For Hua Hsun Tseng – Watson, to his friends – 2015 had been the worst year of his life.

He had survived open-heart surgery, and had lived in fear of rupturing the artificial artery that had been installed in his chest. Then, six months after the surgery, once his doctor had finally allowed him to begin driving again, a truck rear-ended his car while he was on a family trip to Kamloops. Watson and his family survived unscathed, but the car was totalled.

“The car accident changed my religion,” Watson tells me over coffee at a Tim Hortons in Richmond, B.C.

“After the open-chest surgery, I was very, very nervous every day. I was thinking about whether the [prosthetic artery] was broken, or if I was going to die. I had nightmares every day. But after the car accident, I feel that God was telling me, if he wanted me to die, I could die anyway.”

“So I wanted to do something good for my friends,” he says. Watson was looking for a mission. He found it at the River Rock Casino Resort, where he had been working as a cook for two years.

Watson had heard about a union drive that had started with the dealers. He knew that there were issues – many workers had seen no increase in wages in 12 years, and his wage as a chef de cuisine stood at $13 an hour – but he wanted to talk to somebody before jumping in. After waiting for a front-of-house staff member to come down to the kitchen to sign up the cooks on union cards – “nobody came,” he says – Watson decided to call the B.C. Government and Service Employees’ Union (BCGEU). He would soon sign up most of his department, 79 cooks in all.

When Watson made that phone call, he was stepping into a fight with one of the biggest players in Canada’s gaming industry.

When Watson made that phone call, he was stepping into a fight with one of the biggest players in Canada’s gaming industry. The Great Canadian Gaming Corporation, the owner of River Rock, operates 22 gaming facilities across Canada and Washington State. River Rock remains B.C.’s highest grossing casino.

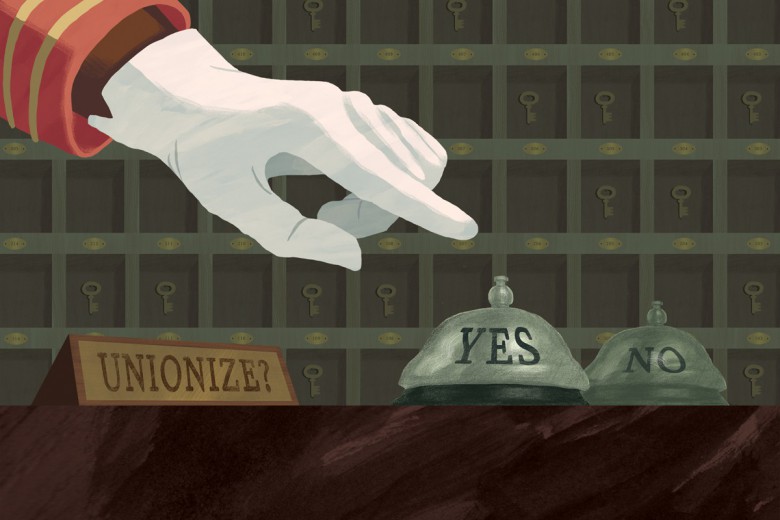

That casino would go on to be unionized by the end of the year. The successful drive represented B.C.’s biggest private-sector labour certification in more than nine years. In all, 977 workers, including dealers, slot attendants, cashiers, cooks, chip counters, and hotel room attendants joined BCGEU, making River Rock the union’s biggest workplace in the gaming sector. Over half of BCGEU’s members are provincial government employees, while the rest are divided in a number of different sectors, ranging from college support staff and credit union tellers to social service workers, First Nations government staff, and hospitality workers.

Within six months, in May 2016, another Great Canadian casino, the Hard Rock Casino Vancouver, located a 40-minute drive away in the suburb of Coquitlam, also voted in favour of union certification. Like River Rock, the Hard Rock had been the focus of several unsuccessful union drives in the past. This time workers voted overwhelmingly in favour of the union. In all, 430 workers from the Hard Rock joined BCGEU.

The rapid unionization drive of these two casinos represents a transformational change in B.C.’s gaming industry. According to a media release issued by Great Canadian prior to these certifications, only 600 of the company’s total 4,863 employees were unionized. The unionization of these two B.C. properties represented a tripling of the company’s unionized workforce.

Backslide in Canadian labour organizing

The overall trend of unions in B.C., as with the rest of North America, has been a long decline in membership. Between 1981 and 2012, the unionization rate of B.C.’s labour force shrank from 43 per cent to 30 per cent, according to Statistics Canada. For workers in the private sector, the numbers are even lower, with only 18 per cent of employees represented by a collective agreement.

According to David Camfield, an associate professor of labour studies and sociology at the University of Manitoba and author of Canadian Labour in Crisis, few Canadian unions have attempted to stop this backslide by putting significant resources into non-union organizing. Unions in the United States have begun to act more decisively, owing perhaps to lower density and a smaller public sector.

“That sense of crisis is not widely felt in the officialdom in Canada. There is still an enormous amount of inertia,” he explains.

Camfield believes that labour unions in Canada desperately need to figure out how to run successful organizing in the private sector, where the majority of job growth has occurred. The hospitality and restaurant sector makes strategic sense as a target area because it is difficult to outsource work in these industries.

“It’s labour-intensive work and it has not been subjected to automation,” he says.

In this context, the organizing wins at River Rock and Hard Rock were significant in terms of both their rarity and their origin. These large organizing drives began on the shop floor, in a process initiated by workers themselves rather than by union staff. BCGEU organizing staff would later step in, playing a crucial role in coordinating the union certification effort. But much of the social cohesion among workers was already there – as was the agitation.

“Everything was getting worse year by year”

The majority of B.C. casinos are still non-union. According to Stephanie Smith, president of BCGEU, only 14 out of 42 casinos in B.C. are unionized. Ten of those casinos are members of BCGEU.

According to several workers I spoke to at River Rock, the seeds for the successful union drive were sown several years prior to 2015. A change in management in the late 2000s prompted a freeze in wages across the board. In addition, management began pressuring long-term, high-seniority staff to take a buyout.

One man, who had worked for over 10 years at River Rock and spoke on condition of anonymity due to the then-ongoing negotiations, said that some high-seniority staff were asked to quit with no buyout package.

“The remaining staffed looked at it like, ‘that’s not right!’ I mean, people contributed 20 years’, 30 years’ experience to the company and then all of a sudden they say you don’t need them, get rid of them,” he said.

Other cuts were apparent. Watson noticed that staff meals went from buffets to micromanaged portions, wages remained stagnant, and management failed to fix potentially dangerous hazards. Watson describes a gas leak in a grill that remained unfixed for months. Veteran staff avoided using it, but when new cooks mistakenly tried turning it on, it would often produce dangerously high flames.

“Everything was getting worse year by year,” he says.

A similar dynamic had taken hold at Hard Rock. In 2013 Great Canadian had rebranded Coquitlam’s Boulevard Casino, spending $15 million in the hopes that it would draw a younger clientele.

“Staff are going to be able to high-five the guests,” said Great Canadian’s then-vice-president of communications, Howard Blank, at the time.

Revenues increased significantly at the casino, and the expanded music venue hosted performances by aging rock icons like Ringo Starr and Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash.

But like River Rock, Hard Rock’s management soon began cutting back on staff. John Erickson, who at the time had been working for seven years as a security guard, tells me that after the rebranding, the company went after high-seniority employees.

Revenues increased at the casino, and the expanded music venue hosted performances from aging rock icons like Ringo Starr and guns n’ roses guitarist slash.

But Hard Rock’s management soon began cutting back on staff.

“There were a lot of employees there that were long-term, they were essentially pushed out the door to get newer employees in that didn’t have as much vacation time,” says Erickson.

According to Stefan Avlijas, a member engagement specialist with BCGEU, Great Canadian has continued much of this behaviour in the midst of bargaining.

“The employer really does treat them, quite frankly, as replaceable,” Avlijas told me last February.

Great Canadian declined to comment for this article, but its 2016 year-end financial results indicated that River Rock has experienced a $19 million decline in revenue. The company’s 2015 year-end financial results also indicated a decline in River Rock’s revenue. Despite this backslide in profits, River Rock continues to be the top-grossing casino in the province. Most of the company’s other properties, including the Hard Rock, experienced significant increases in revenue in 2015 and 2016. The company generated $566 million in total revenue in 2016, a 22 per cent increase from 2015.

“Nothing can go wrong because we are the worst”

There was no single spark that launched the River Rock union drive of 2015, according to workers and union staff. The tension had simply been simmering for almost seven years.

“When I convinced people to sign a union card, I always told them nothing can go wrong because we are the worst,” Watson tells me with a chuckle.

The union drive began after dealers decided to take a lead in signing up their co-workers. Table games represented the biggest department by far in the casino. Most of the workers in this department are Chinese, along with a high number of Taiwanese immigrants. Watson, who is also Taiwanese, suggested that the concentration of these workers made him confident that he would face little backlash because of his outward support for the union.

“If you fire me, the Taiwanese will not be happy,” he tells me with a shrug.

Many supervisors were also Chinese, which Watson suggested contributed to sympathy for the union drive among middle managers. Chinese-Canadians make up the majority of the population of Richmond, the Vancouver suburb in which River Rock is located.

According to Smith, the workers who contacted BCGEU were unusually enthusiastic compared to her experience in other union drives.

“We literally had organizers set up in local coffee shops,” Smith says in a phone interview, “and there were workers lined up out the door.”

More often than not, BCGEU’s past successful union certifications have come about because of employer-sanctioned card check agreements, which do not involve a union election, according to Smith. The bottom-up nature of River Rock’s drive was unusual.

“Once we organized, it took them a few days to get to 90 percent, to get ratified. It showed that a lot of people were pissed off at their employer,” one long-time worker tells me.

Although the card signing proceeded rapidly, the certification votes, which were split by department, took several weeks. Workers voted overwhelmingly in favour of the union.

This successful vote provoked keen interest from workers at Hard Rock.

“With Hard Rock, River Rock had gone first,” says Erickson. “If they had not unionized first, I don’t think that a lot of our staff would have had the courage to vote.”

In a union drive, fear is often a countervailing force to talk of change. Some workers, when faced with a union card, fear adverse effects on their job security, health benefits, or relationship with their immediate supervisor. Employers often wage anti-union campaigns that either suggest or bluntly claim that unionization will bring about negative consequences. Union staff members are often limited in their ability to counter employer claims since they are usually not permitted to speak to workers at the workplace.

Curiously, in the cases of both Hard Rock and River Rock, the employer campaign appears to have been remarkably unsophisticated.

Curiously, in the cases of both the Hard Rock and River Rock, the employer campaign appears to have been remarkably unsophisticated. The employer’s communication with staff consisted largely of a series of memos posted on employee tack boards discouraging votes for the union. Management made little attempt to single out or intimidate workplace leaders. One worker told me that many floor-level supervisors were sympathetic to the union drive.

Dragging out the first contract

Although Great Canadian does not appear to have pursued a vigorous campaign to keep its workers from unionizing, the company has employed a strategy of dragging out bargaining for the union’s first contract. Workers at River Rock have been bargaining for over a year; Hard Rock, almost as long. According to union staff, the strategy of BCGEU has been to secure a contract with River Rock first, before focusing on achieving a similar agreement for Hard Rock. Great Canadian, for its part, has employed Borden Ladner Gervais LLP, one of the largest law firms in Canada, as its bargaining representative.

At both casinos, the top bargaining issues are workplace safety, job security, scheduling and, most importantly, wages. At River Rock a wage freeze has been in place for 12 years.

“Relative to other workers in the sector, these people have been paid far less, despite the irony that it’s the highest grossing casino in the province,” says BCGEU treasurer Paul Finch.

Last December, while the bargaining process was ongoing, BCGEU secured a significant victory. Great Canadian abruptly announced that it would be changing its policy regarding vacation payouts. The company had previously banked unused vacation pay at the end of each year. Pressure from the union appears to have forced the company to pay employees arrears due for previous years in which they had not used their entire vacation. For some workers, this back pay was as high as $5,500.

“It’s equivalent to wage theft,” Smith tells me over the phone.

Although there have been some attempts to put pressure on River Rock management through workplace action, workers and BCGEU organizers were largely met with company intransigence. In April, in a demonstration of workplace strength, over 200 workers crammed into a conference room where bargaining was taking place. Great Canadian representatives refused to show up.

On June 9, workers had planned to wear stickers on their uniforms that simply said “$7.34 Million,” indicating the average two-week earnings of River Rock Casino. Early that morning, though, management representatives had walked into the staff break room and told workers and union staff that anyone wearing a sticker on the floor would be sent home for the day. Later the same day, Great Canadian legal representatives did not show up for previously scheduled talks with BCGEU bargaining committee.

In early August, workers filed into a banquet room at the nearby Radisson Hotel Vancouver Airport to take a strike vote. Of the 860 workers who voted, 99 per cent supported strike action.

One month later, on September 25, Great Canadian management and BCGEU reached an agreement, which allowed for significant wage increases and improvements in health benefits, paid leave, and vacation entitlements. A media release from BCGEU says that wages will rise over the course of the four-year agreement by an average of 19 per cent.

But Great Canadian may have been prodded to settle as a result of other factors. As negotiations moved to mediation in September, Vancouver Sun journalist Sam Cooper published a series of stories that exposed the practice of the River Rock casino accepting hundreds of thousands of dollars in suspicious cash from wealthy gamblers.

These “whale” gamblers would borrow funds to cash in as casino chips from private lenders in Richmond, whose links to organized crime were then under investigation by the RCMP. According to the British Columbia Lottery Corporation, 10 per cent of money circulating in B.C. casinos, or $176 million originated from suspicious currency transactions from 2014 to 2015. The B.C. government announced a review of casino anti-money laundering practices in late September.

Staff may not have been aware of the scale of criminality at the River Rock until the negotiations were nearly complete.*

When I spoke to him in February, Watson was surprisingly patient about the length of time he had spent in bargaining. He had heard that workers at the Grand Villa Casino in Burnaby had taken 13 months in their last round of negotiations, while another casino had taken three years. He felt that his co-workers in the kitchen were ready to strike, and was almost resigned to this outcome.

“When I talked to the managers – sometimes we’ll meet each other in the cafeteria – we both know what is going to happen. We’re going to ask for our raise, and then they’re going to say no, and we’re going to strike,” he says with a laugh.

*Editor’s note: The information about the agreement reached on September 25 and about the casino’s practice of accepting thousands of dollars in suspicious cash was reported after this issue of Briarpatch went to print and thus does not appear in print. The story was updated online to reflect this development.