Former farmers driven north in search of work have found that the rules governing the free flow of capital don’t apply to them—indeed, that crossing borders has never been more difficult.

In a village called Anagua, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, a young man named Antonio sits at an old school desk and recounts his experience as a migrant worker. Like many thousands of others each year, he paid a coyote, a people smuggler, between $1,500 and $2,000 to take him across the border and into the United States. The journey meant walking for two days and two nights through the desert. He feels lucky to have made it across alive.

Once Antonio arrived in the United States, he had a difficult time finding work. After a long search, he eventually found a job in construction but struggled with life as an undocumented worker. Once he had paid off his debt to the coyote he returned to Mexico, managing to bring a little extra money home with him. He hopes he won’t have to go again.

An older farmer sitting close to Antonio concedes that most people from their community who have gone to the U.S. do make more money than if they were to stay home. “But,” he says, “they aren’t happy.” It is clear throughout my journey along the U.S./Mexico borderlands and through rural Mexico that this is a common sentiment. Almost everyone I meet along the way is doing their best to make it in Mexico so they won’t have to become migrant workers in the U.S. or Canada. It is generally understood that life as a migrant is not easy; most would prefer to stay home.

No matter where they are, for whom they work, or what kind of work they do, migrant workers live in a perpetual state of precarity. Unable to claim the legal protections provided to citizens, frequently forced to leave families and communities behind for long stretches of time, required to be transient to follow temporary and seasonal work, and isolated from the surrounding communities, these economic migrants increasingly enrich their host countries with their labour, even as their home communities sink further into poverty and social disintegration.

There are, of course, degrees of precarity within the migrant workforce: those with legal status may claim some acknowledgment of their existence and some protections under the host country’s laws, while those without status are often subjected to the most egregious exploitation. On the other hand, migrant workers with status are subject to a more calculated form of exploitation on the part of host governments. This regulated and exploited migrant workforce has become a key pillar of wealth generation in both Canada and the United States in recent years, as the neoliberal mantra of freedom for capital, goods, and investments has decimated the rural Mexican economy. Former farmers driven north in search of work have found that the rules governing the free flow of capital don’t apply to them—-indeed, that crossing borders has never been more difficult.

Work, justice and dignity is the slogan of Maya Pan, a women’s co-operative in El Paso that works with women who have been left unemployed by NAFTA and the loss of factories to Mexico or elsewhere. Working from a place of hope, these women are organizing to ensure that they have safe places to live and to educate themselves for jobs in a post-NAFTA El Paso.

Alien Nation

On a recent visit to the border city of El Paso, Texas, I met with Carlos Marentes, the director of the Border Agricultural Workers Project and Sin Fronteras Organizing Project, both founded in the early 1980s. Both projects are housed in a migrant worker centre where workers, mostly men, come to rest, eat and receive help in accessing services such as health care. There is an obvious overlap between the two projects, including staff, space and membership, yet the focus of each project is quite different.

As Carlos explains, “We see that our work includes two very important elements. One element is symbolized in Sin Fronteras, which deals with the day-to-day problems farmworkers face. The other ingredient is the organizing and educational work, which is the Border Agricultural Workers Project. The intent is to push for the organization of farmworkers so that they plan long-range solutions to their problems—-making changes to the agricultural system.”

The border separating Texas and New Mexico from the Mexican state of Chihuahua is a stark and discouraging place. The city is divided literally by the border—-El Paso on the American side and Ciudad Juarez on the Mexican. In Juarez, American and internationally owned factories have become the dominant employers since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) nearly 14 years ago. Hundreds of people living in Juarez also cross the U.S. border each day to work in the nearby fields, and thousands more live on the El Paso side, many without adequate housing. Some of these workers have documents allowing them to work legally in the U.S.; some don’t.

In recent years, and particularly since the massive immigration reform protests of spring 2006, the American public has begun to pay a lot more attention to its southern borderlands. It is becoming more and more difficult for Mexican workers to cross into the U.S., both legally and illegally, due to increased screening and militarization of the border. Once they have crossed, life is still difficult. Workers are regularly harassed for documentation and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s constant presence is impossible to ignore.

In the wake of President Bush’s failed immigration bill, it is unclear whether a new immigration policy will materialize in the U.S. What is clear, though, is that the current debate will not lead to a radical shift in the way the U.S. views its border territories. According to Carlos Marentes, immigration reform proposals to Congress, whether proposed by Democrats or Republicans, reliably contain two major themes. The first is that any discussion of immigration is invariably framed in terms of “national security” and “strengthening the national border.” The second is the implicit recognition that the U.S. economy depends on cheap labour, traditionally supplied by large numbers of undocumented workers. With the recent crackdown on so-called “illegal aliens,” however, other sources of cheap labour must be found or manufactured—-hence the widespread calls for temporary work programs.

“It appears to be a contradiction,” says Marentes, referring to the fact that capital and goods can cross borders with increasing ease while people face ever greater restrictions. But it’s not. “We want cheap labour but we want labour we can control. We cannot control undocumented workers, but we can control somebody with a contract—-basically tie that person to certain companies, certain employers.”

Calls for a widespread amnesty that would allow undocumented workers to gain status and therefore be legitimately permitted to work in the U.S. have been vehemently opposed by many Republicans and a number of right-wing groups. Marentes believes that the powerful corporate lobby in the U.S. simply does not want a workforce that has freedom of movement. In fact, many industries, including large-scale agriculture, have long relied on temporary or undocumented workers who can be paid at or below minimum wage, are willing to work extremely long hours doing difficult, monotonous work, and who have very few options for finding other employment. This need to control an exploitable workforce signals a deep distrust and dislike of “outsiders” in the American psyche, even while the historical dependence of the U.S. on such a workforce is widely recognized.

Looking through the fence from New Mexico into Chihuahua. During recent protests, activists who suppport a more open border between the U.S. and Mexico cut a hole in the fence and sent people through to the Mexican side. The fence will soon be replaced by a permanent wall if many U.S. politicians get their way.

Et tu, Canada?

Many Canadians view the immigration debate to their south as a uniquely American problem. But Marentes says the Canadian approach to migrant labour is the model the U.S. is increasingly copying: an economy fueled by temporary, officially imported workers with limited freedom—-in other words, legally sanctioned precarity.

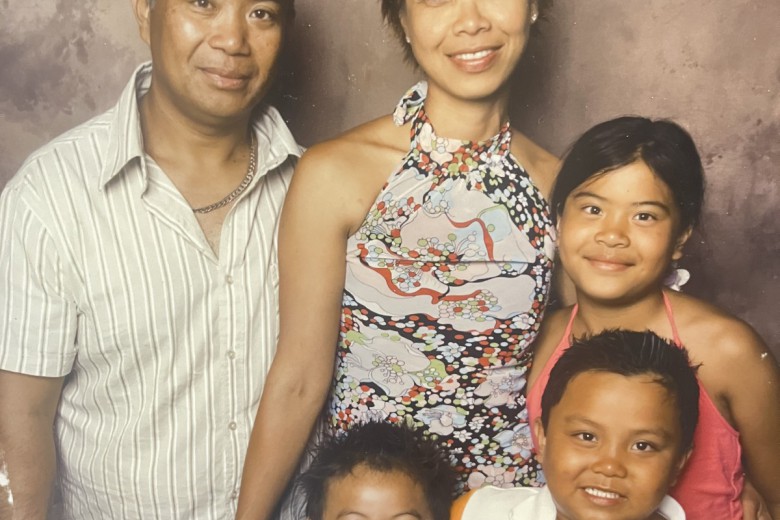

Canada, of course, has a fraction of the undocumented workers of the United States, due in large part to our distance from countries of origin and our inaccessibility via land. Instead, we have thousands of documented migrant workers working in a wide variety of jobs across the country each year. Over 20,000 migrant farmworkers from Mexico and the Caribbean come to Canada every year through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program alone. Thousands more come from as far away as the Philippines and China to work as nannies, in construction, and in the service industry through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and the Live-in Caregiver Program. In total, nearly 100,000 temporary work permits were issued in 2005 alone. Many of these workers are isolated and Canadians are generally unaware of their existence or the extent of the wealth generated from their labour.

How, in a society that subscribes to the notion that every person has certain inalienable rights and freedoms, has our economic system become so dependent on an unfree workforce that is systematically denied citizenship rights? Canada’s agricultural sector is a good place to look for answers. In this sector, our increasingly export-oriented food and agricultural policies go hand-in-hand with a heavy—-and mounting—-reliance on migrant labour. In 1988 Canadian agri-food exports were $10.9 billion. Nineteen years later, in 2007, our agri-food exports are worth $32.65 billion. Farms in Canada have gotten larger, more technologically sophisticated and more focused on escalating production for export markets.

This transition has had at least two major impacts on rural communities. First, as farms get larger and fewer in number, rural communities have suffered an exodus of people to Canada’s urban areas (our own scene of migration). For many small, family farms, the declining rural population has made it increasingly difficult to find seasonal labourers from within the community. Farmers are also struggling with net farm incomes below zero, despite being among the most conventionally efficient agricultural producers in the world—-a situation that increases the pressure to hire labour as cheaply as possible.

Second, many highly industrialized farms are no longer family-owned enterprises. In their 2006 study entitled “Migrant Workers in Canada: A review of the Canadian Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program,” the North-South Institute found that “farm sizes have increased due to expansion and consolidation of farms, leading to a reduction in family farms and their replacement by corporate farms needing wage labour.” This industrial model of farming requires migrant labour as a way to keep the cost of labour low while still being able to produce mass quantities of food for a global market. Agriculture in the Global North thus increasingly relies on migrant labour from the Global South. The model has begun to spread to other sectors, including construction, hospitality, and domestic labour.

Carlos Marentes, Director of the Border Agricultural Workers Project and Sin Fronteras Organizing Project in El Paso, Texas, believes that the powerful corporate lobby in the U.S. simply does not want a workforce that has freedom of movement.

Fleeing from NAFTA

In Mexico, the causes of migration are numerous, but there are common overarching themes. The same free trade deals that have successfully created huge export markets for Canadian produce and furthered the industrialization of our food system have effectively decimated the Mexican countryside.

Victor Quintana, a leader with the farm organization Frente Democratico Campesino in Chihuahua, blames both NAFTA and the structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund in the 1980s for the current economic crisis in rural Mexico. He tells me that 80 per cent of people living in extreme poverty in Mexico are in the countryside, and that the crisis came in two waves. Structural adjustment programs came first: state investment in the countryside was reduced; agricultural loan programs were dismantled; minimum payments for crops were stopped; extension and research were dramatically cut back. Then the free trade agreements arrived, which further exacerbated the situation by rapidly opening the Mexican economy to a flood of foreign goods that in turn undermined the value of Mexican production and resulted in the collapse of commodity prices.

One of the direct consequences of NAFTA on rural Mexico has been massive migration, and according to Quintana, this outcome was anticipated even before NAFTA was signed: “One study estimated that NAFTA would displace about 1.4 million rural Mexicans, and that 600,000 displaced farmers would migrate (illegally) to the United States over five or six years.” More recent estimates by Mexican farm organizations suggest that approximately four million people were affected: two million left their land and another two million lost their jobs.

“The social fabric has been torn apart because all the young men migrate,” says Quintana. “Many of the women migrate now too. A lot of villages in the region can’t organize a baseball team because there are not enough young people to play.”

There are many organizations in Mexico working to address the economic and social crisis in the countryside. Some of them are working at a very local and practical level, such as the El Ranchero Solidario co-operative in Antonio’s community of Anagua, Chihuahua. El Ranchero Solidario is a farmers—- co-operative formed to pool the members’ production, which has now expanded into running a thriving local grocery store as well. Other organizations are focused at the political level. UNORCA, a national peasant organization, has been part of the continuing struggle to convince the Mexican government to renegotiate NAFTA and remove agriculture from the agreement entirely. These farm organizations recognize the need to change national and international agricultural policies in order to stem the flow of northward migration.

Our food system, as framed by NAFTA and other international trade agreements, has a core need for a temporary and highly controlled workforce to produce cheap goods for the international market. The irony is that these cheap goods flood into local markets in countries like Mexico and cause the displacement of millions of peasants and farmers. Completing the vicious cycle, these peasants often join the migrant labour force that produces the cheap goods from the North that are flooding their local markets and driving southern farmers out of business.

This situation is not inevitable, however. Organizations like Sin Fronteras and El Ranchero Solidario have envisioned and are working toward an alternative system where local communities regain control of the food system by embracing the principles of food sovereignty“šÃ„îthe right of communities and nations to organize food production and consumption according to local needs. The hope is simple and powerful: that peasants and farmers can continue to grow their own food and that workers on both sides of the border will have fair wages, good working conditions and dignity of life.

With the support of the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation’s Global Youth Fellowship, Martha Jane Robbins traveled through the U.S. and Mexico in July and August of 2007 to meet with peasant leaders and rural communities struggling with migration issues.