In the months since the election that secured Stephen Harper’s Conservative majority, many people on the left have repeated the refrain, “Don’t mourn; organize.” While it is an apt and important directive, what does it really mean? How will we organize? In the absence of clear strategies for social change, we risk working ourselves into the ground without making the gains we need.

The right in Canada has clearly understood the importance of developing a strategy with winnable goals, and in the last 10 years it has succeeded in shifting public discourse far to the right of where it had been for decades. Stephen Harper went from an outspoken conservative activist who had served only one previous term as an MP to consolidating the Canadian right into a single political party and controlling, unfettered, the federal government.

By contrast, the radical left has largely been in decline over the past 10 years, both in visibility and influence. Indeed, many radicals feel we do not have a fighting chance, and carry on with a bizarre mantra akin to “everything is hopeless, but we have to do something.” Often we talk about a radically transformed society in much the same way as Christians talk about heaven or the Rapture – something to look forward to far, far in the future, but not something that can be attained, even in part, in a span of months or years.

To reverse this downward spiral, we must develop winning strategies of our own. If we hope to achieve a more just society in the future, we need to alter the way we work in the present. We must develop strategic action plans that increase the organized power of our movement and result in concrete and measurable improvements in people’s lives.

I would like to offer four thoughts as my contribution to this ongoing discussion within radical community and worker organizations in Canada.

1. A lost cause?

On November 16, 2010, a small community-based organization representing migrant farm workers signed a historic agreement with their employers to improve conditions for workers in Florida’s tomato industry. This marked the conclusion of the most recent chapter in a story that began in 1993, when the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) was formed to demand improved working conditions for migrant farm workers and an end to poverty wages. The 2010 agreement between the CIW and the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange, the organization representing landowners, extended the CIW’s “fair food principles” to over 90 per cent of the Florida tomato industry. These principles include a strict code of conduct, a co-operative complaint resolution system, a participatory health and safety program and a worker-to-worker education process. The agreement also solidified a victory previously won by the CIW from tomato purchasers to increase farm worker wages by almost 100 per cent.

It is hard to imagine a group of workers more marginalized than those who form the membership of the CIW – largely undocumented migrants from Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean – or an adversary as relatively powerful as the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange, which brings in billions of dollars in profit every year. To many, the CIW’s cause, while just, seemed lost from the beginning. Indeed, from our current vantage point, it is easy to view a campaign such as this one as a lost cause.

Our causes are not lost. But in the absence of a coherent strategy, our activism is unlikely to produce any clear-cut victories. Whether we are planning a short-term campaign or the theoretical work of long-term, widespread and systemic social change, the process of strategy development is the same. To begin developing a winning strategy, we must first ask ourselves: what does victory look like?

In a context where victories on the left are rare, the campaign led by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers – which was won through commitment to a well-planned strategy – has much to teach us. The CIW had a clear vision of justice: increased wages and improved working conditions. Based on this foundation, they developed concrete goals that would help them realize their vision. Their fair food principles were clear and well-defined, and enabled workers to determine, without ambiguity, whether they had been successful in their campaign or not.

Our strategies – as a movement, as a coalition, or within our respective organizations or communities – must begin with a clear vision developed through democratic discussion. This vision can then be refined into tangible goals to work toward. For example, a vision of “housing as a right” may lead to goals such as a national housing strategy, with guaranteed annual funding for rental housing and new housing co-ops owned and controlled by their members, and legislation that would give homeless people the right to seek a court order forcing the government to provide them with housing.

As we develop these goals, we need to be both creative and disciplined, allowing ourselves to dream big, while at the same time stopping ourselves from degenerating into arguments over the details of our vision of a post-revolutionary society. After setting our goals, we can begin to build a strategy that will lead us to victory, a strategy that must be constantly evaluated as it unfolds and adjusted as necessary.

2. Power, to the people

On June 25, 2011, Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party legislated an end to the Canadian Union of Postal Workers’ strike. The newly invigorated NDP, recently elected as the official Opposition, attempted a filibuster, prolonging debate over 58 hours. In the end, however, the legislation passed and the strike was ended. A number of prominent radicals later used the NDP’s failure to stop the legislation as proof that there is no power in voting. In fact, the Canada Post situation suggests otherwise. Harper was able to force workers back on the job, on terms favourable to the employer, because his party secured enough seats to constitute a majority. He has tremendous power to shape the conditions of our lives, power he gained through the electoral process, however illegitimate we believe it to be.

Power is the ability to shape our lives and the world that surrounds us. We build our power by organizing collectively. Unions, for example, have great potential power, as they have a defined membership, organizational structure and mandate. Whatever form our organizing takes, our strategy for social change must have at its core a plan to build the organized power of oppressed people.

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers understood power well and developed their strategy accordingly. After identifying their goal, the CIW identified the target of their campaign: the growers. Targets are the people who have the institutional power to concede to your demands. They are those who can sign the cheque, cancel the contract, introduce or repeal the legislation and so on. If, during your strategy development, you arrive at a long list of targets, your goal is likely not adequately refined. In our hierarchical society, the kind of power needed to make institutional change is almost always vested in a single person or a small number of people.

In the small town of Immokalee, Florida, the majority of workers toil on fields owned by a small number of companies. Because the CIW wanted to improve wages and conditions for all of their members – who often worked on several farms in a given season – they organized a campaign targeting all growers. They engaged in three community-wide work stoppages and a high-profile hunger strike but, after years of working to get the growers to concede to their demands, realized they did not have the power necessary to force their targets to capitulate.

The CIW then identified a secondary target that had power over the growers – the corporations that purchased their produce. In 2001 the CIW launched a boycott of Taco Bell. They called on their allies to stop buying food at Taco Bell restaurants until the fast-food giant took responsibility for human rights violations in their supply chain. They also demanded that Taco Bell support their campaign to “pass on a penny per pound” pay increase for farm workers and to buy tomatoes only from compliant Florida growers.

In 2005, after a hard-fought and high-profile campaign, Taco Bell agreed to meet all of the workers’ demands, and the CIW called off the boycott. Taco Bell could not present the agreement as a goodwill gesture as it was clearly a concession to the power of the workers who had struggled for it. The CIW then moved to target McDonald’s, another of the growers’ biggest customers.

The right takes the project of building institutional power very seriously. As Tom Flanagan, Conservative academic and Harper confidante, has said, “… controlling the government as often as possible is the most effective way of shifting the public philosophy.” The radical left has shown that mass movements, outside of government, can also be powerful enough to shift public philosophy and to radically improve people’s lives. Our movements must become a growing source of organized power that can be consciously wielded and directed against our targets in the service of attaining our goals, and affecting a lasting shift in the balance of power.

3. Seeing through clear and open eyes

While the G8 and G20 countries met in southern Ontario in June of 2010, thousands of people marched and rallied in a week of protest. These actions were met with massive police repression, and by the end of the week hundreds of people had been assaulted and harassed, and over 1,000 people had been arrested. The targeting of activists and militants continued for weeks, and several hundred faced charges by summer’s end.

A month after the G20 protests, the coordinating body for much of the radical left during the protests released a statement insisting that in “June 2010, on the streets of Toronto, the people won.”

This assessment was based primarily on the fact that participants of diverse struggles and community organizations were leading many of the street protests, and did so despite overwhelming police intimidation. If our only goal was to voice our discontent, in all its diversity, then the mobilization against the G20 was a victory. However, if the goal was to change the destructive policies of the G20, to alter the balance of power between the economic-political elite and the rest of us, and to inspire those not already committed to join us, our success was neither clear nor resounding.

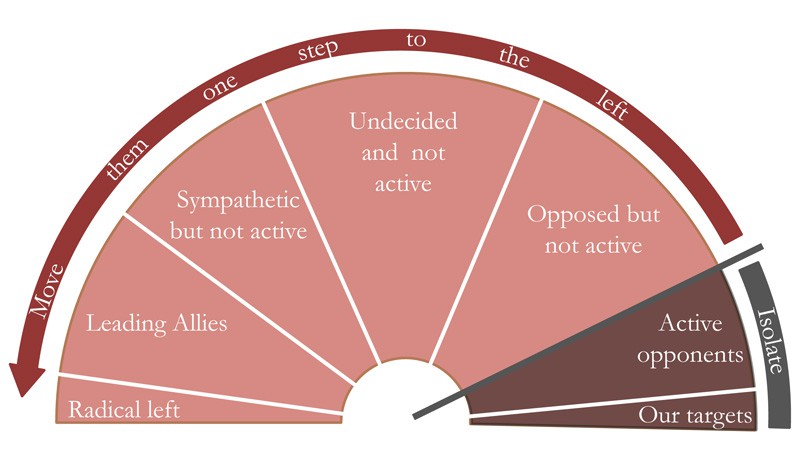

Our success in these struggles will depend on our ability to see the world through clear and open eyes, and to make reasoned assessments of our strategies, actions and their outcomes. This process demands that we identify the people and groups that constitute our base, our allies and our opponents.

Our base (or constituency) includes those oppressed people and communities that are already active or organized. Many members of unions and community organizations are within our base, and can move their organizations to become part of our base or movement. Our potential base includes all people oppressed by capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism and ableism, but who are not actively resisting that oppression.

Our allies are those who share some, but not necessarily all, of our goals, with whom we can work on a common cause. Many unions are our allies. Their primary goal is not the end of capitalist oppression, but rather the improvement of their members’ working conditions and wages, and some positive social reforms. Single-issue social justice organizations are another.

Our opponents are organizations and groups that benefit from the oppression we are fighting against. They may control the levers of power directly, or have influence over our targets without having that power themselves. Landlord and industry lobby groups, the Conservative Party, the Fraser Institute, organized racist movements and Zionist lobby groups are some examples of opponents.

The state is our primary target, because it can give us much of what we want. The state, however, is a complex institution. Its overarching purpose is to protect the interests of capital and maintain the status quo, but it is also composed of individuals and institutions with shifting or competing allegiances. If we view the state only as a monolithic oppressive entity with a single, unified purpose, we miss opportunities to exploit those differences to win concessions.

In their struggle for fair food, the benefits of the CIW’s lucid self-assessment were clear. When they determined that their well-organized base lacked the power necessary to force their target to concede, they identified a network of powerful allies. They reached out to students because Taco Bell targeted them as consumers. They also allied themselves with religious groups that they hoped would be motivated by a sense of justice and moral outrage, and which were already organized into congregations and church networks.

To develop a strategy capable of radical social transformation, we must also assess the power of our movement relative to that of our opponents and targets. We should have a clear sense of the numbers of each group and their geographical distribution, the donations and resources at their disposal and so on. The number of active and engaged people in radical movements in Canada number only a few thousand at most, and much of this activity is focused in a handful of urban centres and Indigenous communities across the country. Certainly there are more people who are sympathetic to some of our goals, or who would benefit from the changes we seek, but they are only potential constituents until they become active in some way.

By contrast, the Conservative Party has organizers in each federal riding who fundraise, coordinate get-out-the-vote work during elections, monitor local media and engage in other campaign work. To support their work, the Conservatives received donations from 95,010 people, totalling over $17.4 million in 2010. This may seem like an impossible sum for radicals in this country, but it amounts to a relatively small donation of $183 per person, or a monthly donation of only $15. If the left could do more to secure commitments like this from our base, whether they are in the form of time or money to build our infrastructure or pay organizers, we could dramatically increase our power.

By explicitly identifying our base, our potential constituents, our opponents, and those somewhere in the middle, and by assessing each group’s strengths and weaknesses, we can make informed choices about our direction as a movement and the tactics we choose to target our opponents where they are weakest.

4. Throwing punches

The CIW came to their recent victory after a long struggle. They employed a variety of powerful tactics targeting their employers during the first seven years, including three work stoppages, a month-long hunger strike and a 370-kilometre march across Florida. When they changed the focus of their strategy to target fast-food chains and corporate buyers of Florida tomatoes in order to pressure the growers into conceding, they employed many of the same tactics.

Students and other social justice groups held demonstrations in cities across the United States, and helped the CIW mobilize cross-country caravans and several national days of action. Some student groups were successful in forcing franchises off their campuses. Religious leaders motivated their congregations to join the campaign, collected donations for the CIW, and held press conferences to exert pressure through moral persuasion or embarrassment, to isolate the fast-food giants from support, and to polarize the debate around the issue. By the end of 2008, the CIW had won campaigns against the four largest fast-food companies in the world.

Our strategies must employ a variety, or diversity, of tactics to achieve our goals. These tactics must be directed at our targets to pressure those with the power to give us what we want – whether that is a change in immigration law, more affordable housing, or a complete shift in government policy. It is not the perceived militancy of our tactics that matters, but whether they effectively pressure our target to concede to our demands and, while doing so, help build our base. The pressure must not be rhetorical, but actually felt by the target.

The Ontario Coalition Against Poverty – a radical anti-poverty organization based in Toronto – organizes under the slogan “Fight to win.” They understand that those in power do not listen to moral argument, but that the poor will have to build a movement capable of forcing politicians to act.

We should take this lesson to heart, but when we repeat this slogan, we should not make the mistake – as many have done and continue to do – of putting the emphasis on “fight” rather than on “to win.” How we fight should be determined by how it helps us win. Throwing one’s fists into the air in all directions – hoping that you land a knockout punch – is not how one wins a boxing match. Not every target is vulnerable in the same way. A disruptive direct action may be effective against one but not another, and what works once may not work a second time. Many of our targets are immune to protests and demonstrations, but this does not mean they cannot be successfully pressured.

Our actions must be well-planned manifestations of our power, directed with clear purpose against our targets. We must be able to win short-term victories as steps in our strategy and to strengthen our movements so that, eventually, we will have permanently altered the balance of power and become a force to be reckoned with – a cause not lost, but rather an organized movement capable of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)