“There is no better friend to Israel than Canada. We shall always be there for you, and in front of you.”

– Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird, Jerusalem, January 2012

Canada’s support for Israel has a long history, dating back even before Israel was founded. In fact, it was Canada’s own Lester B. Pearson who chaired the United Nations committee that recommended the partition of Palestine and the creation of Israel in 1947. Still, there is little question that the diplomatic, military, and economic ties between the two countries have deepened in recent years, coupled with a concerted campaign to stifle criticism of Israel.

The Canadian government’s unbending support for Israel is well known, especially within Palestine solidarity circles across Canada. What is less understood is the basis for this support. While economic and geopolitical ties are certainly important factors, the shared history of Canada and Israel as settler societies is crucial to understanding Canada’s ongoing support for Israel. Simply put, both countries were founded on the forced displacement of Indigenous peoples and the theft of their lands and resources. And in both cases, these colonial processes continue to the present day.

The similar nature of Canada and Israel as settler societies not only serves as a solid foundation for ideological affinity, but is also the basis for shared interests in the realm of international politics as both countries contend with ongoing attempts by their Indigenous populations to seek justice and redress on the world stage.

Providing a playbook

Canada’s support for Israel has taken many forms, but perhaps its greatest gift has been a real-life how-to guide for establishing and maintaining a settler society that includes an array of strategies, tactics, and programs for taking land, subjugating Indigenous populations, and weakening their resistance. It’s also worth noting that many of these tactics and strategies were used by the South African apartheid regime, including the Bantustan system and the use of the Dom Pass to restrict the movement of black South Africans.

The Indian Act of 1876 must be seen not only as the centrepiece of Canadian colonial policy towards Indigenous peoples, but also as a blueprint for apartheid. The Indian Act enshrined completely unequal rights, relations, and – over time – vastly disparate living conditions between Indigenous peoples and Canadian settlers. It also represented a policy of extermination as it facilitated the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples, and deprived Indigenous nations of their right to decide who was and was not “Indian.” This was a very gendered process as different standards for retaining “status” were applied to Indigenous women as compared to men, resulting in vast numbers of Indigenous women and their descendents losing not only their recognized status as Indigenous peoples, but also their ability to remain in their communities.

Israel has long engaged in attempts to regulate Palestinian identity, such as granting Palestinians within its borders Israeli citizenship while designating them “Arab Israelis,” issuing a complex array of different ID cards to Palestinians in the occupied territories restricting where they can reside and travel, or gradually stripping residency rights from hundreds of thousands of Palestinians with ties to the West Bank and Gaza.

Canada’s reservation system was also central to the displacement and containment of Indigenous peoples. In most of what is now Canada, the federal government can point to treaties as affirmation that the land was occupied with the ostensible consent of its Indigenous peoples, though there are also areas, including the majority of British Columbia, where colonization and the establishment of reserves took place with very few treaties. This process is one that continues to this day in a number of ways, most notably in B.C. with what’s referred to as the modern day treaty process, in which the only accepted framework for negotiating treaties is through permanent extinguishment of inherent land rights in exchange for fee-simple reserve lands.

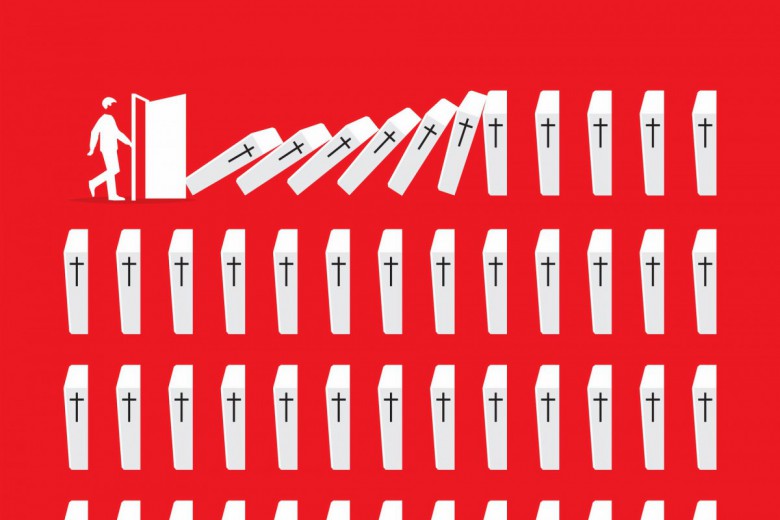

Israel’s process of colonizing Palestine followed a similar strategy of forced displacement coupled with containment. Gradual settlement began in earnest during the first decades of the 20th century, culminating with the 1948 Nakba (the Arabic word for “catastrophe”) which saw the displacement of over 750,000 Palestinians from what then became the state of Israel. This process of land theft deepened after 1967 with the expansion of Jewish-only settlements in the occupied territories, a process that continues to the present.

Controlling the movement of Indigenous peoples has also been central to both Canadian and Israel colonialism. Canada’s pass system, enacted in 1885, dictated that Indigenous peoples required written permission, including their reasons for leaving, from the local Indian agent to leave their reserves. The pass system was put into place during the North-West Resistance and was justified by the Canadian government as a means of monitoring Indigenous peoples who were potentially participating in or supporting the resistance. Though initially described as a temporary measure, the pass system was used against Indigenous peoples at least until the 1940s.

This model of restricting the basic human right of Indigenous peoples to mobility within their own lands lives on today in Palestine. This includes an elaborate system of permits, checkpoints, and the apartheid wall, which together restrict and regulate the movement of Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. This is accompanied by the hermetic siege of Gaza, the most extreme expression of controlling movement between and within Palestinian reserves.

A further strategy that Israel has borrowed from Canada is the use of seemingly endless negotiations as a deliberate stalling tactic and a means of further entrenching the control of Indigenous lands and resources. Negotiations also take place in a context of vast disparities in power and, to varying degrees, overt threats of violence. For example, when Treaty 7 was negotiated between the Canadian government and representatives from the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Tsuu T’ina nation, and a number of Nakoda and Assiniboine communities, the representatives of the Crown brought a sizable contingent of North West Mounted Police, who pointed their cannons directly at the Indigenous encampments and occasionally fired at them as a show of force. In an oral account of the signing of Treaty 7, Stoney Nakoda elder Morley Twoyoungmen recalls: “The chiefs said, ‘You talk of peace while there are guns pointing at me. This is not peace, please lay down your guns.’”

Israel has also employed the tactic of negotiations with similar success, at the expense of the Palestinian national movement. Throughout the Oslo Accords, the Road Map to peace, the Annapolis conference, and countless other “peace processes,” Israel has continued its expansion of illegal settlements and brutal wars against the Palestinian people. At the same time, the most basic demands articulated by the Palestinian movement (ending the occupation, allowing refugees to return to their homelands, and recognizing equal rights for Palestinian citizens of Israel) are invariably outside the parameters of negotiations.

Fates bound together

This shared colonial history is crucial to understanding Canada’s support for Israel. The similar nature of the two states creates a solid foundation for ideological affinity wherein, from the Canadian standpoint, there is nothing particularly problematic or controversial about a predomin-antly European population establishing a state on the lands of racialized people, displacing the original inhabitants, and settling the land as their own. In fact, Israel is often celebrated as an “outpost of civilization” in much the same way that the colonization of Turtle Island (North America) was justified as a “civilizing mission.”

Canada and Israel also have shared interests that are somewhat unique to settler societies. The legitimacy of both nation states is regularly challenged by the continued survival and resistance of the Indigenous inhabitants of the lands to which these states lay claim. With the perseverance of the Palestinian struggle and international growth of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, challenges to Israel’s “right to exist” as a colonial apartheid state have gained mainstream prominence, but it’s important to note that Canada also faces significant challenges from assertions of Indigenous sovereignty. The ongoing struggles in B.C., where the provincial government has had to acknowledge that the vast majority of the land is unceded, provide but one of the more clear examples of challenges to the very legitimacy of Canada’s territorial jurisdiction.

In the realm of international politics, Canada plays the role of a proud and uncritical defender of Israel against attempts to address any of its numerous human rights violations or war crimes. Canada has its own interest in ensuring that Israel maintains impunity as it has also come under scrutiny at the UN, which is increasingly used by Indigenous peoples as a forum through which to advance their struggles and seek redress for human rights abuses. Canada has also garnered international attention over its ongoing expansion of the tarsands in Alberta, its continued export of asbestos to the Global South, and the atrocious record of Canadian mining companies in regards to human rights abuses and displacement of (predominantly Indigenous) people in Latin America. If Israel is held accountable for its crimes against Indigenous people on the world stage, Canada has a greater risk of meeting the same fate. It can’t allow these precedents to be set, and thus it benefits from ensuring that the UN and its various bodies are kept weak and unable to uphold international law.

A recent example of this is Canada’s continued fear of being held accountable for the residential school system as a crime of genocide. According to a recent article in the Globe and Mail, the Conservative-appointed chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is conscious of this concern: “Justice Murray Sinclair says the United Nations defines genocide to include the removal of children based on race, then placing them with another race to indoctrinate them. He says Canada has been careful to ensure its residential school policy was not ‘caught up’ in the UN’s definition.” As Judge Sinclair explained to a group of students at the University of Manitoba in February, “That’s why the minister of Indian Affairs can say this was not an act of genocide … but the reality is that to take children away and to place them with another group in society for the purpose of racial indoctrination was – and is – an act of genocide and it occurs all around the world.’”

The Canadian government also benefits from its relationship with Israel by gaining access to Israel’s experience with tools of repression either for domestic use or, in the case of Israeli drones, in Afghanistan. Though Canada has developed its own vast experience in this regard through repeated police and military deployments to subdue Indigenous resistance, Israel has much to share in the way of high-tech means of policing and intelligence gathering developed over decades of repression and warfare against Palestinians. In addition to more overt forms of violent repression, this also includes the repeated use of the “terrorism” label to try to discredit the Palestinian movement, a label that is now increasingly used by the Canadian government in its propaganda wars against Indigenous peoples and, recently, to smear both Indigenous and non-Indigenous opposition to the tarsands and its associated pipeline projects.

Canada’s desire for Israel’s expertise in matters of repression underlies the 2008 Canada-Israel Declaration of Intent to enhance co-operation on public security issues, a document signed by representatives of both governments that outlines Canada and Israel’s “common threats” and details a “shared commitment to facilitate and enhance cooperation” in areas ranging from border security to correctional services and “terrorist financing.”

Unity and solidarity

For Indigenous peoples living in Canada, the principle of unity and solidarity between peoples has often been crucial in continuing their struggles as people of many nations all living on Turtle Island. This unity has been extended to include the Palestinian struggle since at least the 1970s when the American Indian Movement and the Palestine Liberation Organization issued a joint declaration affirming “united resistance to a common form of oppression.” These connections must continue and be deepened as our different experiences of resisting Israel and Canada help inform each other.

For Canadians working in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle, it must never be forgotten that Indigenous people here are struggling every day to survive the numerous ways in which Canadian apartheid continues to damage the original peoples upon whose land this country was built. It is not simply a matter of moral consistency, though that is of course important. Struggles for Indigenous sovereignty are unique in that they directly challenge the hegemony of Canadian capitalism. For that reason, it is important to bear in mind how supporting Indigenous self-determination will benefit all struggles for social justice within Canada in the long term. Furthermore, coming to terms with what it means to be a part of a settler society in Canada, and the resulting ramifications for both Indigenous peoples and settlers, can only make our ability to support the Palestinian struggle stronger.