“Education costs money, but then so does ignorance.” — Sir Claus Moser

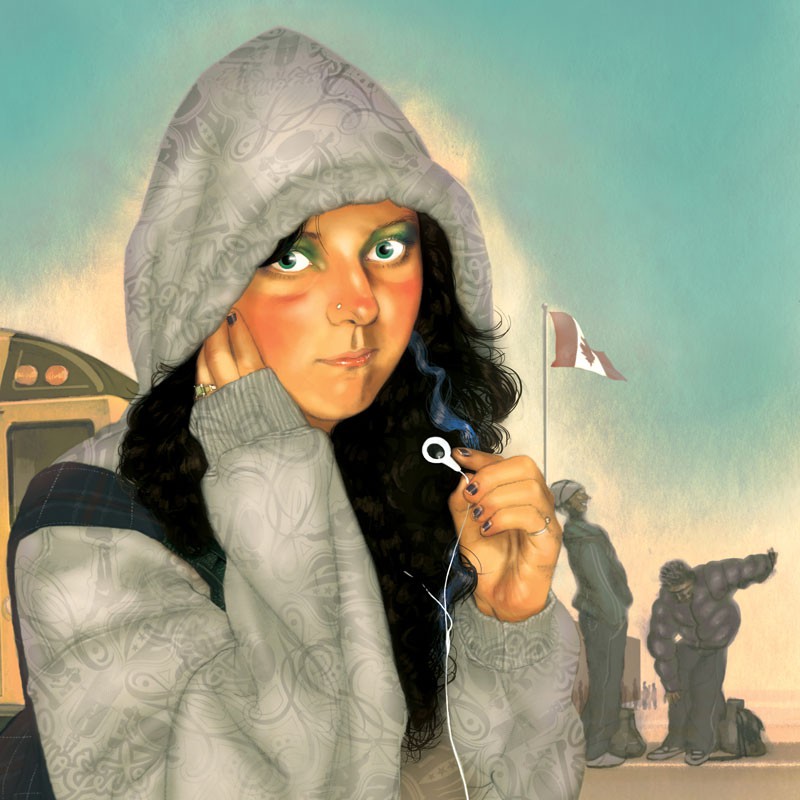

In 1992, I was a high school graduate enrolled in studies at the University of Saskatchewan. Post-secondary education had never been a can-do for me – it was always a must-do. My family was entrenched in middle-class mediocrity, my dad a high school teacher and my mother a stay-at-home mom. The only means of financing an education was through government-funded student loans, but according to the loan assessor that year, my father, the sole breadwinner of the family, earned too much (at $45,000 per year) for me to qualify for assistance. He managed to fund that initial year; the next six years of study – four university, two college – were my responsibility. If I wanted the education I felt I needed to secure some kind of reasonable career and livelihood, I, like so many other students, would have to take on thousands of dollars in debt.

Education is increasingly thought to be for the good of the individual rather than for the greater good of society – a belief that has made it politically acceptable to place the bulk of education costs squarely on the shoulders of the students seeking that education. The cost of a year’s tuition for a full-time Canadian undergraduate arts student has skyrocketed in recent years, from $1,800, to $2,400 in 1995, to $4,700 in 2008 – an increase of 260 per cent over the past 16 years. The result is increasing social stratification, as students from lower-and middle-class backgrounds, who can’t pay up front, either take on long-term debt, if they qualify, or simply don’t pursue further education.

The total Canada Student Loans debt surpassed $13 billion in January of this year, and continues rising at a rate of $1.2 million per day. These numbers don’t include provincial student loans, bank loans, or credit card charges. The average cost of attending university, including tuition and living expenses, is now more than $12,000 per year. According to Statistics Canada, the average student debt for a Bachelor’s degree is just shy of $25,000, and $15,000 for college. One in four student-loan-carrying graduates has reported difficulty in repaying their loans, with about 30 per cent defaulting on payments.

The consequences of such debt burdens on graduates’ lives are significant, limiting their choices in all kinds of ways. Student loan obligations, according to Katherine Giroux-Bougard, National Chairperson of the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), reduce a new graduate’s ability to “start a family, invest in other assets, buy a house, do career-building volunteer work, or take lower-paying jobs in their field to get a foot in the door.” Other consequences of high student loan debt, Giroux-Bougard says, are “that some people will choose to not attend post-secondary education at all or will choose to not attend some programs.”

When professional programs were deregulated in Ontario in 1998, explains Giroux Bougard, many people from rural areas and low-income families were shut out. Statistics Canada reports that between 1995/1996 and 2001/2002, tuition fees rose by 168 per cent in dentistry, 132 per cent in medicine and 61 per cent in law, compared to a 34 per cent overall increase for all undergraduate programs in Canada. Many capable students from lower and middle-income families are unable to consider such professions because they simply can’t afford the tuition.

The Canada Student Grants Program, introduced in last year’s federal budget, which was put forward in response to the outcry for more post-secondary financial support, is a victory for the CFS’s “Grants NOT Loans” campaign. The Program provides needs-based bursaries throughout a student’s years of studies (in monthly amounts of $250 for low-income students and $100 for middle-income students) to offset rising student debts.

Giroux-Bougard believes this is a good start. “The Federation has been calling for this for years. Canada is one of two countries in the world that does not have a program of grants. It is a first and important step for the government to take.” Giroux-Bougard is now calling on the government to add more money to those grants and to the Canada Social Transfer payments to the provinces, thus reducing the share of post-secondary costs borne directly by students. Government operating grants made up 80 per cent of university operating revenues in 1990. By 2007, that had fallen to 57 per cent.

I turned 35 in June and am only now nearing the retirement of my massive student debt of $73,000, of which roughly $21,000 is accumulated interest. According to the latest National Graduates Survey (2007), 56 per cent of graduates financed a post-secondary education by taking out loans.

Are post-secondary institutions merely selling high-priced degrees, diplomas and certificates to those who can afford them, or are these institutions serving a greater good by advancing knowledge and promoting creative and critical thinking? By placing the burden of paying for higher education on the student, our society is saying there is little social good or intrinsic value in an educated citizenry; it is the individual who benefits, not society as a whole. Therefore, the student pays.

Treating education like a luxury good impoverishes everyone. A society that recognizes the social value of an educated population should also recognize the public obligation to fund it. As Giroux-Bougard says, “Saddling a generation of students with billions in debt will have far-reaching implications for Canada’s economy and socio-economic inequality.”