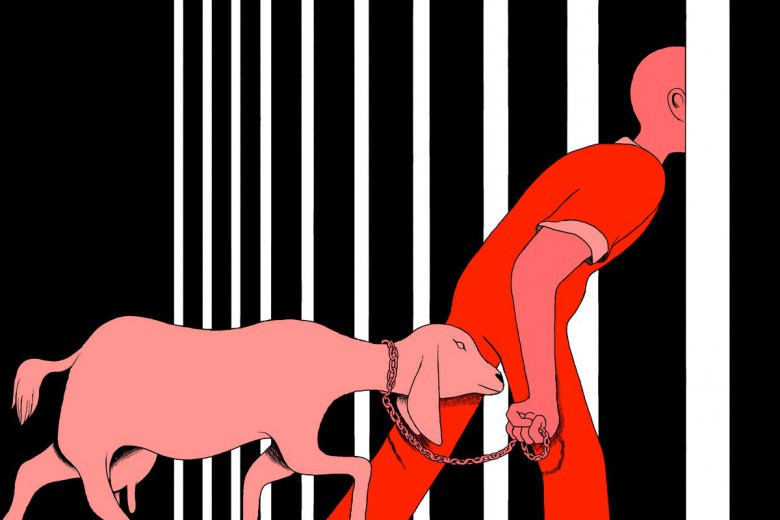

In major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, millions of migrant workers from poor villages make up approximately 40 per cent of the urban labour force. Unlike affluent people, who can afford to insulate themselves from the harmful effects of pollution, marginalized Chinese people on the lower end of the socio-economic scale are forced to bear the noxious brunt of China’s economic juggernaut.

Class Privilege

Blue skies can be rare in some parts of China.

Air is considered clean if the level of PM2.5 is 50 or lower, and hazardous if it is 300 or above. Throughout the year and particularly during the winter in Beijing, when more coal is burned for heat, it’s not uncommon for pollution levels to exceed 500, or about 20 times the World Health Organization’s recommended limit.

The effects on residents’ health are dire. Air pollution in Beijing has been linked to lung cancer, heart attacks, and premature births.

China’s environment ministry recommends that residents stay inside when the PM2.5 level hits 200 for more than 72 consecutive hours, but staying inside is not an option for the vendors, shopkeepers, construction labourers, and other outdoor workers upon whose labour Chinese cities’ economies depend.

Wealthy residents of Beijing or other large Chinese metropoles are, of course, not immune to the cornucopia of deleterious health effects linked to poor air quality. But middle-class people – those who live in households with annual incomes ranging from C$6,000 to C$25,000 – have resources that enable them to significantly reduce the impact of toxic air.

According to professor Michael Brauer of the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health, “Wealthier individuals may live in homes or work in buildings with mechanical ventilation systems or air conditioning, or have air purifiers … all of which lead to reduced levels of many indoor pollutants…. In addition, they may also live on higher floors in high-rise buildings where pollution levels are lower than at street level. Wealthier populations may also be able to temporarily remove themselves during very high pollution episodes by travelling to cleaner locations.”

Air purifiers are, in fact, big business in China, and sales have increased dramatically over the past several years. But the average price for a foreign brand air purifier – which is generally considered to be of much higher quality compared to a domestic purifier – is around 2,000 to 3,000 yuan, or about C$550 to C$660. A white-collar professional in Beijing might consider 2,500 yuan a small price to pay for clean air, but according to the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security, given that the average salary of a resident of Beijing is 77,000 yuan (C$17,000) per year, the investment in an air purifier is hefty.

Clean food – for some

When asked if he’s concerned about the pollution in Beijing, delivery driver Li Meng Lei shrugs.

“I guess so. I’m willing to move to another city with less pollution, but I don’t have an education,” says Li.

Six days a week, the 30-year-old zips in and out of Beijing’s treacherous traffic, delivering packages to businesses. Li isn’t originally from Beijing, but he’s lived in the city for two years.

He wears a helmet, but he doesn’t wear a mask.

“I’m used to [the air pollution]. Every day since I was little, I’ve seen it. Where I come from, we call it smog.”

Eating and drinking in China can be a gamble, too.

Over the last several years, there have been numerous high-profile food safety scandals in China. In 2008, milk powder tainted with melamine, a toxic industrial material, killed six babies and made hundreds of thousands ill. Since then, watermelons have exploded from the misuse of a growth accelerator chemical, pork has been contaminated with a detergent additive, rat meat has been passed off as pork, steamed buns have been tainted with pesticides, and thousands of dead pigs have drifted down Shanghai’s Huangpu River, one of the city’s primary sources of drinking water.

Against this backdrop, expats and wealthy Chinese are willing to spend a premium on food they believe to be safe. Chinese and foreign entrepreneurs have stepped into this need by privatizing food and water marketed as safe.

The organic food industry, for example, is booming: sales of organic foods reached 80 billion yuan in 2012 (C$17 billion). Residents of cities like Beijing or Shanghai can place an online order from an organic farm, and have seasonal food grown on that farm delivered within 48 hours. Many farms also deliver meat, poultry, and grains.

Though organic food consumption represents only about one per cent of total food consumption in China, that number has tripled since 2007. And the Chinese water filter industry expects market sales to reach 7 million units in 2017, up from 1.2 million units in 2010.

Organic food is popular with middle- and upper-class Chinese families in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai, but pesticide-free meat and produce doesn’t come cheap. A one-time delivery of six kilograms of vegetables, a dozen eggs, and a bag of rice from an organic grocer can cost nearly 300 yuan (C$66) – five times more expensive than a standard supermarket trip. Water filters for the shower and kitchen sink typically cost about 1,000 yuan (C$220) and 3,000 yuan (C$660), respectively.

The reality for average-income families in cities like Beijing is that they cannot afford the luxury of peace of mind when it comes to what’s on their plate or flowing from their tap.

State complicity

Transferring the burden of pollution from the rich to the poor is government policy, according to Judith Shapiro, author of China’s Environmental Challenges and professor in the Global Environmental Politics program at American University in Washington, D.C.

“China’s horrific environmental problems are no different from those elsewhere in one key respect: An underlying dynamic is the displacement of environmental harm from wealthy, politically connected populations close to the center of power to the more vulnerable in the periphery,” explains Shapiro.

“While it is easy to celebrate the rising middle class’ resistance to highly polluting factories … all too often they simply move to more remote areas. In China, we see this dynamic in the relocation of landfills from city centers to outskirts, of polluting enterprises from cities to rural areas. We also see more pollution move from the wealthy East to the less developed West, where ethnic minorities are in a poor position to fight back….”

Chinese people from across the socio-economic spectrum are not accepting this without a fight, however. Over the past year, there have been scores of environmental protests against polluting factories, power plants, and waste incinerator projects.

And there are indications that the government is listening. During the National People’s Congress in March, President Xi Jinping vowed that Beijing would “punish, with an iron hand, any violators who destroy [China’s] ecology or environment, with no exceptions.”

Chinese leaders realize that the state’s political legitimacy is entirely dependent upon a continued upward trajectory of citizens’ quality of life. Cities blanketed in a thick, brown haze don’t fit that vision.

That’s why it is possible that what Shapiro calls “state-led environmentalism” is not a series of empty gestures. Legislators in 2014 passed the first amendments to China’s environmental protection law in 25 years, promising increased powers for environmental authorities and tougher punishments for polluters. More than 8,000 people were arrested within the past year for a variety of offences, ranging from failing to complete environmental impact assessments to ignoring warnings to stop polluting.

But China’s pollution problem is critical, and it will take far more than throwing handfuls of factory owners in prison to clean up the smog-choked air of cities like Beijing.

Can the central government – which prides itself on its ability to take bold and decisive action – significantly improve the country’s air, water, and soil quality? All things in contemporary China seem to be possible, but working-class Beijingers probably shouldn’t hold their breath.