The co-evolution of people, animals, and trees has always humbled me and made me aware of the ways in which our Earth is a delicately connected, living being. I often think about how my body was meant to thrive in an environment that I no longer belong to and I imagine all of the ways we evolved alongside our ancestral lands – darker skin, intestines that accommodate certain bacteria, stories and myths. Through a symbiosis that imagines a future while necessarily reconstituting our histories and stories, I process how, as an immigrant settler, I can cultivate ethical relationships in general – but most importantly with this land and its trees. How do I bear witness to them, like they do for me?

Reconstitution

This inquiry starts, as many inquiries do, with heartbreak.

In a race to get to know each other, we spent eight hours weaving stories about our pasts while we switched, smoothly holding space and pushing power the way that lovers do. He told me stories of Cairo, of the old shopkeeper with a store full of trinkets, and I tell him about the waterfalls in Kotagala. Both our childhood summers were spent in the concrete buildings of North York and Scarborough, where we bought Jamaican patties after school and went right home. We both only took part in play that was so restricted in landscape that if our minds did not consume novels and TV and each other’s words, if our minds did not imagine more than what they saw, something inside of us would have withered up.

It was early morning when the summer breeze shook the wiigwaasaatig (1) leaves over the sunroof of his navy Corolla. He put his thumb in my mouth and told me to look at him. When I snapped my eyes to his, he whispered, “good little slut.” I loved him for seeing me. Later, under the incandescent lights of a back alley, I would call him the same.

… if he refutes his words, what can I do?

A Kurugu, with greenish legs like millet stalks,

too was there watching the water to hunt slippery eels,

when he made love to me.

(Kabilar, Kuruntokai: An Anthology of Classical Tamil Love Poetry, poem 25)

That was also the November I met the miskwaabiimizh. They are bushes whose delicate red branches stretch to the sky. Skinny and frail-looking, they bend and sway to accommodate the bursts of cold air from the lake. They are the first plants you encounter as you walk in from the water, marking a boundary and acting as interlocutors between two different worlds. Their branches end in clumps of little white berries. I sat beside them and watched the lake kiss the land while I counted rocks and designed a kolam in the sand. In Ceremony, Leslie Marmon Silko writes, “In a world of crickets and wind and cottonwood trees he was almost alive again; he was visible.”

How do I bear witness to them, like they do for me?

Reconstitution, I think, can only happen when you are seen – by other people or animals or the land. As N. Scott Momaday writes in “Man Made of Words,” we have to understand “who and what we are with respect to the earth and sky” in order to understand ourselves as humans. Here, we are all agents in our histories and stories. Here, as Silko says, “all was retained between the sky and the earth.” I sometimes wonder if mundanities like brief encounters between two diasporic lovers, or what happened thousands of kilometres away is somehow “retained.” I wonder if the water, which has circulated the Earth through rivers and oceans and lakes, through Tamil Eelam (2) and Vietnam and Palestine and Kashmir, is a witness to all of us through its consciousness.

Psychic dislocation

Imagine yourself about to start a sprint – adrenaline pumping, body positioned and tense. Just as you’re about to take off, you realize that your body was always just a breath of air. One of the benefits of this non-corporeality is that when you see possessing hands move toward you, you can just disappear. Poof! You’re gone. And when it happens enough, it becomes a power you can exercise at will. Only, eventually, it stops being a power and becomes a pathology.

So, when a past lover calls me a slut and makes me witness him while he witnesses me, he sees and acknowledges my agency in my story. I told him all that happened through staccato words and the way that my body moved, and I didn’t worry about how he managed to read me so accurately until he left.

The first time it happened was when I was six, in the middle of Sri Lanka, by a tea plantation. The teyilai marankal were witnesses. They talk to each other, you know. They must have told the miskwaabiimizh, for they held me so gently.

The first time it happened was when I was six, in the middle of Sri Lanka, by a tea plantation. The teyilai marankal were witnesses.

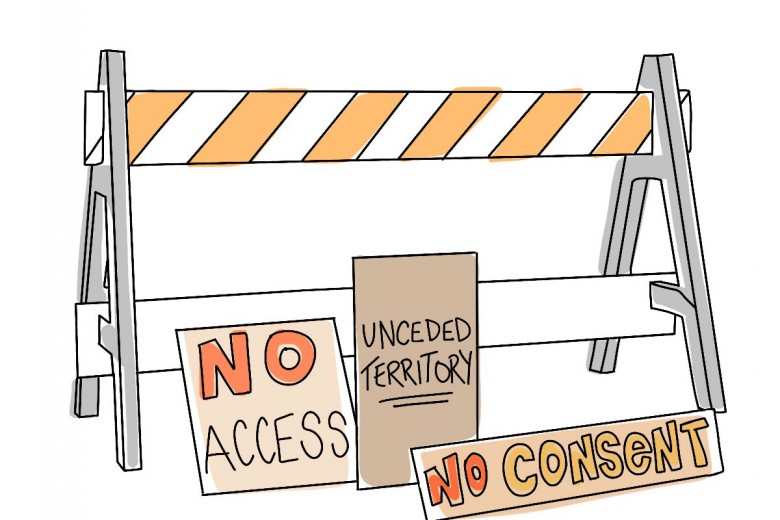

It took me a while to learn the miskwaabiimizh’s name. In the way that I sleuth the internet for my past lovers, I spent hours digging into archives and botany textbooks before coming across Mary Siisip Geniusz’s Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings. I talk to my teachers and friends, and I learn how the miskwaabiimizh’s branches catch dreams for the Potawatomi and how their inner stems are used in tobacco mixes for the Ojibwe. This cosmology of the land continues to be actively buried, but the people who intuitively know this land have oral histories and bodily knowledge that retain these stories in them.

Last week, I explained to my partner why I needed a seasonal affective disorder lamp in the winter months. I told him it was because “I don’t belong here,” and immediately, I felt guilty – like somehow I broke the promise I made to the miskwaabiimizh, or the mitigomizh in the woods near my apartment who watch me run at night. What I really meant was: I’m new here. I’m still learning how to take care of myself and this corner of the world. Currently, I dance around this land like a friendly stranger, sometimes stepping on its toes, creating unintended slights, wanting to compromise and accommodate, but not quite educated in its histories or stories.

This cosmology of the land continues to be actively buried, but the people who intuitively know this land have oral histories and bodily knowledge that retain these stories in them.

The post-industrial settler society we live in has tried to convince me that we’re not interwoven with the land and with each other. In the words of Momaday, we’re psychically dislocated. I think I can assert dominance over this land and others, choose when to be in relation to them, compartmentalize and repress my need for them and their need for me. Resisting this narrative and thwarting my settler-assimilation, Qwo-Li Driskill draws from generations of Indigenous writers to carefully illustrate the possibility of erotic and mutually generative relationships with the land and each other. In “Stolen from Our Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a Sovereign Erotic,” s/he quotes Craig Womack’s Drowning in Fire: “I dreamed that I came back a year later with him and the pond was no longer there, only a large, shimmering mud flat... In the dried-up creekbed, at the exact spot where Jimmy had come in the creek, had grown a red cedar. My Aunt Lucy stepped out from behind it, and she laughed at the way she’d startled us. ‘See, boys,’ she said, nodding at the cedar, ‘now you know where those trees come from.’”

Displaced (racial) memory

Two days ago, in the middle of the night, I saw an apparition: dark blue waves against the jagged rocks of Trincomalee. I breathed in the smell of salt water and heard the undulating rush and crash of the ocean. I hung suspended above as my seven-year-old self climbed the crooked rocks while the waves tried to lap at her ankles. The images appeared interspersed with memories and narratives of my past lover, who told me, very reasonably, “I wish I had never met you.” I felt an indiscrete longing for them, unmoored from reality.

Racial memory can invoke a biological essentialism, which limits identity to colonially defined biological markers, like blood quantum. To move beyond this essentialism, I believe it is necessary to trace the ways in which identity extends beyond blood, through ancestral narratives and, more importantly, through resistance against settler states. My own racial memory repeatedly manifests in my complex relationship with the land.

To move beyond this essentialism, I believe it is necessary to trace the ways in which identity extends beyond blood, through ancestral narratives and, more importantly, through resistance against settler states.

To me, this memory is a lived affective and bodily experience mediated by the land. Along those lines, my displacement is a state of being away from the land while that racial memory persists in my body. As a forcibly displaced person, this memory also exists through stories, which are told out of context. For example, when my mother gives me life lessons – how to tell when to pluck a mangai, how to swing on the branches of an alamaram, how to make paste from veppa illai, how to clean dried nethili – they exist as unevolving, calcified ritual. I have no interaction with the stories or the land she talks about; they may as well be fantasies. These are fantasies about my imagined ancestors and the people who lived in Tamil Eelam, people who used panai marankal as fences, woven plates, and roofing; who lived with the ocean, took from it and gave to it through prayer.

This knowledge, these memories and narratives, are stunted in my body and coloured with recent violence and multiple colonial traumas. My mother was in Sri Lanka last year, and in a poignant literal-symbol, she tells me about the “headless” panai marankal, whose heads got in the way of bombs in 2009. How painful is it to keep racial memory alive about a lost relationship to the land? My reflections became more complicated in light of my new-found knowledge that the Tamil-Sinhala war erased narratives of the Vedda people who lived in Sri Lanka and Tamil Eelam since before 500 BCE, whose lives have been pushed onto ever-shrinking reservations.

I wonder whether my latent memory will reawaken into action if I am ever able to go back to Eelam – whether it is even my place to go back, or whether it is now necessary to start evolving narratively, to reject biological essentialism, learn the necessary histories and stories of this land, and become an accomplice against capitalist-settler forces.

A renegotiated racial memory of lovers and land

He leaves me soon after I tell him I love him (too soon). He disappears abruptly, and I wonder how much of myself I’ve projected on to him. How much of these narratives are fantasy – whether I orientalized or self-aggrandized; whether my intuition with him, with the miskwaabiimizh, or with every tree I ever met was all wrong.

My connection with lovers and the land feels like it is about me. I feel like an explorer who projects my narratives onto some terra nullius. I wonder, in my displacement and psychic dislocation, whether I can be in long-term, everyday relationships with anyone or anything where I centre them, their histories and stories.

Currently, I dance around this land like a friendly stranger, sometimes stepping on its toes, creating unintended slights, wanting to compromise and accommodate, but not quite educated in its histories or stories.

I think I have to keep trying. I have to let lovers and the land mediate our co-evolution and let them alter me in irrevocable ways, whether it is narratively, through histories and stories and lessons, or bodily, through affective and visceral intuition. I have to hold them in the ways that I know: by sitting with their subjectivity, politicizing my relationship with them, and giving them space to be. I hope, like Momaday writes, that “it is possible to formulate an ethical idea of the land – a notion of what is and what must be in our daily lives” even as a displaced person.

So, this time around, as I sit with the miskwaabiimizh, I look at them differently. This land exists outside of my projections and will continue to exist long after me. I acknowledge that I need this relationship to exist and I am profoundly grateful for everything it gives me. Hundreds of miskwaabiimizh grow in a bush along the sand, creating a sort of fence a few feet from the water. The red of the miskwaabiimizh contrasts strongly with the white sand, which leads to a blue, expansive lake. This landscape is adaptive and intelligent. It is different from Tamil Eelam. It needs to be, because the weather, the sand, the water, the people, and our interaction with it, depend on one another to create a unique place.

(1) I use Ojibwe names because that is what I had access to. There are layered histories in what is currently known as southern Ontario that I’m not yet aware of, but will try to learn more about.

(2) Tamil Eelam is a land located north and east of what is now called Sri Lanka. It is a fraught landscape, one whose identity has been shaped by a polarizing civil war, which officially began in 1982 and ended in 2009. The land continues to be encroached upon and “settled” by the Sri Lankan government. Tamil Eelam identity homogenized Tamil identity on the island through violent acts for the purpose of strategic, political essentialism, and therefore it is a term I use cautiously, with full acknowledgement that not all Thamizh people who reside in this location identify it as such.

This essay was the winner of the creative non-fiction category of our ninth annual Writing in the Margins contest. Creative non-fiction entries were judged by Joshua Whitehead. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Regina Public Interest Research Group (RPIRG) for this year’s contest. Briarpatch will be accepting entries for the tenth Writing in the Margins contest in September 2020.