The past several decades have not been kind to workers, as most of us know only too well. Those making minimum wage are making a penny more in real terms than they were in 1976, union membership continues to fall, and wage growth for most has been anemic – far outstripped by rising productivity. And this is to say nothing about how unfulfilling the jobs that swallow the waking hours of our lives can be. Yet when workers speak out, whether about our own crappy working conditions or the absurd enrichment of those at the top, we’re greeted by a familiar chorus that is often loudest inside our own heads: just be happy that you have a job at all.

For some, the implied culprit in the background of this story is the much poorer worker in the Global South, whether at a maquiladora in Mexico, a sprawling electronics factory in China, or a call centre in India. As Canadian workers have been integrated into a globalized economy, the story goes, they can be kept in check by what happens halfway across the world. Labour discipline isn’t just – or perhaps even mostly – a function of globalization, however. There are many domestic pressures keeping workers in line and the economy unkind.

Take sectors where much of the work has to happen domestically, like off-line retail. No longer assessing items one by one, cashiers now rapidly operate barcode scanners and compete with self-checkout machines. While robots are usually thought to be taking over industrial work, automation is now nearly everywhere. True, automation doesn’t necessarily displace workers in a straightforward way – as U.S. President Barack Obama found out when he suggested ATMs were taking work from bank tellers when in fact the numbers of ATMs and human tellers have risen together – but automation ultimately seeks to reduce the number of workers doing a particular job.

Machines, food, freedom

Beyond retail or manufacturing, consider health care. It wasn’t long ago that hospitals had full kitchens that cooked meals for patients on site. Today, many use pre-processed food made in centralized, industrial facilities, which require less labour overall and less skilled labour in particular. A similar scenario is playing out with hospital laundry services across the country. These changes in the work process have occurred in tandem with privatization, making it easier to slash wages and benefits and break existing union contracts.

Catalina Samson has worked in food preparation at the Vancouver General Hospital for 20 years, first as a public-sector employee and now at Sodexo, a giant food services multinational that has operated the hospital’s kitchens since 2004. Along with the introduction of processed foods, Samson has experienced a more frenetic work pace, more cramped conditions, and ever more menial tasks expected from workers. She confides that her work is less fulfilling than it used to be. “It’s so limited,” she says. “There’s no longer a sense of service quality for patients.”

Ken Robinson knows the feeling all too well. In his role as vice-president of B.C’s Hospital Employees’ Union, he has seen mass deskilling, job loss, and dislocation. Faced with such monumental changes, the union has often been on the defensive, he acknowledges. “At the end of the day, it was about trying to keep a stable work environment,” he says. Automation produces uncertainty, and, under capitalism, this uncertainty has a disciplinary function: it shrinks demands and puts workers back on their heels.

Like Samson, Robinson started out working in a hospital kitchen. He saw his job disappear as food preparation was moved to an industrial kitchen in another city (though one still within the public sector). At the time, he was able to retrain and find alternate work within the hospital, while becoming active in his union. The difference between his experience and Samson’s shows how workers can experience the same process of technological change and automation in different ways, depending on their organizational leverage at the time.

Last year, an influential study from Oxford University calculated that up to 47 per cent of existing jobs in the U.S. are susceptible to automation or computerization in the near future. The jobs most likely to be hit, according to the researchers, are not just low-wage positions in sales and services (think telemarketers) but also many middle-class jobs in office administration (think insurance or tax specialists). Popular new books with titles like The Second Machine Age make gloomy predictions about available work. This rhetoric about an automated threat to jobs dovetails with increasing rancour about the “hollowing out” of the middle class – a fear at the very centre of political discourse in both Canada and the U.S.

Nonetheless, debate rages about the role technology is playing in dramatic changes to labour markets, especially as job growth is increasingly concentrated in low-wage work. The reality is that, while robots take away the need for some skills, the way work is remunerated and distributed depends more on the workings of political economy than computer circuitry. It’s no coincidence that automation and deskilling in the health sector have been accompanied by subcontracting and privatization, creating working conditions that seem more suited to a Tim Hortons or a Burger King than a public institution. Worsening conditions like lower incomes, increased stress, and insecurity create an inertia that has been difficult for unions to counter.

Struggles and fears over automation are as old as capitalism, but they need not be a reaction to technology itself. Indeed, even the infamous Luddites of the first Industrial Revolution are being reclaimed from their misrepresentations in high school textbooks. For the Luddites, the fight was not against technology so much as for worker control over its use. Karl Marx famously saw capitalism as a necessary but impermanent economic system – one that would develop technological and human capacity while at the same time produce its own gravediggers.

Perhaps less famously, in 1930 John Maynard Keynes predicted that the development of technology, combined with the “euthanasia of the rentier,” would lead to a 15-hour work week by the year 2030. Of course, rapid technological change has led neither to Marx’s wish for universal equality and creative freedom beyond capitalism nor to Keynes’ wish for the same under a reformed capitalism. In fact, many of us work more and more for less and less, even as technology advances. How is this possible?

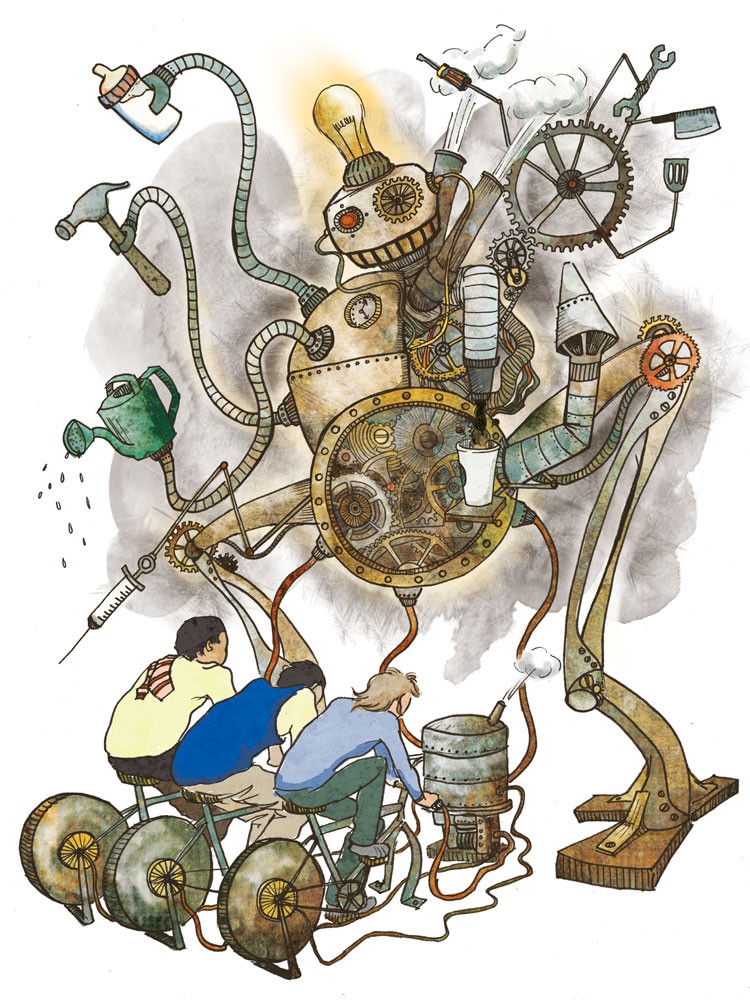

Automation is a potentially liberatory tool like few others, but when bosses and managers oversee its use, deciding what we produce and how we produce it, from iPhones to Humvees, the result is displaced workers who are forced to compete for other waged work rather than being freed up to live more of their lives without a boss.

Competing for care

Robots are not the only ones supposedly coming for your job, especially if your job involves the caring and emotional work that robots and computers can’t deliver. There are other ways to save on labour costs. Production – whether of goods or, increasingly, services – migrates north to south while workers migrate south to north. Much of this migration is highly regimented: rules are designed to keep migrant workers in extremely precarious living and working conditions, while at the same time helping maintain discipline over the entire domestic labour force. As goods move with increased freedom, the movement of people is strictly regulated, forcing economic refugees into precarious and often deadly circumstances like overcrowded boats.

Abelina Morales is just one example of this regulated global flow of human lives. She came to B.C. from the Philippines five years ago under the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP), a specific stream of the Temporary Foreign Workers Program (TFWP). She made the decision to migrate in order to provide a better life for her two children and husband, but the rules of the LCP meant that she was first separated from her family for several years, aside from short annual visits. “I’m a mother,” she says. “My kids are still young, and here I am taking care of my employer’s kids. I give my time and love to kids who aren’t mine.”

Live-in caregivers are tied to a single employer with whom, as the name implies, they live. Not only are they often isolated from others, they have less access to social programs than resident workers and face the risk of being deported at the first sign of trouble. These working conditions create insecurity that manifests itself in different ways. Many caregivers, for example, end up working significant undocumented overtime. Because caregivers effectively live at work, not only are work and life deeply intertwined but fear of retribution makes it hard to refuse employer demands.

Yet while migrants are some of the most precarious workers of all, they are not hapless victims. Jason Foster of Athabasca University has written extensively on the TFWP and migrant labour and reminds us that “these are men and women who are making active choices for themselves, what we can argue are rational choices for themselves.” The former live-in caregivers I interviewed for this story understand themselves to be a source of cheap labour within an unjust institutional structure. They explained they were not “taking jobs” but filling a need created by clear government policy – one that ends up lowering the floor of labour standards.

What’s more, like resident workers, migrants face deskilling, not because of automation but because, when they move, their skills are devalued. Many live-in caregivers were nurses in their home countries. “We’re highly skilled,” says Morales, “but only good enough for being nannies here.” Motivated but deskilled and put in precarious positions, migrant workers are used by policy-makers to mitigate against full employment and the increased bargaining power of workers, especially in low-wage occupations.

Those who blame migrants for “taking jobs” are only helping employers to divide workers. Denying migrant workers residency status and labour rights is particularly odious in light of the fact that the TFWP is, in essence, a capitalist recalibration of Canada’s immigration policy. The “Good enough to work, good enough to stay” slogan adopted by the United Food and Commercial Workers is a good example of a major union pushing back against attempts to use nationality to divide workers.

When unemployment (or underemployment) is low or falling, more migrant workers are “invited” in, especially into low-wage sectors. A program like the TFWP helps give employers the upper hand even in economically good times when workers typically feel empowered to increase their demands.

The threat of full employment

Already in 1943, the economist Michal Kalecki clearly showed how full employment poses a threat to the capitalist order. “Under a regime of permanent full employment, the ‘sack’ would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure,” said Kalecki. “The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow.” Governments and employers learned their lesson about full employment during the postwar boom when labour

was more militant and empowered. Full employment hasn’t seriously been on the policy table ever since.

Understanding the role of labour discipline in the use of automation and migrant labour sharpens the political terrain that can be contested today. Popular ideas about civilizational collapse or salvation – a dystopian or utopian future ushered in by robots and computers – obscure the agency of real workers and the struggles we can lead. Migrant workers, unlike robots, can elicit solidarity and organize in their own interests and in the interests of all workers.

Migrant power is labour power

Migrant workers are mobilizing within their own communities and trying to shift the public debate. Syed Hussan, coordinator of the Toronto-based Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), explains: “Migrant workers are not a new creature; they are racialized immigrants now made temporary under a global push to move to a system of temporary migration.” If this system is part of broader changes in global capitalism, then local xenophobia, while making the lives of migrants worse, will continue to harm all workers.

Hussan says that the first responsibility of organizations like MWAC is to migrant workers themselves. “We have to win things for people in our communities.” Opposing changes to the LCP that would remove caregivers’ pathways to citizenship is a key ongoing struggle. Protecting this feature of the program is critical not only as a defensive measure but because it provides an opening for a campaign to expand such pathways to encompass all migrant workers.

Working within migrant communities is vital but not enough, says Hussan. “We need to reach out to allies, to get people to understand the broad changes, to connect the dots. This is not a national problem but one rooted in global transformations of capitalism.” As an example, remittances are increasingly seen as a form of development aid that can replace more direct forms of investment. Hussan likens the struggle for labour rights and immigration status for migrant workers to struggles against austerity. Neither struggle is limited to one country, and both affect the whole of society rather than small, limited sections.

Organizations like Alberta’s Temporary Foreign Workers Support Coalition are paving the way to making justice for migrant workers a society-wide demand, forging concrete solidarity with local workers. The group has had success organizing information sessions to demystify the TFWP for local workers, protests to generate visibility, and social events to bring migrant and resident workers together. This past Labour Day in Edmonton, they held a large Temporary Foreign Worker Appreciation barbecue that was attended by hundreds. Like MWAC, the coalition organizes around simple demands like “permanent residency now,” both for migrant workers already in Canada and, ultimately, for all migrants. “Being able to outreach with one solid message is key,” says organizer Marco Luciano.

The difficulty, however, lies in breaking through a media and political consensus that often sees migrants as a threat rather than allies on the front lines of global labour struggles. Fear-mongering fostered by racism makes it easier for employers to pit workers against one another. Solidarity, on the other hand, has the potential not only to vastly improve the lives of migrants but also to pull the rug out from under strategies seeking to divide and conquer workers. Demands like immigration status on landing challenge false divisions, acknowledge the agency of migrants, and embrace our shared humanity.

Migrant workers and robots present two sides of the same broken promise: that, given time, we can be free from drudgery and that we can be free together. The authors of the 2013 Oxford study on the effects of automation conclude that “for workers to win the race [with technology] … they will have to acquire creative and social skills.” Workers are human and thus creative and social by nature. Our mission must be to develop our creative and social skills to better stand in solidarity, to organize and win bargaining power, and to dismantle one obstacle at a time, together.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)