When I was 12, I was finally allowed to take the city bus alone to and from Saturday gymnastics. After class, even if I took my time and helped my coach put away the mats, I would have to wait 16 minutes at the stop before the bus came. One afternoon I stood at the stop in my leotard and shorts, making puppet shadows with my topknot and the shape it made against the afternoon sunlight on the sidewalk. A man crept up to the bus stop in his brown car with its brown seats and beckoned me over with his rust-stained fingers. He told me the bus wasn’t coming and that he would give me a ride. I backed away, pretending like I hadn’t heard him. I stood frozen at the bus stop and stared at the line between my block of sidewalk and the next, lining my topknot shadow perfectly in the middle, like an arrow pinning me to that very spot. I pretended not to see him as he circled the block twice until the bus came. He wasn’t you though, because you and I are the same age and this was a long time ago, and the man with the brown fingers in the brown car that day was older than my dad.

I was 13 and Amanda K. had the biggest boobs in the whole seventh grade. We were all still wishing to fill our training bras; meanwhile, her bra straps announced the passage to the other side, like ropes holding up the drawbridge of womanhood. There was probably an Amanda K. in your school, too. And maybe your Amanda K. and her bra straps also got called into the principal’s office before first period was over, and then also got sent home, missing math and chem because exposed bra straps made it hard for boys like you to memorize multiplication. We all learned a valuable lesson from Amanda K. while she was home, missing class, and maybe you did, too: that girls were the gatekeepers of boy’s urges.

We were 15 and he was 19. He insisted all three of us – Jen, Tiff, and me – squish into the front seat of the car beside him as he drove to the liquor store. Tiff had stolen her sister’s Revlon Cherries in the Snow lipstick, which now slicked all six of our lips. My contribution to the evening was a water bottle one-third full of Malibu rum, a splash of peach schnapps, and topped off with vodka. Jen didn’t bring anything but said she would score us a cigarette – hopefully menthol – that we could smoke behind the 7-Eleven.

We asked this guy to buy us smokes and he said he had some at his house and we could stop on the way there and he would buy us real booze. We crawled into his car, not your car, and I quickly felt dizzy from the artificial scent of not one but two orange tree-shaped fresheners hanging from the rear-view mirror and whatever odour they were trying to cover up. I watched them swing back as he started the car in second gear, slamming the gearshift between Jen’s legs, forcing his hand uninvited and unavoidably deep underneath the hem of her school uniform skirt. I felt her body tense beside me and I watched the little orange trees hit the window, and I heard her gasp and I felt queasy.

The summer before I start Grade 12, I am baptized in the streets and given the names that will be used in attempts to get my attention for the next two decades: hey baby, darling, nice ass, hot stuff, and sweet cheeks.

In university, I go to a party at a frat house that is floored with linoleum from the ’70s. I am drinking beer from a keg. All the girls are drinking beer from the keg, except for the ones drinking while standing on their heads and those others who are crouched at the bottom end of a funnel while the boys at the top, none of whom are you, keep pouring and pouring. I go to find a bathroom and I see my roommate leaning off the back deck, with a boy who isn’t you pulling on the waist of her Levi’s. He tells me they are fine, and I really have to pee, so I promise to be right back, but then I see the babe from my Phil class and I forget to go right back.

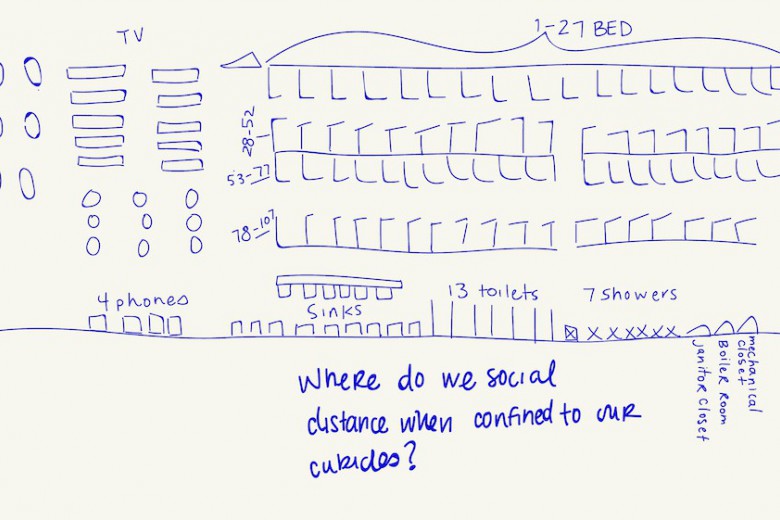

Later in the evening, the pattern on the floor is moving like a sundial only 19-year-olds can see and it tells me it is time to go home. I can’t leave without my roommate, because the posters all over campus remind us that rapists will stay away if we don’t walk alone. I can’t find her, so I run-walk all the way to my dorm and it kind of sobers me up. I crawl into my bed without making a noise and I realize my roommate is there but she isn’t alone, and I hear him tell her to be quiet and I hear her say they should stop, really they should stop, and I hear him having sex with her and I don’t hear her saying no but I also don’t hear her saying yes.

I’ve just finished my degree and I have had a boyfriend who isn’t you for eight months. We are going out and so I put on the dress I wore when I met him, because it is the most flattering dress I own for how the fabric clings with all its fragile strength to my collar bone before giving up and plunging recklessly under my sternum. I meet him at the restaurant and we see a girl with a dress much more modest than mine, and he makes a comment under his breath that she is just advertising her daddy issues. I assume he is implying that her issues stem from a dad who touched her in wrong ways, and if that was the case I could fill up one hand with friends I knew whose dad or stepdad did that, and if we extended the source of said issues to include uncles and swim coaches, or even a boss grabbing an ass, I would need more fingers and toes. The ones I know had a hard enough time whispering about it, much less advertising it.

One night, two years and a few boyfriends later, I am out dancing with my friends and men are imposing their way into our evening uninvited, and they don’t back off until we lie and say our boyfriends are coming, because they will respect an imaginary, made-up man before they respect us. You aren’t a journalist, so I know you didn’t write the advice in the paper about how to not get raped by the creep attacking women lately. It’s all shit like don’t drink, and don’t walk alone, and don’t go out at night, but I take it seriously and decide to cab home and not walk like I usually do.

I am in the cab and two minutes into the ride, the driver offers me money for sex. I call the taxi dispatcher, who thinks it is reasonable to forward me to the complaint voicemail, so I jump out at a red light. The cab driver follows behind me in his car down an alley, offering me money not to tell on him. I walk four blocks past my house, so he doesn’t know where I live, before he gives up. Planning a “safe ride home” turns out not to be so safe.

There are women for sale in my neighbourhood almost any time, but there is much more selection after dark. I make a point to know all the workers on my block by name, and memorize things like hair colour, height, tattoos and scars, so that I can vouch that somebody paid attention, if ever they don’t show up for work. Sometimes when I am waiting for the bus, or a ride, or the light to change, or doing anything that has me stopped near a corner, a car will slow and the brake lights will flash – a not-so-subtle way of selecting me off the shelf. You say this bothers you, and I say, “Yeah, me too.” Not because I think I am better than the women selling – in fact, it sparks this rage because I feel that we are all the same. Although he never laid a hand on me, the man in the car asking for a price check on my body is committing violence.

Since we are talking about where I live, and the place that I call home: there is a tower going up behind my house, and for three straight mornings last week, men’s voices rained from above as I stepped out of my house. I couldn’t see their faces, as they were five stories up, but I am pretty sure none were you, offering opinions about my cut-offs, my crop top, my baggy T-shirt, and my dog-walking capris.

On the fourth day I stood on my porch and imagined if the clinic where I work as a nurse was above a business, with families and neighbours walking by underneath, and what would happen if I spent my day yelling my sexualized thoughts about people passing by, getting bagels, buying coffee. I think that people would complain, businesses would suffer, mothers would not bring their children anywhere within earshot, and the police would surely be called to deal with the nurse yelling “hey, hot buns” to strangers from the window.

I marched across the alley, my flip-flops beating with confidence, and I sought out the site manager. He told me to relax; he told me they were really nice guys and that I should learn to take a compliment. I wonder why, if it’s just a friendly compliment, they don’t yell it at other men.

It’s not you telling me to smile, to shake it, to show you my tits, or to call you, while I am walking to work, going to buy tampons, thinking about global warming, or just wanting to be left the fuck alone. At least I am pretty sure it’s not you, but things are often said from passing cars, in the part of the street with no light, in the park on a noisy afternoon, or from across the road and other places where I can’t always see who is talking to me, so I can’t be certain. Even after I have plotted new routes and added time to my walk to the bus, the voice that I am almost sure isn’t yours still finds me.

This isn’t even as bad as I have heard it can get. When I interrupt my thoughts about important things to replace them with thoughts about the fastest way away from men who aren’t you, when I say nothing, I sometimes then become ugly-dyke-bitch-whore-I-wouldn’t-fuck-you-anyways. I know girls who have been spit on, followed to their door, or had bottles thrown at their head. And worse. Not nearly as often, but sometimes, it can get so much worse.

So I am 34, and this conversation starts how it always seems to start. I have had it countless times, with men who are just like you. I am ready when you tell me that it’s not you, and it’s not all of you, and I should know you’d never do that, and why am I so angry? And besides, aren’t there more important things for me to be upset about? You are littering our exit with questions it isn’t my job to answer and you’re standing in the doorway to my equality, where you are taking up a lot of space. You mention something about a bad apple and I start to want to fall asleep.

Because when you say it wasn’t you, the truth is you are right. You didn’t do all of these things to me, or any girl, any woman, ever. In fact you didn’t do anything… and therein lies the problem. You didn’t speak up. You minded your own business. You let it enter your mind that she deserved it. You looked at pictures not meant for your eyes. You believed him because he’s a nice guy. You looked away. You felt uncomfortable but not enough to say anything. You dismissed it as a joke. You ignored all of those times you saw things that you knew weren’t right and you didn’t make it your problem. Instead you made it mine, and you’re not listening to me now, you’re just waiting for your turn to talk – so yes, you are right it was not you. You just let them all take parts of us. Robbed, and stripped, and put on display. I know you’re a good friend and that this may be hard to hear, but what I need is to find a way for you to see that it’s the silence you keep that allows their kind to be.