Antonia

Directed by Tata Amaral

Coração da Selva, 2006

In much of the world, when a woman steps outside the home to do anything other than the daily shopping—when she declares herself free to pursue her own dream—she becomes a radical. For the poor women of the world, pursuing another way of life, seeking something beyond the family circle of which they are the diligent center, is riskier still. Brazilian director Tata Amaral’s latest release and third feature film, Antonia, features women who know about the risks of declaring this freedom.

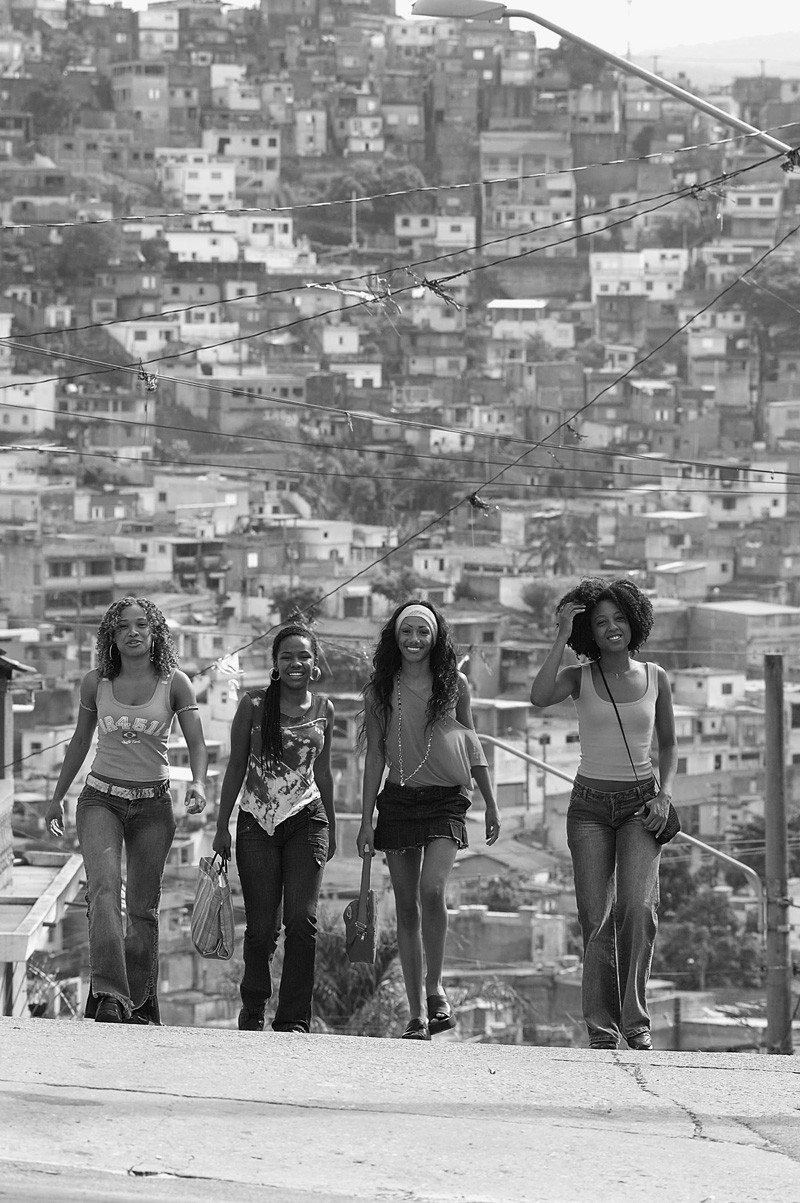

Preta, Barbarah, Lena, and Mayah, four young singers from the slums of São Paulo, strive to earn a living as a rap group. They are all, however, bound to men who impede their collective dream, obstructing in expected ways as deadbeat philanderers, condescending controllers, and hateful criminals. Although structured with a familiar narrative arc (conflict, crisis, resolution), the film begins with the promise of a rags-to-riches tale, then quickly quashes it, instead taking viewers on a reality tour of life for women at poverty level.

Shot in super-saturated colour and edited at a crisp pace, Antonia contrasts the overt violence of life in the slum with the tranquility of everyday life. Antonia’s subtle moments reveal the duress and distraction of the women’s daily existence. A mother’s criticism is quietly endured in exchange for free childcare. A horny boyfriend takes precedence over rehearsal. An injured brother, his leg in a cast, must be hefted up several flights of stairs. Sneakers replace sexy high heels for the trek home up the slum’s steep hill.

Amaral succeeds because she understands the struggles of working in a male-dominated industry. (Antonia, which opened commercially in Brazil in February, competed in both the Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo film festivals as the only female-directed fiction feature.) Antonia also benefits from the contributions of the largely nonprofessional actors who developed the colloquial dialogue of the film in pre-production workshops.

This practice has become commonplace in Brazil’s emerging cinema of the morro (literally “hill” where many of Brazil’s slums are located, and synonymous with the neighborhoods). Filmmakers with means, like Amaral and her male counterparts, including Fernando Meirelles (director of City of God and executive producer of this film) and Walter Salles (Central Station), are seduced by the rich vein of stories untapped among the poor and working class. Nonprofessional actors are included in the cast to add authenticity to the final product, but the stories are essentially mined by outsiders. That Amaral taps this story of marginalized women is laudable. That the women of the morros are someday able to tell their own stories would truly be the radical act.