In the last few years, the Canadian government has put on a theatrical production it calls “reconciliation” with Indigenous peoples. But that didn’t stop prime minister Trudeau from promising to ram the Trans Mountain pipeline through Indigenous lands, after the Federal Court of Appeal nullified licensing of the pipeline expansion in August. About half the Trans Mountain pipeline route passes through Secwepemcul’ecw – the unceded territory of the Secwepemc people. The traditional government of the territory does not consent to the pipeline.

It’s clearer than ever: “reconciliation” screeches to a halt as soon as it blocks the extraction of resources from Indigenous territories, or stands in the way of the accumulation of capital.

Many people believe that there is an unbridgeable rift between left labour activism and Indigenous struggles – and that means the settler working class and Indigenous people are necessarily at odds. It’s a conflict that burst into visibility in the ‘80s with a speech by American Indian Movement (AIM) co-founder Russell Means (though it’s been simmering since the genesis of settler-colonialism). It’s stirred up each time a union endorses a pipeline (like when the American Federation of Labour and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), the largest union federation in the United States, expressed support for the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016).

Theorists aren’t unanimous on the nature of this tension. Some, like Jodi Byrd, have argued that Marxism (which has been indispensable in describing class struggle) fails to account for Indigenous peoples’ demand for sovereignty and self-determination. There are also Indigenous Marxists, however, – like Archie Phinney, a Nez Perce anthropologist – who have described an affinity between anticolonial and class struggles.

In this issue of Briarpatch, Hans Rollman weaves together the stories of workers forced into the oil and gas industry, with narratives of Indigenous land defenders fighting the construction of the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project. Through interviews with Beatrice Hunter, an Inuk grandmother who participated in the 2016 occupation of the Muskrat Falls workers’ camp, Rollman lays out the physical, emotional, and mental toll of land defense.

“As feminist theories of emotional and psychological labour trickle into the mainstream, a parallel argument could be made for activism as a form of labour,” Rollman muses. But he’s rebuked by Denise Cole, an Inuk activist. Land defense is not work, she says – “This is my responsibility. It’s the protection responsibility I have for the land and waters and lives.”

“I think in settler-colonial political economies like Canada, which is still very much based off the extraction and exploitation of natural resources, indigenous land-based direct action is positioned in a very crucial and important place for radical social change.”

“We still have this understanding that the real transformative work and organizing in left politics emerges in the cities or among the working class,” notes Dené scholar Glen Coulthard, in an interview with Andrew Bard Epstein in Jacobin. “I think in settler-colonial political economies like Canada, which is still very much based off the extraction and exploitation of natural resources, indigenous land-based direct action is positioned in a very crucial and important place for radical social change.”

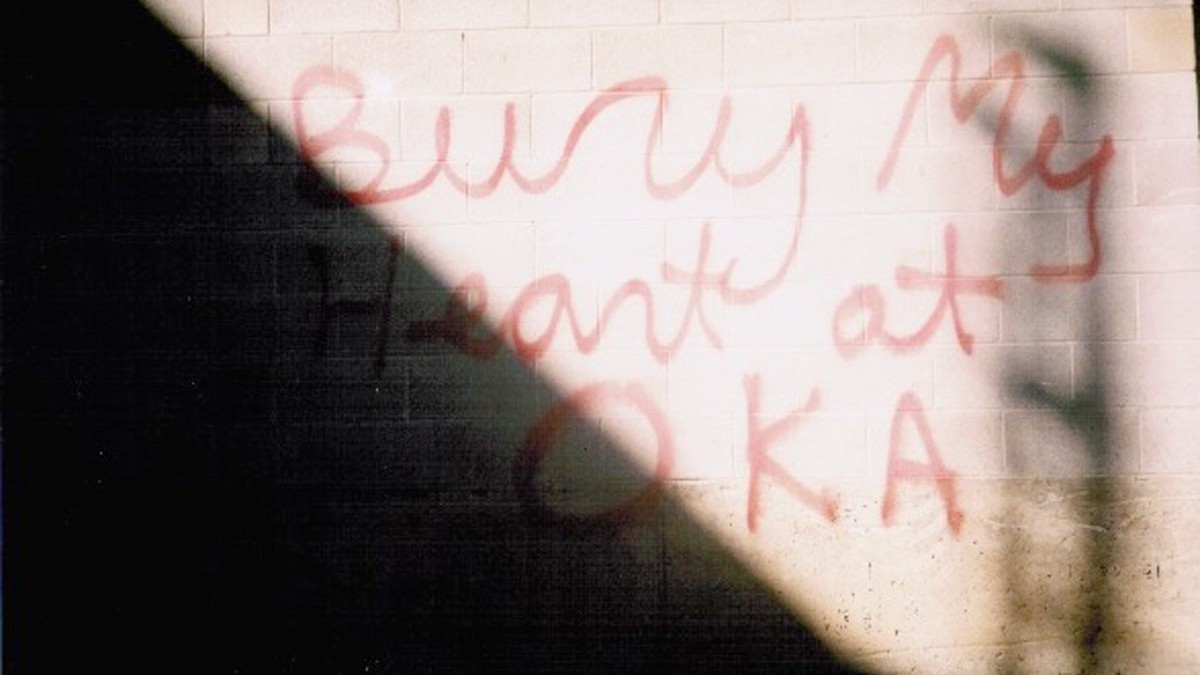

Indigenous land defense that blocks logging, fracking, drilling, mining, and hydro-electric projects on Indigenous land is resisting colonialism, but it’s also resisting capitalism. This was clear during the 1990 Oka confrontation, when armed Mohawk warriors from Kanesatake erected barricades to prevent the expansion of a private golf course on their land. It was clear, again, in October of this year, when Asubpeeschoseewagong Anishinabek (Grassy Narrows First Nation) banned all industrial logging in their territory and asserted that the First Nation will make its own land use decisions.

Most working-class settlers, like myself, struggle with how to survive the unending indignity of life under capitalism. We’re faced with the theft of our time for the profit of others. So, too, are Indigenous people struggling with how to survive colonialism, while the Canadian government and settler capitalists are hell-bent on stealing Indigenous lands and plundering or poisoning them for profit.

When we understand that settler-colonialism and capitalism are inextricable, we might begin to see that workers and Indigenous land defenders have more affinity in struggle than we previously thought.

There is not a clear or simple path forward, toward a working class – comprised of settlers as well as Indigenous folks – that is in solidarity with Indigenous struggles. Too many unions and settler labour activists have treated Indigenous people and land as nothing more than inevitable collateral damage of economic development. This is not reconciliation, and it’s certainly not decolonization.

But I wonder: what would the world of work look like if we, the settler working class, took up our responsibilities as grateful guests on Indigenous land? If we followed Indigenous peoples’ lead and pursued a relationship of reciprocity with the land and each other? If settler workers learned deeply about Indigenous struggles, working together against the joint exploitation of land and labour?