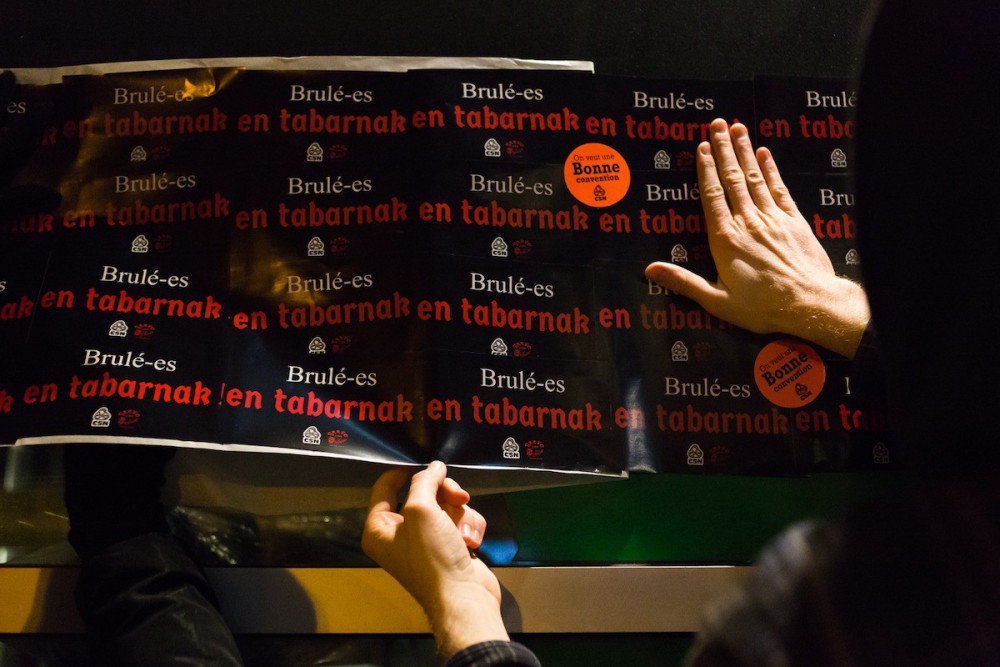

There’s a crowd of around 100 people on the sidewalk outside Cactus, a community organization in Montreal which contains the city’s first safe injection site. It’s December 18, 2019, and snow is falling. Dozens of placards above the crowd read “Brulé-es en Tabarnak,” French for “fucking burned out.” Led by members of the Union Thugs band, the crowd sings along to union songs. On the edge of the sidewalk, people light coloured smoke bombs to cheers from the crowd.

Inside Cactus, negotiations are going on between the organization’s administration and representatives of the Syndicat des Travailleurs et Travailleuses en Intervention Communautaire, which represents Cactus workers, for a new collective agreement. The STTIC is an umbrella union which represents workers at multiple community organizations in Montreal, and is affiliated with the Confederation des Syndicats Nationaux (CSN) federation. The word on the picket line was that the negotiators could hear the noise from outside, so picketers turned up the volume.

By the end of the afternoon, the two sides reached a tentative agreement. About a month later, Cactus workers adopted the agreement unanimously in a general assembly. The new contract contained substantial pay raises, the creation of a joint union-management hiring committee for new coordinators, improved health and safety standards, and improved maternity and sick leave protocols.

“Cactus now has the best salary in harm reduction,” says Emmanuel Cree, a member of the STTIC’s executive who works at REZO, another community organization affiliated with the union.

Cree is part of a team of workers that took over the STTIC’s executive board about a year ago and began a process of fundamentally altering its strategy. Like others on that team, Cree is a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, a radical, direct-action oriented union.

Yannick Gingras is a safe injection site worker at Cactus, IWW member, and president of the STTIC. “At Cactus,” he says, “if we were able to get better conditions in our contract, it’s because of the IWW model.“

Participative and combative

The IWW is unique among unions, in that it is deliberately unaccredited – in other words, it isn’t recognized as a legitimate labour union under the law.

Labour law in Canada gives unions exclusive bargaining power in workplaces where workers have voted to unionize. This gives unions leverage in negotiations – once workers vote to unionize, the union represents everyone, and has its dues automatically deducted from workers’ paychecks, guaranteeing institutional financing. Because the IWW is unaccredited, the union does not have recognition as the official bargaining unit, and instead signs up individual workers.

But labour law also comes with trade-offs and tactical limitations. Labour law allows workers to collectively bargain and strike, but only under very specific circumstances. When those circumstances aren’t in play, then workers’ official range of action is mostly limited to filing grievances against their employer. The IWW, in contrast, encourages workers to organize direct actions inside their workplaces. Its main tactical limits are based on how mobilized members are.

“A traditional union model can exist without anybody really being involved,” Gingras says. “You have a delegate that gives services to members, or you as a delegate bring demands to the employer, but without necessarily having the solidarity of your colleagues. The IWW model develops responsibility among members.”

“A traditional union model can exist without anybody really being involved. The IWW model develops responsibility among members.”

When they won the leadership of the STTIC, the team was engaging in an experiment. What might it look like if the IWW model operated inside a legal union?

“We’re trying to make the STTIC more like the IWW,” says Laurence Fortin, a Cactus worker and IWW member who is on the STTIC executive. “We want things to be more participative and combative.”

The team immediately got to work democratizing the union. “It used to be that the STTIC would only hold meetings open to everyone once a year,” Cree says. “We would basically just go over how the union spent money over the past year, and make some slight changes to the wording of bylaws – not the most interesting stuff.” The new STTIC held open meetings every two months, where members would decide on the direction the union would take.

Gingras has also been working to open up the CSN trainings to all members, rather than just elected delegates. “We insist that the training be open to everyone,” Gingras says, “so that everyone knows how to file a grievance, so that everyone knows their rights.”

“We’re not the same STTIC as before”

The negotiations at Cactus were a test case for how a more participatory and combative model might be applied to negotiations. The negotiations had already been going on for a year and a half before the team arrived, Cree says, without much progress. “It was the pretty typical trade union strategy,” he says. “There was a negotiating committee, a meeting every three months, and people would wear pins that say ‘On veut un bonne convention.’”

He says when the team won the leadership of the union, “Our negotiating strategy moved from being passive to more aggressive.”

Fortin was part of the mobilization committee at Cactus – tasked with organizing pickets and rallies, and doing outreach to other groups –, and says that at first, things were tough. In an early meeting, the only people present were herself and the CSN federation’s councillor. She started meeting her colleagues one-on-one, and eventually built up the mobilization committee to around a dozen people.

“I really had the fire under me,” Fortin says. “We didn’t have leverage, so the thing that attracted me to the [IWW] was the part that’s more combative.”

“We’re not just going to wear T-shirts anymore.”

“Our mobilization committee was open [to all members] from the beginning to the end of the negotiations,” Gingras says, “whereas we were advised to have a closed committee. It made it so that our actions were more diversified, and represented people more.”

At work, Fortin and others led a series of actions related to the contract negotiations. Workers would wear their union shirts during meetings with management, and would all stand up for the length of the meeting. As a group, they would enter managers’ offices to deliver letters containing the union’s demands. They gave out flyers to passersby outside the Cactus building. They took and withheld the sheets that management used to collect data, to create an incentive to negotiate faster.

They also “did something that had never been done to a community organization before, even though other unions do it all the time,” Cree says. In the middle of the night, a group of STTIC members covered the outside of Cactus with stickers emblazoned with their negotiating slogan, Brulé-es en Tabarnak.

“We showed the employers that we’re not the same STTIC as before,” Fortin says. “We’re not just going to wear T-shirts anymore.”

“We aren’t going to be cheap labour for the state”

“We call it the culture of the martyr,” Gingras says, describing a longstanding attitude among community sector workers. According to its logic, workers who demand better conditions are taking away scarce resources from service users.

“Our bosses are good at this, they love to play that card,” he says. "They know that we have close bonds with the users.”

For Cree, “the martyr complex also relies on the fact that the community sector is majority women. If it was majority men, there wouldn’t be that tendency, it wouldn’t be what we expect.”

Since the STTIC adopted a more participative and combative model, Cree says that he has seen these prevailing attitudes among community sector workers challenged. Now, he says, “for some employees, it’s become normal to be in constant confrontation with management, which wasn’t really the case previously.”

“Our bosses are good at this, they love to play that card. They know that we have close bonds with the users.”

“The community sector today also takes on a lot of the work that’s been left behind by the welfare state,” Cree says. “Today, it’s easier for us to say that we aren’t going to be cheap labour for the state.”

More STTIC-affiliated community sector workers are heading into negotiations, now that Cactus workers’ contract has been won. Dans La Rue, a multi-service organization which serves homeless people, has already begun negotiations. REZO, where Cree works, is starting negotiations in the next few months.

For Gingras, this organizing is not just about him, but also about the people he interacts with every day. “If we improve the quality of life for workers, we’re improving the quality of services.”