I’m on the cusp between two generations. Most categorizations place the end of generation X and the beginning of the millennial generation (sometimes called generation Y) at 1980 or 1982. I was born in 1981, so I have an appreciation for the music of both Beck and Beyoncé. Having a foot in both generational camps, and having baby boomer parents with whom I share a lot of values, gives me a unique perspective on the generation gaps we face today.

In much of the social and environmental justice work that I’ve been involved with in recent years, young people are frequently in the lead. The work often goes more smoothly, and is more enjoyable, when they’re around, though they do need to be encouraged and supported, as do most people when they are doing something for the first time.

Given my positive experiences, I am surprised by how frequently I encounter harsh and negative narratives about the millennial generation. Here, briefly, are the arguments:

- Millennials are entitled. They expect a trophy just for showing up, like they got at little league – if their parents could afford sports, that is. They don’t expect to have to work hard and they think jobs will be handed to them after college.

- Millennials are lazy. They prefer playing video games in their parents’ basements over getting jobs.

- Millennials do nothing to better their lot: they don’t vote or get involved in anything, probably because they are too busy on social media or catching Pokemon.

Such tension between generations has existed for centuries. But here’s the difference today: due to the state of the economy, largely orchestrated by the neoliberal turn of the 1980s and not by their own actions or values, millennials are widely reported to be the first generation that will be worse off than their parents.

Millennials grew up with governments that prioritized capital over the environment, marginalized socialist politics, and introduced free trade agreements that undermined the welfare state. Media vilified unions and politicians fought them. And now we’re seeing the results: precarious employment, heightened xenophobia and racism, a climate crisis met with government apathy.

But millennials are showing up for these issues.

Studies show that millennials are more likely to support climate action than older generations. And many millennials are building renewable energy co-operatives and working to phase out fossil fuels as well as helping change the conversation on these issues.

Young people are also rejecting racism and xenophobia in higher numbers than older generations. Both Brexit in the U.K. and Donald Trump in the U.S. have far less support among younger generations than older age groups, yet young people will have to live with the negative consequences for longer if Brexit proceeds and/or Trump is elected.

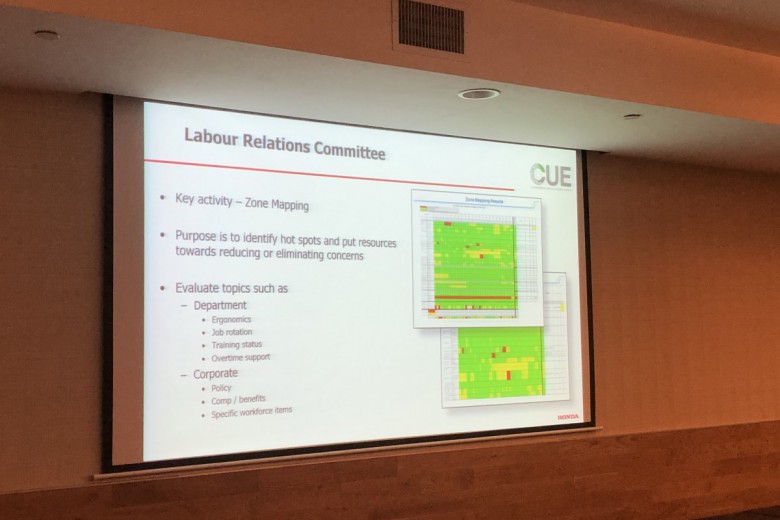

Perhaps where millennials are least successful is in helping to shape a labour movement that builds on their social and environmental justice values. The labour movement needs young people, and young people need the labour movement. I see some indication that the labour movement realizes this – the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour’s kids’ camp and youth committees within unions, as well as funding of programs like Next Up (disclosure: I coordinate Next Up Saskatchewan), are good examples. But I’m not sure that young people are similarly investing their energy in unions and workers’ struggles.

The fact that seniority rules in most workplaces are often harmful to young people – at least in the short term, and especially in a receding economy where jobs are being eliminated – doesn’t help the recruitment effort. For the connection between social movements to be made and strengthened, unions need to find new ways to engage with young people.

My fear is that the social safety net that many generations have worked hard to build will be lost and that no one will actually notice. Younger people won’t notice because most of the social programs from which they benefit existed before they were born, even if many of them have been eroded. But older people may not notice that things they’ve enjoyed and benefited from, such as full-time, unionized jobs, are being taken away from younger generations.

Rather than passively allowing ourselves and each other to think that young people are too irresponsible to save themselves, all generations need to find ways to learn from one another and work together to continue to make things better for generations to come. Just as our grandparents and great-grandparents did before us.