My citizenship ceremony last year was supposed to mark the official end to my sweet-and-sour decade as a non-citizen in Canada. But instead of feeling the nationalistic euphoria expected of me and the crowd of newly minted citizens who enthusiastically, anxiously, or robotically waved their flags and recited the citizenship oath, affirming “true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, her Heirs and Successors,” I found myself capsizing with a sense of ambiguity and melancholy.

As someone with a racialized body and accent, I knew that gaining citizenship was a formality that would not change the fact that I am an “Other.” I also knew that while I put an end to my status as a non-citizen, people, usually racialized and from outside of Europe, continue to be blocked from opportunities afforded to me. And I knew that in order to go through the citizenship process, I had to perform acts that I found truly repulsive.

Becoming a citizen requires passing a citizenship test that often stumps citizens born in Canada. The study guide for the test pushes the narrative that Canada promotes “peace, order, and good government”; Mounties, it tells us, were established to “pacify the West.” To pass the test, I gave what I knew to be inaccurate answers that contradict the experiences of Indigenous peoples and newcomers, and normalize the authority of the state.

Those who pass the citizenship test are invited to attend a ceremony, during which non-citizens, policed by staff, sing “O Canada / Our home and native land.” The fact that it is Indigenous land stolen by settlers is inconsequential. Toward the end of the ceremony, soon-to-be citizens must shake hands with official representatives of colonization: a Mountie, a judge, and a military officer. At my ceremony, the officer bragged about his involvement in “peace missions” on my home territory.

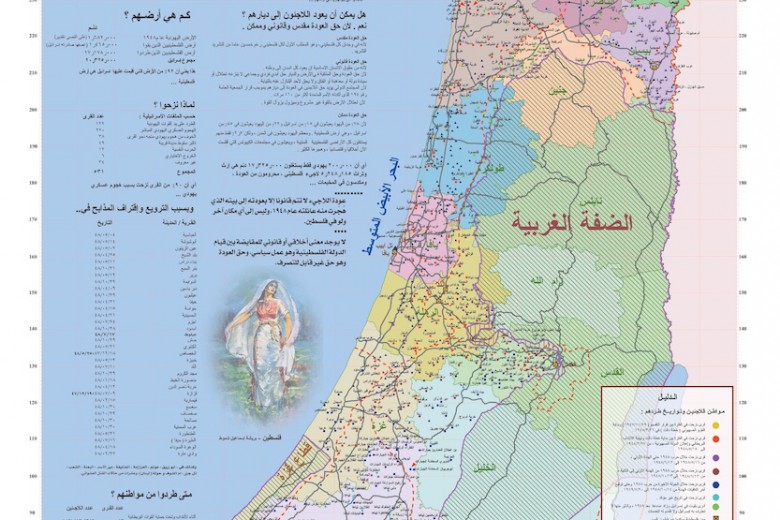

My father was born in Palestine under the British Mandate in 1946. Two years later, as Zionists were celebrating the birth of Israel and their full rights as citizens, my father’s family was forced into exile in Dubai, where I was born, without roots to plant or wings to fly. The immigration system in Canada that allows a selection of non-citizens to become permanent residents and later citizens does not exist in Dubai. Even though I was born in Dubai, and even if I had decided to live there my entire life, I would never be a citizen of the United Arab Emirates. Over 90 per cent of Dubai’s population are non-citizens with very limited, if any, political and social rights. This migration system allocates renewable short-term visas that separate families and create conditions of modern slavery, exploiting human bodies for material and political gains. Nothing better exemplifies this process than the case of the sunburned migrants from South Asia living in labour camps. They are the fuel and heart of the economy, yet they live in wretched and hazardous conditions without immigration status or a path to citizenship. Perhaps this rings a bell for certain people in Canada.

So, while I will never be a citizen in Dubai, my Canadian citizenship does not automatically change my identity or my status as a migrant, though it does allow me to access privileges like the freedom to visit Dubai without paying for a visa and to re-enter Canada. But no matter what I do, the unconscious bias in Canada will be skewed against transnational subjects like me. A stark reminder of this was the night that an inebriated white man yelled “terrorist!” at me. Canadian hospitality and welcome rest on a notion of territoriality and require the ability to refuse entry or full inclusion to those considered “Others.”

I dream of a world that is quilted by and for Indigenous peoples and transnational migrants, without passports – passes or ports. We need to struggle against the monopoly of state power and control, and offer alternative institutions and relations that are durable and sustainable. I want an alternative that asserts Indigenous sovereignty, and with it, the shedding of the monopoly over the designations “legal” and “illegal.” As the voices on the margins continue to call, “No one is illegal! Canada is illegal,” bringing this vision to life means more than reforming the oath or nominally mentioning treaties; it takes more than recognizing 150 years of colonization. This is about a mutual love and respect that knows no borders and is defended by each of us (and especially those with citizenship and white privilege) standing up for justice and freedom from oppression.