“I was so loopy from Benadryl that my bedroom buddy, that’s what my husband occasionally calls me, was up all night listening to me talk in my sleep,” says my colleague Kathy, who had taken a strong antihistamine the night before. This is a mundane example of the ways in which colleagues share and take part in one another’s personal lives – through dialogue. Though we may not actually inhabit each other’s personal spaces, we discuss our previous evening every single morning, and every Monday, like clockwork, we talk about our weekends.

Kathy is a very dynamic presence in our office: she is chatty and talks to every-one about what’s going on with them, how their kids are doing, and so on. She teases another worker about her crush on the head of the financial department, playfully pestering the woman about her “boyfriend.” It’s Kathy’s way of tolerating the dreary, daily grind, and it’s also her way of getting close to the people around her.

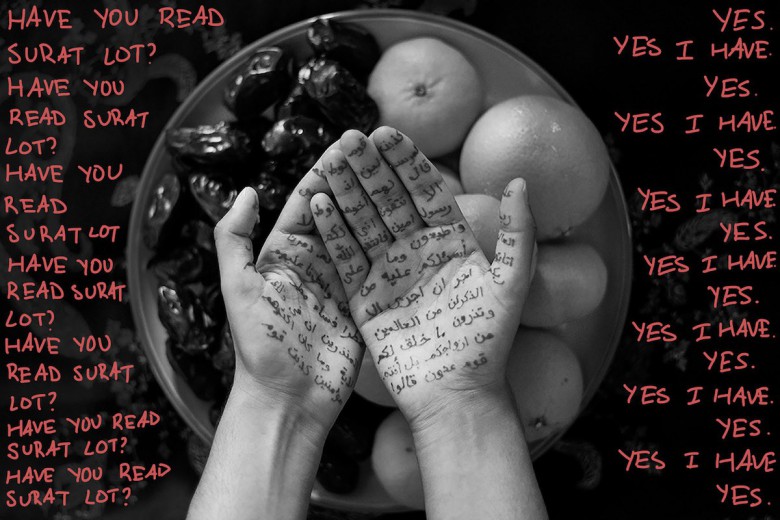

All except for me. I’m queer and because of that, I’m discouraged from speaking about my personal life. So, I limit my anecdotes to the “friends and events” sphere, so long as those friends and events aren’t too gay. This is not intended as a sappy diary entry: I am an empowered queer person, in a decent-paying job at a university that cannot fire me outright for being queer. For the most part, I don’t really feel left out because I don’t care about fitting in. But there are many queer folks who would care; for a variety of reasons, they may want to fit within the system more than I do (there are many LGBTQ individuals who are not necessarily queer politically). Those workers should be able to participate in their work communities in the same ways as their heterosexual colleagues.

It’s hard not to feel exasperated when someone asks me what I did over the weekend; even if I went on a date with a woman about whom I’m excited, I still feel compelled to say, “I didn’t get up to much.” If I speak openly about my experiences or views as a queer woman, Kathy gets quiet, looks displeased, and doesn’t respond. My supervisor has encouraged me to talk to her instead of Kathy about my life, but that strategy simply leaves the problem unaddressed.

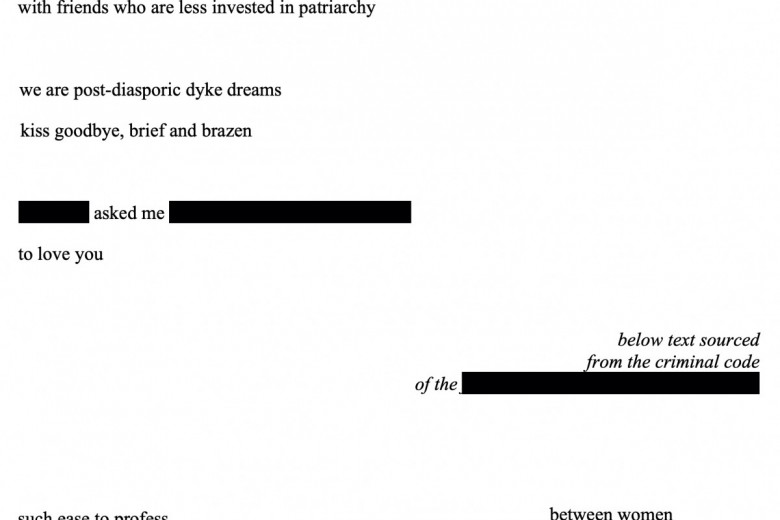

A concern for queers within the labour movement is not only our marginalized status, but the ways in which queerness becomes invisible within the existing discursive frameworks of professional life. I am starting to wonder if employers really understand what “queer support” means. Embracing queerness means affording credibility to non-normative forms of sexuality, gender, and family. Queer support in the workplace must be more than empty words and symbolic policies. It means anti-discrimination training; it means ensuring managers are pro-women, pro-queer, and anti-racist – and that they face professional discipline when they are not; it means tangible initiatives and a strategic framework for queer inclusivity.

The central place of banks and large corporations in Pride celebrations, meanwhile, is a form of appropriation that conceals the apathy and oppression that continues in so many workplaces. Sponsorship and branding is one thing, but have these organizations adopted gender-inclusive language in their policies, forms, and databases? Are they hiring queer and racialized people for managerial and leadership roles, and providing appropriate staff training? Is there a place for queers within unions? If not, they simply do not support queer diversity. Too often, the embrace of Pride celebrations by employers doesn’t translate into tangible gains for queer workers.

We must stop complacently accepting statements of diversity that are more public relations strategy than reality. Perhaps queerness is too fundamentally incompatible with heteronormativity to ever truly thrive within corporate environments. Perhaps we queers must always be deprived of something or must cease to be fully queer if we seek the same job choices others do.

Ironically, when corporations become queer for a day, for a month, or for a business statement, they are differentiating themselves from those who are queer every day of the year. Exercises in queer branding around Pride month invert queer support until it is queers who are supporting employers in their branding efforts. Organizations that have contributed to our grief reap the benefits of their own supportive claims, while queer students and workers, and their lovers and partners, are still denied any significant presence within them.