Canada’s 1960s: The ironies of identity in a rebellious era

By Brian D. Palmer

University of Toronto Press, 2009

Canada’s 1960s is a magnificent achievement that distills the essence of the political and social upheavals that defined the 1960s in Canada. Palmer sets out to demonstrate that the 1960s transformed Canada in fundamental ways, and does so very convincingly. Canada, as it had previously been understood, “fractured and came apart in the 1960s.” When Canadian identity was put back together again after that rebellious decade, “it bore little resemblance to the Canada that many of the pre-1950 years thought they knew so well.”

Perhaps what had changed most significantly in the political identity of the country was the perception of Canada as a British self-governing Dominion with some subordinate regional and ethnic variations. Waves of non-British post-war immigration, the beginnings of the Quebec independence movement and the rise of a Red Power movement among Aboriginals would powerfully challenge this perception. British decline and the rise of American imperialism further contributed to changing the nature of nationalism in both Canada and Quebec.

Youth and labour in revolt

The revolt of the Québécois and Native peoples overlapped with a generalized revolt among youth, workers, women and the intelligentsia. In many respects youth were at the forefront of all these struggles, as revolutionary politics coincided with a broader transformation of the cultural and political mores of the country.

When many people think of the youth revolt of the 1960s they imagine university students. Palmer, however, demonstrates that youth revolt drew strength from all sectors and was very pronounced among the working class, women and Aboriginal peoples. Demographic changes fuelled this youth surge as the post-War baby boomers poured into the workforce and the educational institutions and, in some areas, swelled the ranks of the unemployed.

Between 1964 and 1966 the country was beset by a tremendous wave of strikes — many of them illegal, and often involving sabotage and violence. About 600,000 workers went on strike between 1964 and 1966. Young workers were at the forefront of most of these struggles, especially the wildcats, which were in defiance of not only capital and the state but the union leadership as well.

At the same time, the union movement underwent a transformation in which economic struggles intersected with nationalist anti-imperialist struggles in both Canada and Quebec. This was the beginning of a process where the “internationals” (American unions with branches in Canada) would eventually lose their dominance in the House of Labour and the broader concerns of social unionism would supersede the narrow interests of business unionism in many labour organizations. Much of the Quebec movement would become overtly socialist and radical-syndicalist for a time.

Palmer ends his chapter on the great labour revolt with speculation on what might have been if the many sectors in revolt had combined their forces. “Around the corner of the wildcat wave of 1965-6 was a growing left challenge. Had it co-joined youth of the university and the unions, the result could well have reconfigured the nature of twentieth-century Canada. Class difference is a difficult hurdle to leap, however, and as campus youth, women, and Aboriginal advocates of “˜Red Power’ joined the unruly workers of the 1960s in an explosive embrace of dissidence and opposition, they did so, ultimately, divided from one another, in separate and unequal mobilizations.”

Multiplying & divided movements

Palmer describes the growth in the 1960s of a predominantly youthful left, emerging with the Combined Universities Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament but soon coalescing around a great variety of organizations, ranging from the relatively narrow Student Union For Peace Action to the much broader Canadian Union of Students. By the mid-1960s, marking the generational shift underway, participants in these groups would be referred to as the “New Left” to distinguish them from the “Old Left” of the CCF/NDP, Communist Party and other formations.

The New Left hit its high-water mark in about 1968, with most organizations disbanded or in the process of disintegration by the end of the decade. Some individuals went in anarchist, anti-Marxist, apolitical or crackpot directions. The more political joined the NDP or the traditional Communists or joined formations with a Maoist or Trotskyist bent. Many made their mark in academia or in progressive organizations not associated with any party. Three broad, often overlapping tendencies emerged, which Palmer identifies as Marxism, left nationalism and feminism.

The left nationalist tendencies that emerged at the end of the decade maintained greater ties with the Old Left, though many individuals with New Left experience would play important roles in movements that emphasized the connections between independence from U.S. economic dominance and socialism. The manifesto For an Independent Socialist Canada, launched by the Waffle movement in 1969, forwarded an anti-imperialist analysis that independence could only be safeguarded by socializing the most important means of production, as only the working class and their allies had a vested interest in Canadian independence. The Waffle would exert considerable influence in the NDP, as well as some influence in trade unions and other institutions.

Feminism predated the 1960s, of course, but there were many new developments during the decade. The decade would witness campaigns including demands for daycare, equal pay for work of equal value, equality in the workplace and other institutions, education around birth control and a campaign against the antiquated abortion laws (which resulted in the first demonstration ever to shut down the House of Commons). Women’s issues became important in many trade unions and influenced both the organized and unorganized working class.

The organized women’s movement won or partially won some of their demands and influenced many institutions. They were strong in the Waffle movement within the NDP, and through them influenced the party as a whole. Feminists, like the broader Left, eventually split into different factions, with the two broad tendencies being the socialist feminists and the radical feminists.

Nations within the state

The struggles of the 1960s were fiercest in Quebec. The class struggle was sharper there and related much more directly to the national struggle than in English Canada. “Quebec’s particular oppression” Palmer writes, “meant that it was in the forefront of both socialist and countercultural challenges to the mainstream of the Canadian nation in the 1960s.”

Palmer entitles his Quebec chapter “Quebec: Revolution Now!” for good reason. There were large numbers of Quebecois who felt that a radical transformation was both necessary and possible, and a small minority who actively worked at what they hoped would be a socialist revolution for national liberation. Palmer does a superb job of analyzing these years of struggle which in nearly all sectors were on a broader and deeper scale than in English Canada. Quebec did not, of course, experience a revolution but did undergo a more far-reaching transformation than anywhere else in North America.

The chapter on Aboriginal struggles is appropriately entitled “The “˜Discovery’ of the “˜Indian.’” It is appropriate because after the dispossession of Canada’s First Nations in the nineteenth century, colonial society accorded them no economic or political rights. On many reserves, residents could not even leave without permission of the Indian agent. Status Indians were not recognized as citizens and could not vote until the early 1960s. The majority of First Nations people lived in deplorable economic and social conditions. Further, the government pursued a program of cultural genocide through prohibition of Aboriginal religious and political traditions in law and the suppression of language and culture through the residential school system. Colonial Canada assumed Aboriginal peoples would simply disappear from history as distinct peoples.

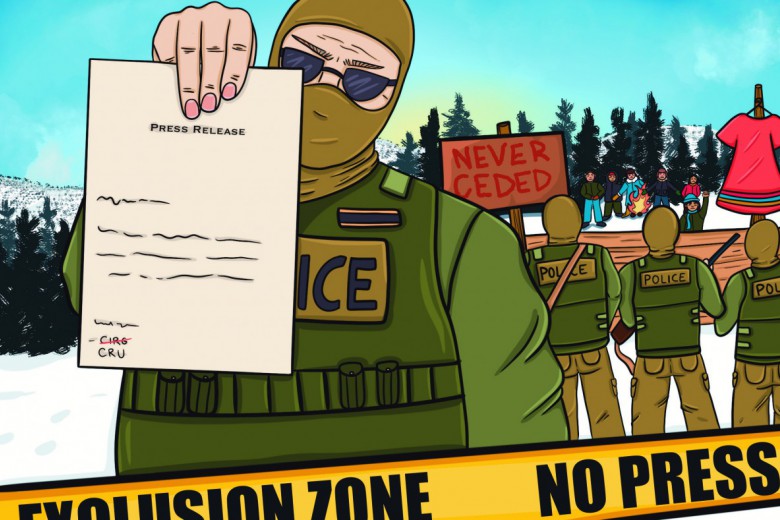

This began to change, however, as Aboriginal populations began to recover in the 1930s from the devastating impacts of the introduction of new diseases. This contributed to renewed struggles for their rights in the 1930s and 1940s. Aboriginal peoples asserted the necessity for treaties to be honoured, and economic, social and cultural rights, as well as Aboriginal title, to be recognized. Some Aboriginal peoples further demanded self-determination. As in other sectors the methods of struggle assumed many forms — petition, negotiation, public demands, political lobbying, and among the more militant, blockades, occupations, civil disobedience and the threat of violent resistance. The state response was varied and ranged from making concessions to co-optation or violent repression. Some progress has been made but many of the problems facing Aboriginal peoples remain unresolved; their struggles continue to this day.

Left legacies

While Palmer is obviously sympathetic to the movements of the day, for the most part he avoids romanticizing them. He takes note of the crude formulations, the anti-intellectualism, the disdain for theory and organization and the naïveté of elements of the New Left. He notes the macho posturing and left adventurism common to elements around the FLQ and other organizations. He quotes Métis radical Howard Adams on the dangers of opportunism and corruption in Aboriginal organizations. Palmer tells it like it was, warts and all.

I would be remiss in not mentioning a few criticisms of Palmer’s book. He could have put more emphasis on the anti-imperialist and class dimensions of the left nationalist movements, many of which were informed by a broadly Marxist analysis. I would argue that the Waffle (and similar tendencies in some trade unions and other sectors) had a more sophisticated class and anti-imperialist analysis than either the preceding New Left tendencies or the Marxist-Leninist groups that succeeded them. This analysis was buttressed by an organizational sophistication that managed to engage a much broader base in progressive politics. The evolution of trade unions in Canada might also have received more attention in the section on workers’ revolts.

A little more on the legacy of the 1960s would also have been useful. I would contend that much of what began in the 1960s bore fruit in the 1970s; this was true among women, labour, Aboriginal peoples, the intelligentsia and artistic communities. Palmer himself is an example of that legacy: he is now editor of Labour/Le Travail and one of Canada’s pre-eminent labour historians — a field of study that barely existed in this country before the 1960s.

But the above are minor criticisms indeed of a work that will be a standard reference for scholars, students and activists for years to come.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)