The Wet’suwet’en system of hereditary government remains in place, as it has for more than 10,000 years. But if you talked to the Canadian government or TC Energy – the company currently forcing a pipeline through Wet’suwet’en lands – you would never know it.

Canada and its resource extraction companies have been on a centuries-long campaign to eradicate Indigenous hereditary leadership and replace it with municipal-style governments. Today, gaining “Indigenous consent” is fast becoming a vital component of industrial projects in so-called Canada – to placate the courts, but mostly to keep the public’s support in an age of “reconciliation.” But the question of who can give consent on behalf of an Indigenous community and its territory is hotly contested.

The structure of tradition

The bahlat, Wet’suwet’en for “feast hall,” is the hub around which Wet’suwet’en culture and governance revolves. For a decision to become law, it needs to be communicated in the Witsuwit’en language and affirmed orally in a bahlat by the House Chiefs (called Dini ze’) and house group members. In bahlats, traditional names are passed from one generation to the next; business is conducted; and, most importantly, people learn how they can fulfill their role in their house. Decisions are made carefully and with great consideration for their potential outcome. Others, even those from outside the Wet’suwet’en community, can share information or join discussions about a topic, but a Dini ze’ has final say over what transpires on their house’s territory.

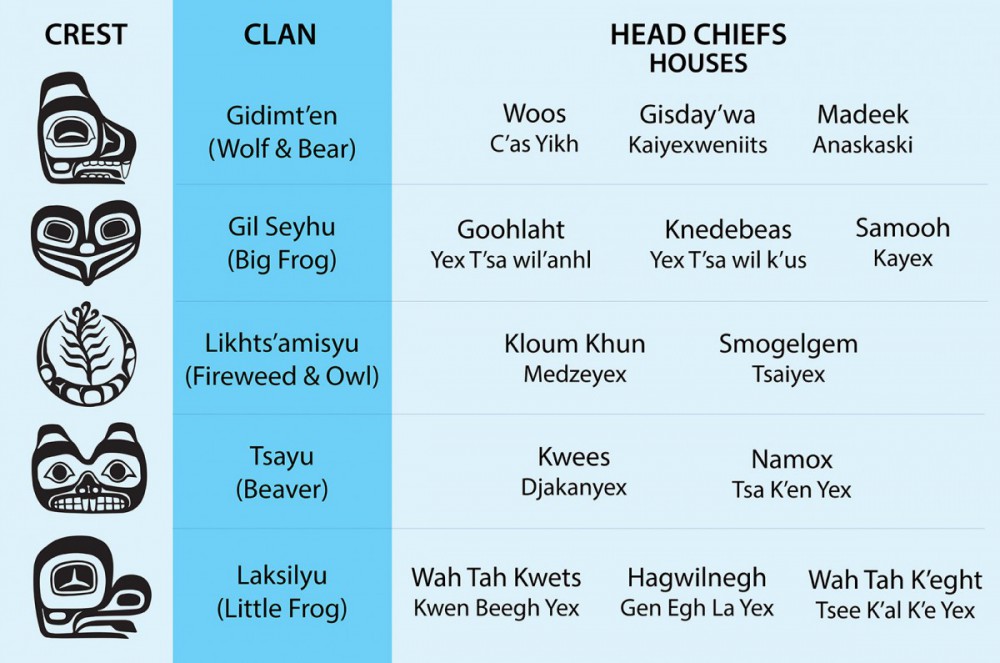

There are five Clans and 13 house groups within those Clans. Each house group has a Dini ze’, and four house groups currently have vacant Dini ze’ seats. Dini ze’ of each house group are responsible for the people and territory attached to the names they hold.

Hereditary names are created when a great event occurs on a specific part of the yintah – meaning that the power of hereditary names comes from the land. The story of the event is often made into a song, which is sung in the feast hall. A name is passed on to another member of the house – based on their integrity and character – when the previous holder of the name dies.

New names can be created, but it rarely happens with names as big as Dini ze’. Gidimt’en checkpoint spokesperson Molly Wickham’s name, Sleydo’, is new, but it’s a name for a relatively small position. Sleydo’ received the name in recognition of her work for the Gidimt’en Clan and the nation as a whole.

The strong value placed on permission is part of the reason the Wet’suwet’en repeatedly stand in the way of projects, like the Northern Gateway and Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipelines, that move forward without obtaining proper consent.

The land is the basis of Wet’suwet’en life. Wet’suwet’en yintah is 22,000 square kilometres, and the territory is abutted by the lands of the Tsimshian, Haisla, Gitxsan, Dakelh, and Sekani Nations. Prior to colonization the Wet’suwet’en and their neighbouring nations were highly interconnected. The borders between territories fluctuated as battles occurred and land was ceded and regained over millennia. Trespassing laws, even within a nation’s own territory, were such that if one was caught taking food from anyone else’s territory without permission, the penalty was likely death. Obtaining permission from a Chief to set foot on their territory has always been part of how nations in the northwest of what is now called British Columbia have kept their people safe and managed their resources. These internal structures and the strong value placed on permission is part of the reason the Wet’suwet’en repeatedly stand in the way of projects, like the Northern Gateway and Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipelines, that move forward without obtaining proper consent.

The importance of wiggus

In 2014, Sleydo’ moved with her family onto C’as Yikh, the yintah of the C’as Yikh Clan. She was inspired by members of the Unist’ot’en Clan, who began reoccupying their lands in 2010 in order to stop the now-defeated Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline. “The instructions [for Sleydo’] to be on the land came from me,” Dini ze’ Woos tells Briarpatch over the phone from his home in Burns Lake. Woos is the Chief of the C’as Yihk (Grizzly) House of the Gidimt’en (Wolf and Bear) Clan

C’as Yikh is the territory that the RCMP’s paramilitary force invaded in January 2019. In July 2019, a wooden gate was constructed near the 44-kilometre mark on the Morice River Forest Service Road near Houston, B.C., to block CGL workers from returning to work after Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs evicted CGL. CGL was granted an injunction by the B.C. Supreme Court to remove the barrier so workers could return. The RCMP were ordered to enforce the injunction, which sparked a standoff in February 2020 that captured national and international attention.

Woos was, in part, raised on the land and has not let his years at the Catholic-run Lejac Residential School get in the way of his ability to live as traditionally as he can. It is the teachings Woos received from his family and other Wet’suwet’en that guide his actions in a respectful way – which Woos admits has been a learning process. “It’s all respect,” he says – or, in Witsuwit’en, “wiggus.”

“It’s bred into us from when we are young. That wiggus is still with us,” he adds. “My father told me this: ‘Do not laugh at people. Do not get people to fight with one another. Do not get into quarrels that are not necessary. Otherwise, you’re gonna put me to shame even though I’m no longer around.’”

Canada and the RCMP have yet to display wiggus for the Wet’suwet’en People, Woos says. “They don’t understand us. They don’t understand our connection with the land, our language, or our cultural ways.”

Who consents?

Canadian governments and TC Energy have avoided dealing with the hereditary system while trying to get the CGL pipeline built. But they still need some Indigenous leaders to give consent for the pipeline to go ahead, especially when the pipeline is being built on unceded land.

As the Yellowhead Institute’s Land Back Red Paper notes, “Supreme Court cases Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004; Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director), 2004; and Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), 2005 … established that the federal and provincial governments have a duty to engage with First Nations when their established or asserted constitutional or treaty rights may be impacted by government actions.” In the same vein, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) – which was voted into law in B.C. – enshrines Indigenous people’s right to free, prior, and informed consent to any “legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.”

But who they need to obtain consent from – and who is considered a legitimate authority to speak on behalf of an Indigenous community – is a matter of dispute.

“They’re an imposed puppet government put in place to serve Canada. Every two years you get a new council put in. It’s really hard for them to put something together that has any significance.”

Governments and corporations tend to prefer consulting with band councils, which are often more likely than Hereditary Chiefs to give resource extraction a green light. These councils – composed of a Chief and councillors – are elected by an Indigenous community called a band (or more commonly, a First Nation). A band usually holds and governs reserve land, and band members can live on or off reserve. Band offices receive funding from federal government departments to run programs, operate schools, and maintain roads. Band offices were first created in the 1876 Indian Act, and at the time the government aimed to assimilate Indigenous people by imposing municipal-style governments while extinguishing Indigenous culture.

Dsta’hyl, Wing Chief of the Tsaiyex (Sun House) of the Likhts’amisyu (Fireweed and Owl) Clan, doesn’t mince words about band councils. “They’re an imposed puppet government put in place to serve Canada,” he says over the phone. “Every two years you get a new council put in. It’s really hard for them to put something together that has any significance.”

Band offices, which Dsta’hyl views as municipal governments, provide jobs on reserves, but there are also drawbacks to relying on government-directed programs, he says. “[Canada] forced First Nations into an entitlement situation across the country with the Indian Act. Promises, promises, promises and always a shortfall. Always a shortfall. This enabled them to be able to exploit all of the resources off of our territory.”

“The more they can drive a wedge between municipal [band] governments and hereditary governments, the more comfortable the federal and provincial governments are carrying on with business as usual.”

And when the Canadian government and industry consults with band councils instead of hereditary leadership, it’s a deliberate choice. CGL has claimed unanimous Indigenous support for the pipeline, due to signing benefit agreements with 20 band councils along the CGL pipeline route. But the councils’ reserve lands are a fraction of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs’ 22,000 square kilometres of unceded traditional territory, which includes land where the pipeline would be built.

Several families within the Wet’suwet’en Nation have members employed by band office programs, but they are also part of the hereditary system and have a place in bahlat. “The more they can drive a wedge between municipal [band] governments and hereditary governments, the more comfortable the federal and provincial governments are carrying on with business as usual,” says Dsta’hyl.

“These are problems that we’ve been faced with for the last hundred years or so and we don’t expect them to go away soon. Resistance has been here since contact,” he continues. “Our people and our Chiefs have always known that we are being treated unfairly by being pushed off our own land.”

Who’s behind the Wet’suwet’en Matrilineal Coalition?

Since signing agreements with band councils didn’t quash dissent, the government and industry tried to create and legitimize external groups to consult with, like the Wet’suwet’en Matrilineal Coalition (WMC).

The WMC came to life in 2015, as a joint project between CGL, the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, and the WMC’s three founding members. CGL and the provincial government each kicked in $60,000 in funding for the WMC. The money went to developing a website, a social media presence, and running workshops for Wet’suwet’en people to “discuss decision-making processes for economic development opportunities, specifically natural gas development.”

The WMC project description and proposal was obtained via a freedom-of-information request and shared with Briarpatch. Aside from “establish website for ease of information sharing,” the project description bullet points read as duties already existing in the Wet’suwet’en hereditary system.

In her speech, Tait-Day said the only way for Indigenous people to climb out of poverty is to hold an equity stake in projects occurring on their territories, pointing to the Haisla as an example for others to follow.

The WMC’s founding members, Darlene Glaim, Gloria George, and Theresa Tait-Day, once held Dini ze’ names: Woos, Smogelgem, and Wi’hali’iyte. Each were stripped of their Dini ze’ names in a feast hall for different reasons. Regardless, each remains part of the hereditary system and can voice concerns in the bahlat should they choose. (Tait-Day was banned from attending bahlat, so she needs to hold a feast to make amends prior to being allowed back in the hall.)

In 2016, a Haida clan similarly stripped two Hereditary Chiefs of their titles after they were found to have secretly supported the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline. And before that, members of the Gitxsan Nation seized the office of Elmer Derrick for eight months, after he became the first Hereditary Chief to support the same pipeline.

In early 2019, Tait-Day spoke at a gala event attended by industry and government in Ottawa. She was there on behalf of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition, a group that provides support for First Nations participating in resource extraction projects. The gala occurred a month after RCMP raided the Unist’ot’en checkpoint on Wet’suwet’en territory. In her speech, Tait-Day said the only way for Indigenous people to climb out of poverty is to hold an equity stake in projects occurring on their territories, pointing to the Haisla as an example for others to follow. The Haisla Chief and councillors took their Hereditary Chiefs to court for libel in 2007, and since winning the suit have operated unilaterally out of the band office – which gives credence to the tactic on paper but does not extinguish hereditary rights or title.

Negotiating for jurisdiction

In late February, the federal and provincial B.C. governments and the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs created a memorandum of understanding (MOU), with the WMC permitted to sit in for part of the negotiations. The CBC billed the MOU as an agreement that “outlines steps for transferring control of territory to traditional leadership,” and the agreement does affirm that “Canada and British Columbia (B.C.) recognize that Wet’suwet’en rights and title are held by Wet’suwet’en Houses under their system of governance.”

But as Mohawk policy analyst Russ Diabo writes, the language in the MOU “is an indicator that the Crown governments will take a narrow legal position in the negotiations,” limiting what Wet’suwet’en title and rights will be “recognized” in the final agreement, and holding the right to veto the whole process.

“The signal the federal Deputy Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations sent to the Parliamentary Committee was that the Wet’suwet’en MOU will be subject to the same policy framework for negotiations, as all other Indigenous (First Nations, M[é]tis[,] Inuit) groups are facing across the country.”

As Diabo writes, the outcome hinges on how the Canadian government will interpret the 1997 Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa Supreme Court decision, and they seem to be insisting that the landmark decision gave the Wet’suwet’en only “potential” – not definite or established – Aboriginal Title over their yintah. On March 10, Carolyn Bennett, minister of Crown-Indigenous relations, told the standing committee on Indigenous and northern affairs, “We need to be clear that the [Supreme] Court did not, at that time, grant title to their lands.”

“I believe that this arrangement with the Wet’suwet’en people will now be able to breathe life into the Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa decision so that future generations do not have to face conflicts like the one that they face today,” Bennett added.

“The signal the federal Deputy Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations sent to the Parliamentary Committee was that the Wet’suwet’en MOU will be subject to the same policy framework for negotiations, as all other Indigenous (First Nations, M[é]tis[,] Inuit) groups are facing across the country,” Diabo writes – a framework under which First Nations “will end up as ethnic municipalities, with their reserve lands converted into private property and their rights to the overwhelming bulk of their traditional territories extinguished in perpetuity.”

Signed before the Canada-wide lockdown as a result of COVID, the MOU set a timeline of three months to negotiate an affirmation agreement for Wet’suwet’en rights and title – a period that would have ended on August 14, 2020.

The jurisdiction of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs is at the core of the MOU, but what that means on the ground will depend on Canada’s willingness to listen to the Hereditary Chiefs.

Signed before the Canada-wide lockdown as a result of COVID, the MOU set a timeline of three months to negotiate an affirmation agreement for Wet’suwet’en rights and title – a period that would have ended on August 14, 2020. But at the time of writing, negotiations are ongoing, with a new goal to reach a negotiators’ understanding by mid-October. The MOU, furthermore, doesn’t address the CGL pipeline or RCMP presence in Wet’suwet’en territory.

Future of the yintah

“When the MOU came about and the government started pushing for it we were like, ‘Okay, you need us more than we need you.’ That’s the bottom line,” Woos explains.

Money isn’t vital for revitalization to happen, he says, and Dsta’hyl agrees. “What we’re doing with the whole decolonization process is moving people back onto the land [and] showing [government] what reconciliation looks like on the ground,” says Dsta’hyl. “It’s really important to us to continue building communities out on the territory.”

In 2019, a smokehouse, cabin, and checkpoint were built on Gidimt’en territory, following instructions from Woos. On Likhts’amisyu yintah, where a previous village used to be, members are building a new cabin, kitchen, and dining and bunkhouses, all at the behest of Likhts’amisyu Hereditary Chiefs.

"The reason we speak in our language to fellow Hereditary Chiefs is we talk about all that our ancestors left behind. We talk about all the instructions, traditional ways, cultural ways left behind by those ahead of us.”

“We’re revitalizing, we’re finally restoring our traditional ways out there on the land,” says Woos.

Woos feels the inability of the Wet’suwet’en and the Canadian government to communicate comes down to the spirit of the languages themselves. “The English language and the way we communicate with it is not us. It creates a total misconception. It makes people compete with each other and makes people think of a hierarchy,” he says. “[Wet’suwet’en people] are not like that. We speak the truth in our language. The reason we speak in our language to fellow Hereditary Chiefs is we talk about all that our ancestors left behind. We talk about all the instructions, traditional ways, cultural ways left behind by those ahead of us.”

As optimistic as Dsta’hyl is about the future of his Nation, he isn’t willing to wait for any other government to say what he can or can’t do on Wet’suwet’en yintah. “It took us this long for the word ‘title’ to roll off the provincial and federal government’s tongue. Right up to now they were in complete denial. We’re in quite a dilemma as to how we forge ahead considering all the roadblocks the government has been putting in front of us.”

"We are going to require free, informed consent before any industry or government moves ahead on our territories."

CGL employees, escorted by armed RCMP officers, posted a notice on Woos’ smokehouse on C’as Yikh, stating the structure will be torn down because it’s in the path of CGL’s right of way. More recently, on Canada Day 2020, a convoy of vehicles from Gitxsan territory to Witset was met with RCMP, despite the convoy being on reserve and only peacefully making speeches and singing songs.

The Wet’suwet’en continue to demand that the RCMP vacate the yintah, Dsta’hyl says. “That’s always going to be up front and centre. We are going to require free, informed consent before any industry or government moves ahead on our territories. The pipeline wasn’t even in place and they called it an ‘essential service’ without even talking to us. It’s a pretty sad state of affairs when they claim rule of law is the highest priority. When they can’t even follow their own law, there is no law,” he added.

This story was financially supported by a bursary from the Journalists for Human Rights’ Indigenous Reporters Program.