I have been on remand at Pine Grove Correctional Centre in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, for 17 months. Being on remand means being locked up while waiting for your trial or conviction, simply for offences you were alleged to have committed.

One woman, a former roommate of mine at Pine Grove, was denied bail and sat on remand for nine months. After she finally went to trial, she had to wait a month for her verdict. Prior to her verdict being read, her lawyer and the Crown were conversing on her sentence, and her lawyer told her that the Crown was asking for a sentence of three years. Because of this, she assumed she was going to be found guilty. The next day – on May 31, 2021 – she was found not guilty on all counts and released. So, before the judge had even read the verdict, the Crown was already preparing to sentence her based on allegations alone.

Another woman, who lives on the same unit as I do, told me that her legal aid lawyer made her plead guilty to all her alleged offences in hopes of a reduced sentence. She didn’t know she could plead guilty to some charges and plead not guilty to other charges. So now she is going for an expungement hearing, hoping to remove the unjust convictions from her record.

In 10 out of 13 Canadian provinces and territories, there are more prisoners on remand than there are sentenced prisoners.

According to section 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, we have the right to be “presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal.” But the way I have been treated in the justice system makes it clear that anyone in prison is presumed guilty until proven innocent. I’ve been put in a cell for 24 hours a day for a week, if not more. No change of clothes, no shower, no hygiene kit, one blanket, no hair elastic, no phone to call home, and no nutritious meals. It’s a vicious cycle – when you can’t look presentable in front of a judge, you’re more likely to end up back in jail.

In 10 out of 13 Canadian provinces and territories, there are more prisoners on remand than there are sentenced prisoners. This is especially true in the Prairie provinces – in Alberta, 71 per cent of prisoners are on remand, in Manitoba it’s 68 per cent, and in Saskatchewan it’s 51 per cent.

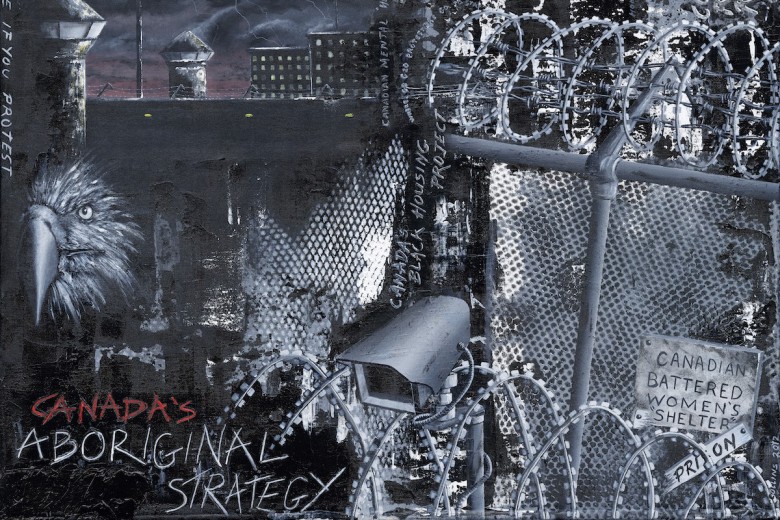

Indigenous people are targeted for imprisonment at much higher rates than non-Indigenous people in Canada, especially in the Prairie provinces. In 2014/2015, Indigenous adults made up one quarter of all the admissions to remand across Canada, despite only being 4.9 per cent of Canada’s total population – in Manitoba and Saskatchewan in particular, over 70 per cent of remand admissions were Indigenous people. In 2018/2019, of the 309,664 court decisions made, 11,258 cases were acquitted, meaning the accused were found not guilty of the charges.

It’s a vicious cycle – when you can’t look presentable in front of a judge, you’re more likely to end up back in jail.

People who are on remand for short or long periods of time lose everything: our children, our jobs, our funding for college. In other words, we lose the three things that are the most important to ensure that people do not reoffend: family, employment, and education.

If the government wants to bring down the crime rate, they’ve got to consider doing what the Dutch are doing. Dutch judges are much less likely to give a jail sentence and when they do, the sentences are short – three-quarters of all sentences are less than three months. Instead of jail time, judges tend to assign a financial penalty or community service. In the Netherlands, they shut down most of their prisons because their crime rate is so low. If judges and lawmakers acted this way in Canada, I believe there would be many fewer people in Canadian prisons.

Know your rights

While incarcerated in 2019, I was being represented by a lawyer paid for by legal aid. I called him to set a date for us to go through my disclosure, which is the evidence that the police and Crown were planning on using against me in court. He didn’t come when he said he was going to. I called him the following week and voiced my concerns regarding my disclosure. He then said “You know who pays for you to eat and sleep in there? You know who pays me to represent you? I do! Us taxpayers. So you don’t call the shots!” I hung up on him, then called and wrote a letter to legal aid about the situation. They said there was nothing they could do. I tried firing him but he just didn’t want to let my case go. At trial I fired him in front of the judge and told the court I had lost confidence in him. I’d lost confidence in the legal aid system alltogether. I now pay a different lawyer out of my own pocket.

It’s important to educate people about the law and their rights, so things like these don’t happen to them, their friends, or their families. Information that applies to inmates can be found in the Correctional Services Act 2012, Correctional Services Regulations 2013, and the book Human Rights in Action: Handbook for Provincially Sentenced Prisoners in Saskatchewan.

People who are on remand for short or long periods of time lose everything: our children, our jobs, our funding for college. In other words, we lose the three things that are the most important to ensure that people do not reoffend: family, employment, and education.

Indigenous Peoples’ rights are recognized In the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which states, “Indigenous peoples have the right to the full enjoyment, as a collective or as individuals, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms as recognized in the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law.” The government also has to consider that as Aboriginal Peoples, we have rights as stated in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the treaties signed between our leaders and the Crown, and Section 35 of the Constitution.

But many Aboriginal people cannot access these rights while in prison, for many reasons. When being admitted to the correctional facility, admission staff don’t ask questions that are vital to incarceration, like “Can you read? Can you write? What’s your first language?” These are questions that are important for us Aboriginal people, especially when prison involves so much paperwork and so many calls with lawyers. In Pine Grove, I have come into contact with a few women who can’t speak English – Cree is their first language. Luckily for them, I am fluent in Cree and English, so I was able to advocate for them and get them in touch with translators for their court hearings.

I strongly suggest that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) hire more bilingual staff who speak English as well as Indigenous languages like Cree and Dene. I believe this will help prisoners to better understand their rights and help with their intake and rehabilitation. CSC also needs better orientation programs to help prisoners understand rules and regulations.

Take direct action

But sometimes educating prisoners about their rights isn’t enough. When the justice system breaks its own rules, we need to find other ways to demand fair treatment.

Over the past year, medical staff were not replying to our request slips. We started putting in complaint forms – but those were not being addressed in a timely manner, either. The nurse went as far as to deny us our medication, saying that medication isn’t a right, it’s a privilege. Serious medical issues were not being taken seriously. We have little remand programming – the programs that do exist can be finished within a couple of weeks. The majority of programs, especially ones that are vital to rehabilitation – from the children’s visit program to addictions counselling – are only available for sentenced offenders.

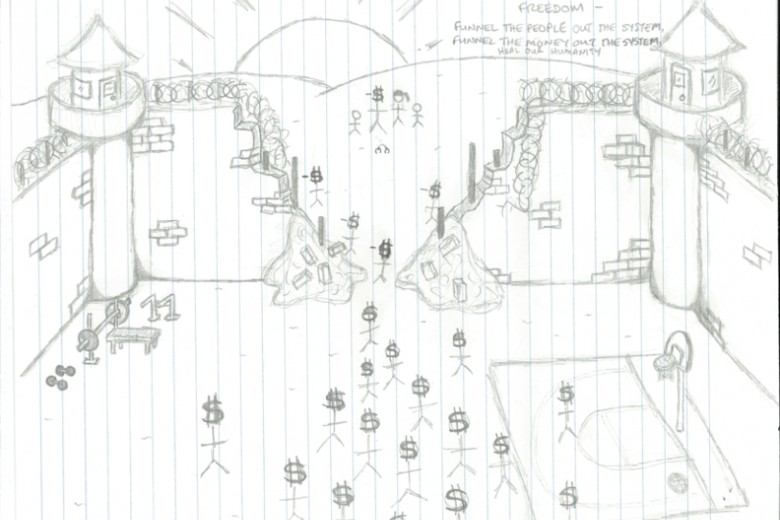

A group of women and I got together and wrote down the things that were lacking. I said these issues would be a good reason to go on strike – we would demand a change to these conditions and hope our voices would be heard by the public.

At that point, I made a promise to myself that I would keep hunger striking until Cory arrived in Prince Albert on April 13.

On April 1, 2021, I started a hunger strike. At one point it was only me on the hunger strike. Then five women in Unit 3 joined, and some other women joined from Unit 4. The first five days the staff called it a “refusal.” Then, a woman was hospitalized for low potassium levels. It took five days for them to take us seriously. Nurses finally started checking in on us daily. More people began to join the strike during my second week, because more staff actually wanted to listen to our demands.

When I started the hunger strike I got in contact with Beyond Prison Walls Canada, an anonymous activist who advocates for incarcerated people and their families. They started a movement. Cory Cardinal, a prisoner justice advocate who was recently imprisoned in the nearby Saskatoon Correctional Centre, said he was going to come protest in front of Pine Grove in solidarity. At that point, I made a promise to myself that I would keep hunger striking until Cory arrived in Prince Albert on April 13. So I was on a hunger strike for 13 days. Nurses came to assess our vitals, sugar levels, and weight every day. They gave me Gatorade on the seventh day to help with electrolyte imbalances. I lost close to 10 pounds in those two weeks, and my blood sugar was low. On the fifteenth day, when I started eating again, I had to slowly introduce myself to food again so I wouldn’t get sick.

I did this for the women who are afraid to voice their concerns.