When I began medically transitioning in my mid-20s, I didn’t think much about reproduction or how my decisions would impact my options for having a family. Freezing my sperm felt like a waste of money, and I’d always known that I didn’t want to have biological children, worried they might inherit my predisposition for depression – though I now realize that thought carries more than a hint of internalized eugenics. Shame runs deep when you’re a transgender woman of colour living in a world that piles vitriol on your doorstep every day.

These days, when I sit down to figure out how I can start a family of my own, I think less about the individual decisions I’ve been able – or required – to make and more about the societal structures and political climate in which I’ve made them. I think of the trans women and transfeminine and Two-Spirit people I know and love: a community that is largely scattered, isolated, disenfranchised, and fearful, especially when it comes to our capacity to have families. I think of the few queer parents I know, how grateful I am to be an “auntie” in their chosen families, and how much I long to be a mother in my own right.

The argument that motherhood belongs to only a subset of women is not new. This same argument has long worked to not only “other” trans women from cis women, but also to separate racialized women from white women, and poor women from wealthy women.

One potential option that has been discussed widely is uterus transplants, which have already been carried out successfully on cisgender women. Last February, an obstetrician-gynecologist at McGill University made the case that trans women should be considered for research trials on the procedure, that they should have “equivalent rights to fulfill the reproductive potential of their gender.” Anti-trans groups have aggressively voiced opposition to the idea, including the Women’s Human Rights Campaign, which issued a statement that “[m]aternal rights and services are based on women’s unique, sex-based capacity to gestate and give birth to children. These rights and services, and the word ‘mother’ itself should stay reserved for persons of the female sex.”

An earlier draft of this article confronted those organizations’ rhetoric head-on, challenging the logic of their positions that are actually, as writer cosima bee concordia pointed out succinctly on Twitter, “doing the most anti-feminist thing possible by defining cis women’s purpose as having babies.” In many ways, it is difficult to reason with these groups’ logic. It saps my energy, and my passion, to exist and create in a world that is so obsessed with either putting women like me on a pedestal so high and unstable that we must inevitably fall from it or eradicating us from existence, from history, from thought. Instead, I would like to advocate for a world that doesn’t frame trans motherhood as either a medical breakthrough or a forbidden evil, but rather as a radical act of love and care, a step toward building a society that honours and supports all families and parents, especially those who have historically been barred from existing.

Uterus transplants sound like a really cool idea. They would also likely be incredibly expensive and inaccessible for many – perhaps most – trans women and transfeminine people. We already know who would be excluded: fat trans folks, for one, are still often barred by their doctors from receiving gender-affirming surgeries. Surgical interventions are important, and they can be life-saving for those who undergo them. But they are a solution for certain individuals – not the deep excavation of the roots of transmisogyny, racism, and poverty that would be necessary to improve the world in which all trans women live.

If we could reimagine our world in order to prioritize trans women’s well-being – especially that of Black and Indigenous trans and Two-Spirit mothers, who experience some of the worst of what the system has to offer – maybe we could make the system more equitable and safe for all parents and children.

It’s important to note that trans women aren’t the only people who are barred from being mothers, or whose motherhood is put in jeopardy. As recently as 2019, Indigenous women have faced forced sterilization; Black mothers in the U.S. and U.K. are four times as likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth as white mothers; and Black and Indigenous children are apprehended from their communities at disproportionately high rates by the broken foster care system. There have always been – and continue to be – strong forces working to stop oppressed people from becoming mothers.

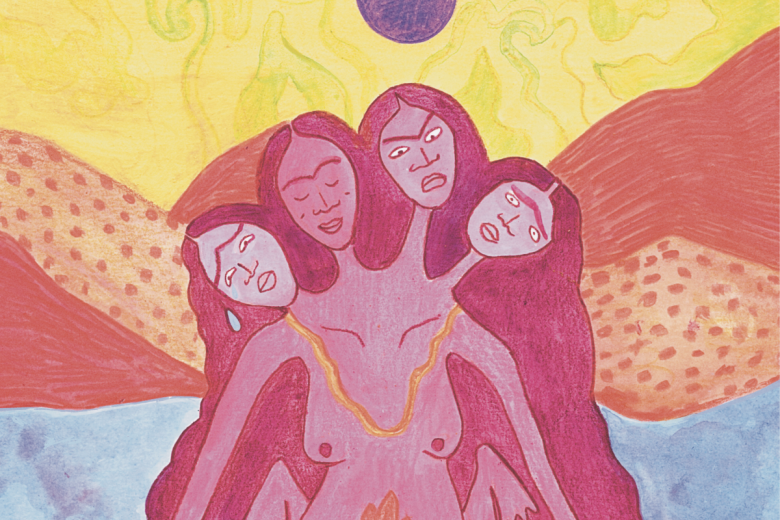

The argument that motherhood belongs to only a subset of women is not new. This same argument has long worked to not only “other” trans women from cis women, but also to separate racialized women from white women, and poor women from wealthy women. When I imagine a world that creates space for all oppressed community members to build families, to craft collective legacies of love and care, I imagine both white and BIPOC cisgender women allying themselves with trans women, transfeminine people, and Two-Spirit folks – seeing each other as sisters, as kin, as family. If we could reimagine our world in order to prioritize trans women’s well-being – especially that of Black and Indigenous trans and Two-Spirit mothers, who experience some of the worst of what the system has to offer – maybe we could make the system more equitable and safe for all parents and children.

Maybe we could make a world in which all women, all people could be parents, in defiance of those who say we should not be able to have families of our own.