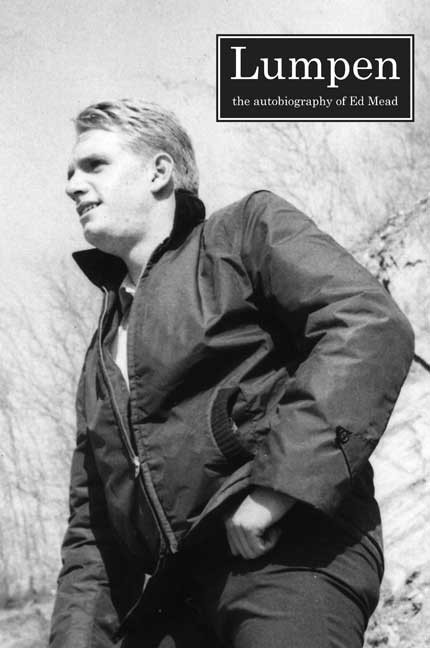

Lumpen: The Autobiography of Ed Mead

By Ed Mead

Kersplebedeb, 2015

Ed Mead’s autobiography, Lumpen, tells a story of a revolutionary life. Mead writes openly and unflinchingly about his days as a social prisoner, his time in the underground George Jackson Brigade, and his work as a prison organizer and founder of Men Against Sexism. The title, Lumpen, refers to Marx’s term lumpenproletariat – a social underclass of gangsters, swindlers, and petty criminals who, Marx argued, had no revolutionary potential; Mead sets out to prove Marx wrong about the lumpenproletariat’s contributions to social justice and revolution.

Mead was born into poverty in California in 1941. His parents split up when he was young, and he spent his childhood moving around the U.S., wherever his mother thought they could scrape out a living. Eventually, they settled in Alaska, where Mead spent his teen years. These unstable and difficult circumstances in his formative years led to a lifetime of recurrent incarceration. In prison, he became politicized.

But this is not a revolutionary’s fairy tale of self-aggrandizement, and it’s clear that Mead is less interested in making himself look good than in giving a frank recounting of a life from which others can learn.

As a young man, Mead spent much of his time behind bars, serving time both for crimes of poverty and for crimes he never committed. His encounters with the law were numerous: a case of burglary here and there, an arrest for a robbery he didn’t commit, a stint in jail for “vagrancy” after Grade 9 because he had no place to live.

Mead developed his political awareness inside the prison system, becoming a jailhouse lawyer to fight his own criminal charges. In a page-turning section of Lumpen, he retells his story of being thrown into prison for a variety of crimes, and being released years early due to a bureaucratic error. His experiences of the arbitrary nature of the court system launched his anti-prison, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist activism.

Finally out of prison in the mid-1970s, Mead co-founded the Seattle-based George Jackson Brigade, a seven-member underground revolutionary group named after the Black Panther member. In solidarity with prisoner, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist struggles, the Brigade staged dozens of bank robberies (“expropriations”) and bombings against government and corporate targets, including the Washington Department of Corrections, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the FBI. An armed group, the Brigade adhered to George Jackson’s praxis, which called for revolutionary activism to carry with it the threat of revolutionary violence.

The group had mixed-class backgrounds; most members of the group were queer, roughly half were women. Historian Daniel Burton-Rose notes, “In a period when the movement (anti-imperialist, prisoners’ rights, feminist and queer liberation) was dividing along political, racial and gender lines, the George Jackson Brigade was striking for its diversity.”

The bombings and armed actions aimed to target institutions and systems of violence, not individuals – though this distinction would, in the case of one bombing, become blurred. During a labour dispute involving grocery chain Safeway, the Brigade set off a bomb at a Safeway store during business hours. Their warning call didn’t go as planned, and the explosion injured a number of customers, after which they issued a public apology (an unusual step for an armed group). Mead was again imprisoned after a bank robbery gone wrong that ended with two other members of the Brigade being shot.

Though the George Jackson Brigade represents one of the most famous aspects of Mead’s organizing, his book is surprisingly brief on the topic. Mead focuses instead on the trajectory of his life in prison, where he spearheaded organizing to defend prisoners’ civil rights. In an environment where sexual violence and homophobia are rampant, Mead founded a group called Men Against Sexism to combat misogyny, homophobia, and rape gangs. Men Against Sexism members produced a magazine against rape culture, held film screenings, and dressed in drag to protest a homophobic preacher.

The work that Mead did, both inside and outside of prison, remains of enduring importance, and there is a great deal we can learn from the struggles in which he engaged, not least from the debate about the use of revolutionary violence to protest systemic violence.

Despite Marx’s dismissive attitude toward the lumpenproletariat, Mead became a Marxist while in prison. In the book, Mead encourages other prisoners to spend time studying Marx’s philosophy, “the science of revolution.” Mead quotes Mao’s more nuanced attitude toward the lumpen: “Brave fighters but apt to be destructive, they can become a revolutionary force if given proper guidance.” Mead, in the end, argues that such guidance comes from dialogue and the study of revolution.

Lumpen is more about the history of action than the analysis of it. While Mead occasionally takes a few pages to discuss why he did something, the politics are mostly woven in with the narrative. The result is a book that draws in readers, gives insight into Mead’s thinking, and offers useful political lessons for people engaged in all kinds of struggles.

Furthermore, Mead’s autobiography tells a story that has in some ways been overshadowed. I can find stacks of books about the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground, but few histories have been written about the cross-class, feminist, and mostly queer George Jackson Brigade. What’s more, most political histories are written by professors, not by poor kids who grew up to be prisoner–revolutionaries. As a grassroots account of prison struggles, cross-movement solidarity, and revolutionary history, Mead’s story in Lumpen is one that needed to be written, and one that deserves to be read.