The relation between sensuousness – having a body – and politics is so primary, so basic, it can seem too close for language to grasp. The scales of a fish do not lean out to touch the water; they are engulfed from the beginning. So it is with bodies and power.

I once asked a partner what percentage of women she thought had not struggled with body image issues. She said, “Zero. Zero per cent.”

Bodies are deliciously, inescapably, painfully social things. They are the source of all we know, but it is only through horror and violence that people try to make them all that we are.

“Trannies” and “drag queens” are still the butt of jokes in so many places where slurs are just the light touch of systematic dehumanization and assault, murder, and suicide are masculinity’s edge.

Someone I loved once taught me that her anorexia had been a kind of hunger strike against patriarchy: a daughter’s assertion of sovereignty in a body whose relationality was a nightmare, a girl with nowhere safe in her own home.

From disordered eating to lack of appropriate health care, from Indigenous incarceration rates to a transgender suicide rate that is 10 to 25 times the average, everything we care about when we think about social justice relates to our bodies: how they are defined and governed and by whom.

As we go to press, Bill 171 has just passed into law in Saskatchewan, amending the Human Rights Code to include gender identity. This follows years of campaigning by transgender activists and their allies in the province.

“There are illegitimate operations of power,” says Judith Butler, “that attempt to restrict our idea of what gender might be, for example in the areas of medicine, law, psychiatry, social policy, immigration policy, or the policies against violence.”

On December 9, the hosts of the radio program Gender Talk Saskatchewan responded to the amendment of the Human Rights Code in a Facebook post: “Today is the first full day that transgender citizens are recognized as fully human before the Government of Saskatchewan. Truly a momentous occasion and a reason to celebrate. Now, if we could just get medical care like the rest of the humans around here!”

“How does a body survive?” asks Butler. “What is a flourishing body? What does it need to flourish in the world?” It’s a social question with a social answer. The body, she says, “needs to be nourished, to be touched, to be in social settings of interdependence, to have certain expressive and creative capacities, to be protected from violence, and to have its life sustained in a material sense.”

Earlier in December, just weeks before the second anniversary of Idle No More, the federal Justice Department released a report finding that the number of Indigenous women locked up in federal institutions grew a staggering 97 per cent between 2002 and 2012. Meanwhile, U.S. cities are in the midst of an unprecedented wave of tactically bold mass protests in response to the non-indictment of the white police officers who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner, both unarmed black men. Young black activists, often led by women, are bypassing the old Civil Rights leadership and using social media communications to coordinate shutdowns of thoroughfares and bridges from Oakland to New York City.

Incited by the Twitter hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #ShutItDown, the audacity of the protests – placing tender flesh and blood in the path of the steel and gasoline of America’s indomitable vehicle traffic and militarized police – testifies to the powerful relays that can form between social media and embodied resistance. As the entire edifice of the white-supremacist U.S. justice system faces a crisis of legitimacy that is long overdue, I hope we can look forward to such a reckoning for Canada’s apparatuses of oppression in 2015. Such a reckoning seems well under way in the resurgent feminist discourse (e.g., #BeenRapedNeverReported) that has arisen in response to revelations of CBC broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi’s violent misogyny.

We can never cast off white supremacy or sexual violence by force of personal will, but when we open ourselves to the stories and struggles of others, we form countercurrents capable of reshaping the world, opening up new possibilities and glimpses of the people we might become.

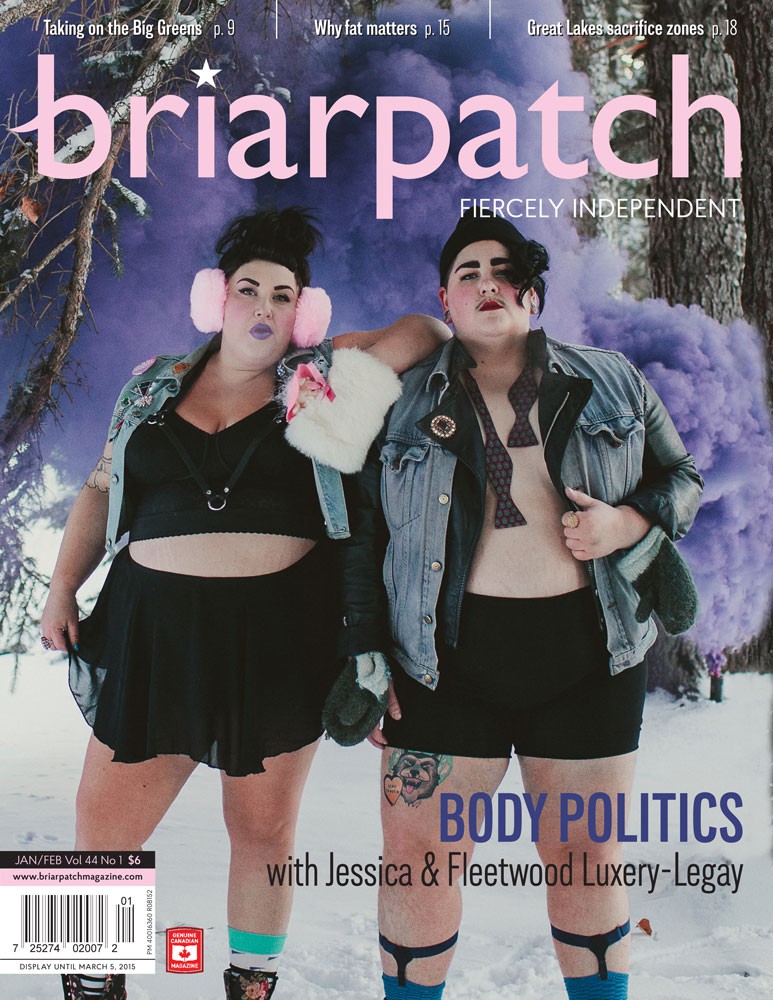

Note: When Jessica and Fleetwood Luxery-Legay met up with photographer Allison Seto in Calgary for their outdoor Briarpatch cover photo shoot on Nov 29, the temperature was minus 25. There is no stopping Prairie queers.