the public books, while the new facilities are financed by future debt with annual lease payments for their use. It is all very creative, coupling the gloss of future-forward facilities with the crisis created by closing existing schools.

While, broadly speaking, the infrastructure gap is real, it too is engineered to the extent that federal infrastructure spending (relative to GDP) went from being two to three per cent in the 1960s and ’70s to just 1.5 per cent by 2000. Following the brief stimulus to reboot infrastructure spending, the Conservatives continued to ramp down public investment. Their 2013 economic plan further mandated that all federal funding for projects over $100 million be conditional on a P3 screen. The screen is carried out by PPP Canada, a Crown corporation dedicated to promoting this very model to municipalities, provinces, territories, and First Nations reserves.

Not the rude privatization of the 1980s, P3s introduce variations on the drive to expand markets and raise profit margins. The softer sell partnerships give negotiators room to work out the preferred mix of private design, construction, financing, operation, and maintenance of services. In this way, infrastructure has served as a crucial inroad to solidify a neoliberal mode of governance that seeks to dissolve unions and reduce workplace standards.

Formed in 1993, the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships (CCPPP) is now an influential lobby that draws its 1,200 members from all fields with a stake in P3s: international financiers, lawyers, and construction consortia, along with current and former elected officials. Elites float easily between roles. A keynote speaker at a CCPPP annual conference is as likely to be Kathleen Wynne, premier of Ontario, as it is to be Jin-Yong Cai, CEO of the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group, whose business is to privatize public assets in developing countries.

P3s are said to strike a bargain where risk is transferred to private companies who, in exchange, receive a better return on investment. The reality is that when P3s have left a trail of corruption and failure the cost is always shouldered by the public that pays for and depends on the services.

Marc Spooner has said that standardized testing “makes the most sense the further you are away from the classroom and students.” This is where the odd mash-up of current education initiatives finds common purpose: in their antipathy to local control and collective participation.

While there are limited avenues to provide feedback to elected officials and bureaucrats and to hold them to account, such avenues are virtually non-existent when it comes to private corporations. The private firms eager to build, finance, and maintain our children’s schools are not subject to democratic mechanisms, such as Canada’s Access to Information Act. Their ownership is easily dissolved or transferred, their executives rarely held personally accountable.

Educated and pushing back

In April, concerted pressure and broad mobilization by communities and teachers in Saskatchewan paid off. Education Minister Don Morgan announced that the province was scrapping its plans for large-scale standardized testing. “I don’t think it benefits the students and I don’t think it benefits the province,” said Morgan. The pushback was so successful the minister admitted that the term “standardized testing” has “become absolutely toxic” in the province.

P3s may be a harder target, however. Dedicated government departments and enabling legislation have entrenched this project delivery method, and P3s have become a worldwide benchmark practice in infrastructure investment.

But there are points of weakness. Despite the fact the federal government holds the purse strings, most infrastructure projects fall under provincial and municipal jurisdiction. Even in Alberta, where the (recently ousted) Premier Alison Redford has been the Honorary Chair of the CCPPP since 2012, the Calgary Board of Education has turned away from P3 builds in favour of a standard design-build process, citing untenable delays in construction. In Saskatoon and Regina, communities have mobilized to force school boards to adopt motions demanding provincial accountability and transparency with respect to P3 plans.

Such efforts form part of a growing resistance to neoliberal school reform that can draw strength from the rank-and-file militancy of the Chicago Teachers Union and the 2013 Seattle teachers’ boycott, which successfully forced Seattle public schools to abandon standardized tests at the high school level. In 2003 in El Salvador, where the P3 sell-off of telecommunications and electricity precipitated massive layoffs and wage cuts, direct action culminating in massive street protests effectively halted further privatization.

Even on its own terms, the P3 boom is acquiring a reputation for cost overruns, construction delays, corruption, bankruptcy, and routine difficulty attracting multiple bidders. Communities from Nova Scotia to B.C. – where Abbotsford residents defeated a P3 proposal for their wastewater treatment plant – are making connections to share findings and arm themselves with facts to push back against the P3 agenda.

The stakes are high. If this opposition is not successful, not only the fate of schools but also those of roads, prisons, hospitals, social services, pensions, transit, energy, and water could be in the offing. The sky could be no limit.