“North or South?” Most Koreans in the diaspora get asked this question at least once. I’ve often been asked right after a stranger discovers I’m Korean. “I’m South Korean,” I’ve answered dozens of times.

Sometimes I’ll give a more complete explanation when I’m feeling generous with my time: “There aren’t many North Koreans outside of the Korean peninsula.”

The question-asker oohs and ahhs, and follows with a well-intentioned reply: “My daughter loves K-pop.” “I love Korean dramas.” “I want to go to Seoul one day.”

I know that this is a question I’ll never escape, not while the peninsula remains divided. But when I answer “South” and the question-asker responds positively, I think of my North Korean kin, and the response I might get if I answered “North.” As I talk about Korean music and TV, I can’t help but feel like I’m disavowing half my people and homeland.

***

Answering this question has always been uncomfortable. I remember the first time I was asked “Are you from North Korea?” It was in gym class in Grade 5, five years after I’d moved to the United States. I was fluent in English by then, and a loud, bossy girl on the student council. To keep up my reputation, I knew my answer had to ooze confidence. I rolled my eyes and smirked: “Ew, what? Of course not,” drawing out the “O” sounds in my valley-girl accent. I didn’t know much about North Korea, but my instincts told me I had to distinguish myself from those bad, weird Koreans. An emphatic “no” was the only acceptable answer.

A few years later, in middle school, classmates asked, “why do you have the same name as a crazy dictator? Are you related to him?” Half the Koreans in our grade had the last name “Kim” and, together, we laughed off the question. It was a performance, and we were playing our parts.

Growing up, my knowledge of Korean history and North Korea was very limited. I didn’t know any North Koreans except for those I saw on the news. I knew that Korea was split in two, and that the North was ruled by a dictator who wore drab grey suits and lived in a sprawling palace. But I didn’t know why the Korean people were divided, why we had different governments, or why I hadn’t met any North Koreans.

On some level I understood that all Koreans are historically, culturally, and ethnically the same. But North Koreans sure didn’t look like the Koreans I grew up with in Seoul; they wore olive-green uniforms and spoke Korean in lilting tones that sounded more like Mandarin. On the news, I heard that the North was the “axis of evil,” that North Koreans were “brainwash[ed] children in cult of the Kims” and Kim Jong Un was possibly “the world’s most dangerous man.” I learned to associate the North with footage of Kim Jong Un conducting military tests, to respect South Korean soldiers standing off with North Korean soldiers at the demilitarized zone, and to pity the defectors from the North shedding tears as they recounted their escape routes. I absorbed these ideas about North Korea as a far-off, dystopian place before I was old enough to really understand the politics and history of my homeland. Only later would I learn that South Koreans like me and my family were red-baited into rejecting half our people.

My grandparents were born in the final years of Japan’s 35-year occupation of Korea. Immediately following liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, one half of a people was instructed to hate the other half by the Soviet Union and the U.S., turning parent against child, teacher against student, friend against friend.

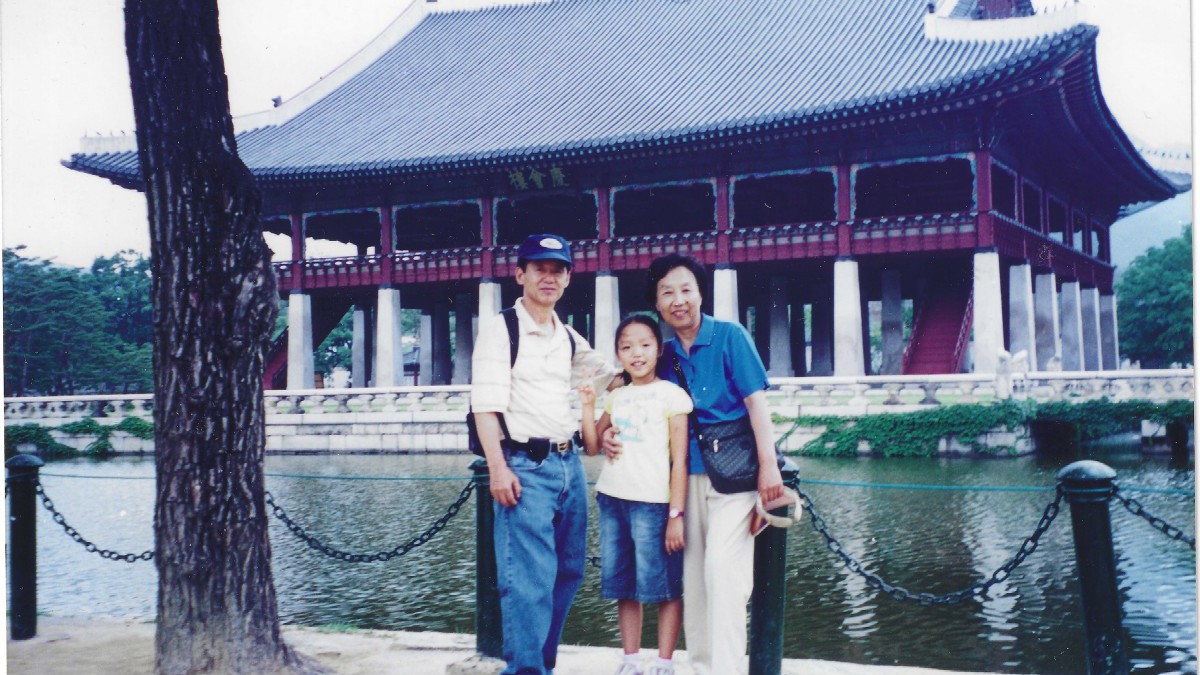

To my grandparents, a divided Korea felt inevitable. They did not even long for reunification because they, like most people in the country, were just trying not to starve during and after the Korean war. The next generation, my parents’, grew up performing military drills to prepare for a looming North Korean attack. In middle school, my mother learned to administer first aid and my father how to assemble and disassemble rifles. When the monthly test air raid sirens went off during the school day, students hurried to crouch under their desks. If they were at home, they knew to draw the curtains tightly so no light would escape into the night and lead police to pound on their doors. After college, my father started his compulsory military service, which was reduced from two years to three months because he’s an engineer. As newly militarized subjects, they followed the South Korean and U.S. government’s orders: the North, formerly our kin, became a fearsome enemy. These ideas were then passed onto me during my early years in Seoul and reinforced by Western media after I moved to the U.S.

***

Only later would I learn that North Korea was never our enemy; the peninsula was divided because of U.S. imperialist interests. On August 6 and 9, 1945, the U.S. dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing over 100,000 Japanese people and tens of thousands of Korean forced labourers. On August 10, 1945, American colonels Chris Bonesteel and Dean Rusk, who knew little about Korea, divided the country by pointing at a line on a National Geographic map.

On August 15, 1945, the Japanese surrendered and relinquished Korea from its colonial rule. Korea was divided between the Soviet Union-backed government to the north, and the U.S. controlled-government in the south.

On June 25, 1950, when North Korean troops invaded the south, the U.S. sent their own forces to push back on their military advances. The Korean peninsula became the site of the first proxy Cold War battle.

Over the next three years, the U.S. carpet-bombed North Korea and killed 20 per cent of the North Korean population during what the U.S. now calls “The Forgotten War.” It deployed napalm on Korean civilians, which burned through their skin to the bone. Later, the U.S. would use napalm again, this time against people in Vietnam. By the end of the war, five million Koreans were killed and 10 million separated from their families by the 38th parallel. Many didn’t know whether their loved ones were dead or alive.

Though an armistice was signed in 1953, with no permanent peace treaty the Korean War is still technically going today. The U.S. uses South Korea to establish military bases and ramp up drills in its new Cold War against China. The U.S. government vilifies North Korea for their human rights violations and nuclear weapons development, while isolating the country through sanctions that make life more difficult for North Koreans. The sanctions have created what scholars have described as the world’s most-forgotten food insecurity crisis because of the lack of news coverage.

***

Korea is one of few countries in which both sides prohibit the other’s citizens from setting foot on their soil. North Korea is the only country that the U.S. government bans me from entering as a U.S. citizen. For Korean-Americans who come from the south like me and my family, I wonder if we will ever be able to go to the other half of our homeland or know the other half of our people.

North and South Koreans are the same people; the peninsula and its people are not supposed to be divided down the middle. Every time I proclaimed to be from the South and renounced the North, a pang of grief ran through me. Why, I could not say. To reject my own people inflicted a pain that I did not recognize until many years later.

How would I answer the question “Are you North or South Korean?” now? The narrative I was sold about my own people and the U.S. – North Korea as the axis of evil and America as a benevolent saviour – no longer stands. I can no longer answer “South Korean” like I used to. My grandparents, who are old enough to remember a single Korea, shake their heads in resignation when I speak of reunification. Unlike my grandparents, perhaps because I cannot remember what they know, I now organize toward permanent peace on the peninsula. I fall asleep at night dreaming of our people joining hands at the 38th parallel and being whole once again. I now have a different answer, one that feels truer to me: I am neither from the north or south – I am Korean.

*This essay was the winner of the creative non-fiction category of our 13th annual Writing in the Margins contest, judged by Helen Knott. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Regina Public Interest Research Group (RPIRG) for this year’s contest.