By Makeda Silvera

Sister Vision Press, 1989 (First Edition: William-Wallace Publishers, 1983)

In the introduction to Silenced: Talks with Working Class Caribbean Women about Their Lives and Struggles as Domestic Workers in Canada, Makeda Silvera introduces her readers to Noreen, Julie, Angel, Savitri, Hyacinth, Molly, Myrtle, Irma, Primrose, and Gail (all pseudonyms). “These women have never been heard,” she writes, referring not only to these particular women but also to other women like them – that is, migrant domestic workers.

For most of the 19th century, domestic labour was performed mostly by European immigrant women. But the West Indian Domestic Scheme of 1955 launched the recruitment of women from the Caribbean, which allowed women from British colonies (mostly Jamaica and Barbados) to work in Canada for a year as a domestic worker before gaining landed immigrant status. In 1973, due to the continued demand for domestic labour and the state’s interest in replaceable labour, the Domestic Scheme was replaced by the Non-Immigrant Employment Authorization Program (the origins of today’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program).

First published 1983, Silenced is a collection of narratives edited from interviews with migrant domestic workers, conducted by Jamaica-born and Toronto-based writer Silvera. Domestic work – including child care, elder care, cooking, cleaning, and other forms of immaterial labour – takes place in spaces where women work, and often where women sleep.

In the introduction to the second edition, Silvera frames what she calls a “female sensibility” in pursuing “oral history as a methodology.” Silvera’s interviewing, contrary to methods in social research of the time, is warm, self-asserting, and open. The result is a toggling between action and a more emotional or aesthetic impulse, a look at the language that emerges in the condition of being silenced.

All of the women hail from the English-speaking Caribbean: Trinidad, St. Vincent, Antigua, St. Lucia, Guyana, and Jamaica. Their stories record sexual abuse, long hours, low pay, unfulfilled contracts, vulnerability to illness, excessive charges for room and board, diasporic longing, family separation, entangled intimacies, forced overtime, unpaid wages, and sexual regulation.

While Angela Davis has described housework as “invisible, repetitive, exhausting, unproductive, uncreative,” these stories show not only what that drudgery looks like, but also how always-racist capitalism informs the dread and dreams narrated here. Irma, for instance, endures the racist taunting of the children she cares for and describes the complicated effects of the gendered and sexual violence she suffers at work: “For I don’t want no sex from him,” she says of her employer’s brother. “Sometimes I feel like just stabbing him with the kitchen knife.”

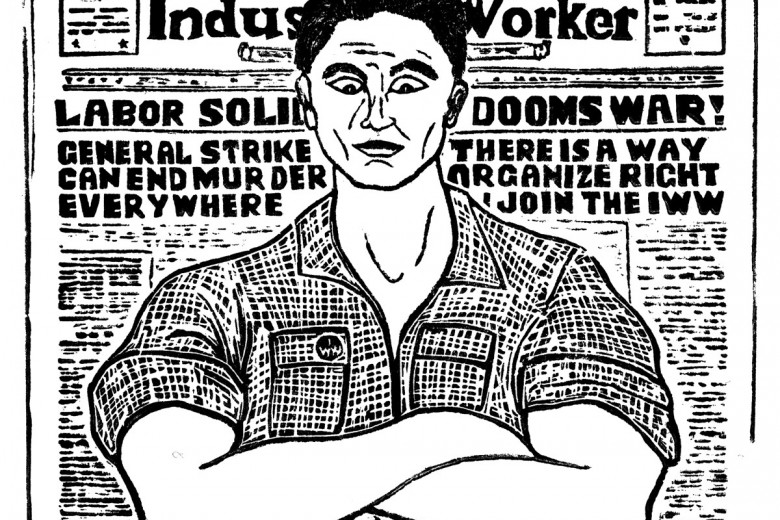

In letting her subjects speak for themselves, Silvera leaves most of the critical work of analysis up to the reader. The understanding is that the women are workers, but since their work is tied to their immigration status and notions of racial and sexual difference, they don’t fit into normative Canadian labour rights organizations.

Revisit this book from over thirty years ago, then, not for a way forward but for its complex composition of how language and silence live, grow, and deform. To look back at a book from over 30 years ago throws into question linear progress, the idea that things get better over time. As Canada supposedly comes back from its right-wing period after Stephen Harper and marches on again toward the myth of its multicultural-humanitarian birthright, put into law by the first Trudeau, it is a germane time to think about the recurring silences in Canada’s diversity experiment.

It has been over a generation since the first edition of Silenced was published. Racialized and feminized labour in Canada remains a material and affective requisite to Canadian political and intimate economies. What’s changed is the landscape of punitive laws. In 2014, the Harper government made living with an employer optional for those under Canada’s Live-In Caregiver Program but it also curbed the number of workers permitted to enter Canada by well over half of entries in recent years. Access to permanent residency remains precarious, and women still face low wages, difficult working conditions, familial alienation, and visas tied to employers. Most recently, Trudeau’s Liberal administration, which has criticized the TFWP for displacing Canadian workers, has made vague promises for reform, but a recent parliamentary committee report includes recommendations that directly contravene their public message.

Reading Silenced all these years later establishes that, no matter the ruling party of the day, the state upholds racialized and sexualized violence in its labour laws.