Brown, Black & Fierce is a collective of Indigenous people, Black folks, and people of colour (IBPOC) who are dedicated to centring the experiences and voices of queer, trans, gender non-conforming, and two-spirited people. Located in Amiskwaciwâskahikan (Edmonton), Brown, Black & Fierce works to dismantle white supremacy through activism, art, peer support, and organizing work.

On November 7, 2015, the collective held the inaugural Brown, Black & Fierce Festival organized by and for IBPOC. The festival unpacked issues of immigration and decolonization, and processes of racialization. Briarpatch spoke to collective members, Alex Felicitas, Ruby Diaz Smith, Leila Sidi, Jenni Roberts, and Aurélie Lesueur, to learn more about their work. See more of their work.

Ruby Diaz Smith has described racialized and queer people as existing in a state of being “small enough, palatable enough, and quiet enough for our own survival.” What is BB&F, and how does it challenge the forces of silencing and oppression inherent in white supremacy?

BBF: The collective began with two of the members, who barely knew each other at the time, reaching out to say, “I’ve heard you speak of a desire and a need, a craving for space like this. What if we organized something small together?” We never thought it would become anything bigger than a small evening of IBPOC [Indigenous, Black, Person of Colour] performances and conversations. As we put our heads together, though, it became clear how necessary this event [the Brown, Black, and Fierce Festival] was, both in our personal lives and for our diasporic communities – including for those displaced on their own lands, on which we are settlers. Half of our collective had never done organizing like this before, and almost all of us had only ever organized in circles of mostly white people. Taking our own space changed everything. We found we no longer had to keep quiet in meetings; we no longer had to silence our own needs, discomforts, and experiences of violence and oppression from our colleagues. The strength of this realization within our small group extended to how we began to shape all of our interactions with power holders in the community. When applying for funding, we didn’t parse words or try to aim for a neoliberal “middle,” but stood firm in who we were, why we were, and what we were trying to accomplish. It is so much harder to be “fierce” and “unapologetic” as an individual, but working with each other was so validating and real to us.

Monetary considerations have also been a way in which we challenge oppressive systems and white supremacy. We are fully committed to compensating people for their work. For the festival, for example, all facilitators, performers, and other organizers were paid an honorarium. We sourced materials for the workshops. We offered subsidies for those travelling in for the festival, and we held a free meal, prepared by Jenni’s mom, for about 100 people. Too often, women and IBPOC folks are not compensated for their time and work, so this has been an integral part of our goals – to be able to guarantee an honorarium for each person involved. Well, except for ourselves, but we’re working on that! I think it’s super-important to note that we’re almost entirely self-funded through community support.

At the beginning, we said, “You know what? There’s no way we are going to qualify for any funding applications that the city or other organizations might have. It’s time we look to our peers, white folks who have much greater access to wealth and resources, to help us out on this one.” It was actually pretty incredible to see so many white folks stepping up consistently and also quietly to provide so much necessary support. From organizing and managing multiple fundraisers, to donating their skills and artwork to silent auctions, or using their positions of power to provide us with free spaces to hold our events, people stepped up to increase the capacity and well-being of us as POC organizers, which was something most of us had never experienced before. We’re not handing out cookies here, but we think it’s important for white people who want to act as allies to know that there are very concrete and tangible ways to support IBPOC people.

What does “fierce” mean?

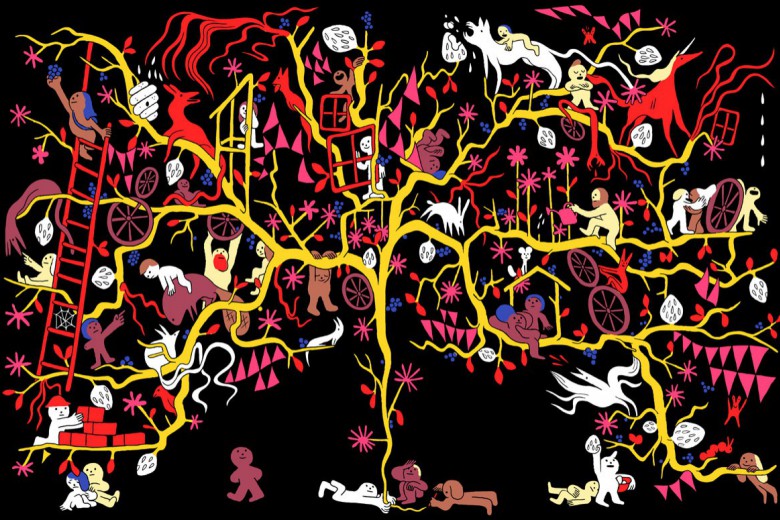

BBF: Fierce means so much: it’s something that everyone defines for themselves, and that definition is always flexible, multi-toned, and varied. Our collective members are fierce as individuals in ways we define for ourselves, but we are also fierce as a group in how we make decisions and how we structure our organizing to be independent of white supremacist organizations that gate-keep and hold power over us. Fierce means resistance; for us, it has meant making a deliberate choice around funding, and reaching out to our community first instead of trying to jump through hoops in Edmonton’s art scene. It has also been about fiercely supporting, loving and listening to each other throughout an intense experience of organizing. We are fierce in our breakdowns, in our vulnerability, in our need for care. We are fierce in saying “NO” to those who try to tokenize us within their “multicultural and therefore not racist” agendas. We set out to be welcoming and celebratory of all aspects of people’s fierceness, no matter how hard or soft.

How many people are in BB&F, and how does the collective grow?

BBF: At the moment there are five of us who have done the core organizing, but many others have been ever-present along the way, from IBPOC supporters to white allies. Our work is not “ours” – we simply felt the call and had the energy to step up and act on a need that has long been felt in our communities. After the festival, we had many people approach us to say they wanted to help organize future events; lots of people have also connected hoping to have us partner in some way with their endeavours and groups. The collective will expand, shrink, and become many things as we continue. It’s clear by the amount of things we’ve committed to in the next six months that we’re not planning on stopping anytime soon, but we also hold that we don’t wish to act as gatekeepers to POC organizing and events. We don’t wish to enact lateral violence by taking over other IBPOC spaces or endeavours, or monopolizing all of the available resources. That’s an important piece for us right now – looking to groups who have long been doing this work but who don’t hold the same access to social capital that we do. We’re all in our mid-20s to mid-30s and have pretty good access to mainstream resources (language, education, technology, and so on). We’re hoping that whichever way the collective grows, it will be organic, not forced, and will remain a nurturing experience for those involved.

You recently put on the Brown, Black, and Fierce Festival. What did you want to achieve through it, and what were some of the powerful lessons from it?

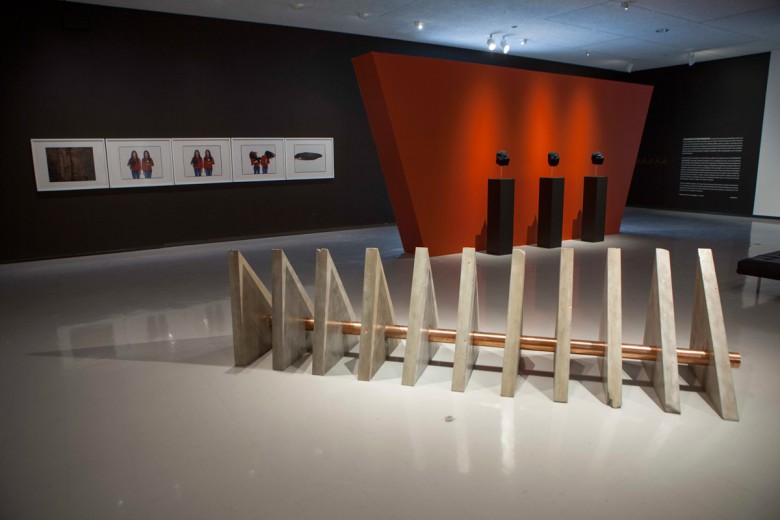

BBF: First and foremost, we wanted a space for IBPOC people who were creators in some way to be able to express themselves freely, independent of the agendas of well-meaning but white-centred organizations and events. We wanted a space that would be safe for those expressions, conversations, and connections to be made. Initially, we gave ourselves about three months to put together a small evening program. Based on responses to our first steps, though, we quickly realized that this would grow into something beyond our initial plan. First and foremost, we wanted it to be a genuine experience for all involved. There were many difficult periods along the way, and certainly the festival itself revealed new and nuanced issues that were huge lessons for us. Namely, we found that there is much work to be done to ensure that those who are light-skinned, white-passing, or even half white are able to find safety and community. There has been so much internalized oppression and a push toward being model minorities that often we perpetuate colonial and lateral violence on our peers. Ultimately, it became a day-long festival with 17 workshops and just as many performances. Jenni’s mom cooked for 100 people, and the following day, two POC healers offered their skills and attention to those in our communities.

Who do you consider to be the audience of the collective’s work and activism?

BBF: We consider the audience to be Indigenous folks, Black folks, and people of colour of all ages, especially those who identify as women, trans, queer, two-spirited, and gender non-conforming. The festival saw many folks from those communities attend workshops and perform; however, it was quickly evident how much more work we need to do to reach out to Métis Indigenous folks, white-passing folks, and racialized newcomers to these territories. For us, this piece is crucial, because without the active participation and direction of these communities, we are re-enacting settler colonialism. When we hear that Métis folks feel they need “markers” to feel accepted in spaces, or that they need to constantly “prove” themselves by having to explain their histories and land base, it means that there is still much more work to be done. White settler colonialism has impacted all of us, and I think it’s important to have real discussions about the ways in which that has shaped our identities and experiences. Those are parts of us that can be painful to remember or be reminded of, or to have brought up to us in an accusing or excluding manner by other settler POC folks. Many folks who are light-skinned, half white, or white-passing chose to not participate in the festival due to discomfort around their lightness, or felt that the collective or other participants wouldn’t accept them. They are whom we still want to reach the most at this time.

How does your location in an urban space, Amiskwaciwâskahikan (Edmonton), affect your work, fierceness, momentum, and motivation?

BBF: Amiskwaciwâskahikan is a place where many Indigenous folks and racialized folks experience more outward racism than a lot of places north of the 49th parallel. Confederate flags are a common sight, and let’s not forget that the Aryan Guard and the KKK continue to recruit and organize in this city and nearby. This is also a place to which many of our parents have come from other countries to seek safety and more opportunities. And, foundationally, this is the place where Indigenous folks for thousands of years have made their homes and lives.

These histories are not mutually exclusive. But for Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities, it has meant outward attempts of erasure of our languages, our cultures, and displacement from our homelands. We’ve had to develop thick skins, do a lot of things we haven’t wanted to do in order to survive, and have been forced to stay silent. I think we are coming to a time now where things are changing, and we are starting to recognize that this is the moment to rise up. We are ready to talk about truths, and not have to sugarcoat them for others. We are coming to a time now where too many of us have gone missing, or have taken our lives, and we are saying now: “not one more.” We are coming to a time where we are no longer apologizing for our existence, and we are asserting our presence and our future.