“I should have remained academic and abstract but for the war.” -Bertrand Russell

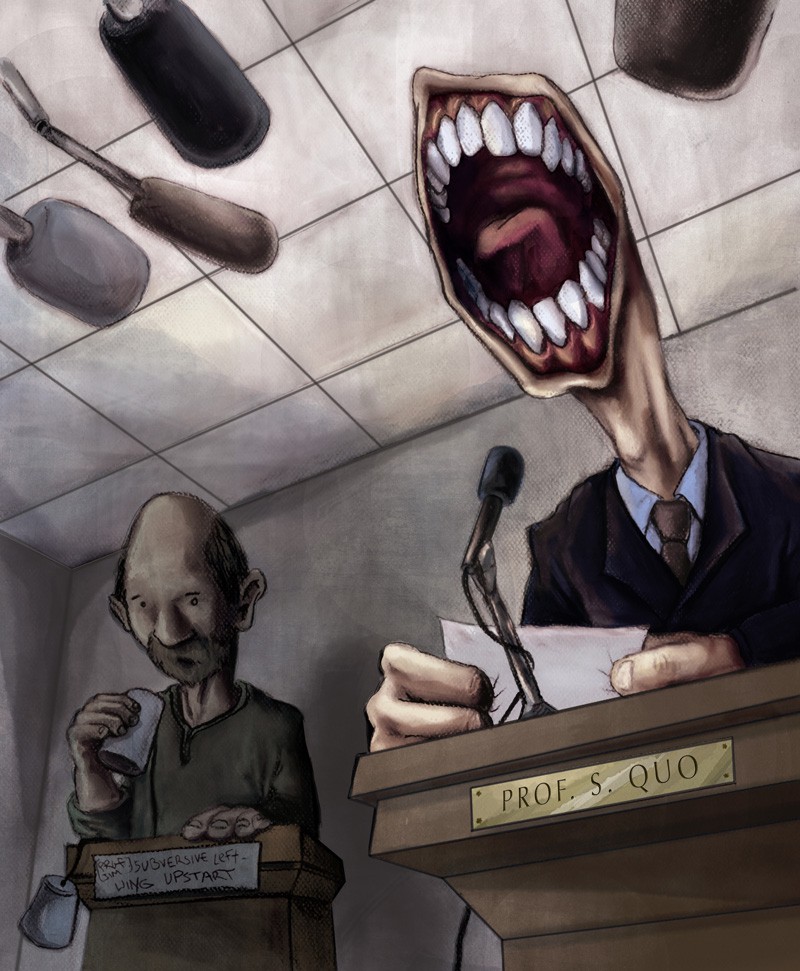

At last fall’s University of Toronto conference on academic freedom, Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Teach, James Turk, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, offered some useful reminders about the intersection of schools with free expression. The concept of academic freedom, he pointed out, is a convention without hard supports in law, including at the university. It is contingent and discretionary. High schools are organized around obedience, not awareness, and while colleges and universities have some free speech protections under the Charter, only collective agreements can link academic freedom to job security. Without strong collective agreements, universities will remain elite institutions, disguising power as knowledge while constraining the individual voice within a narrow range of accepted opinion.

Turk cited the example of Bertrand Russell to illustrate his point that the individual, dissident voice, no matter how well-secured or courageous, must ultimately depend on a collective strategy to ensure its academic freedom. Scion of a wealthy aristocratic family – his grandfather, Lord John Russell, was prime minister – Russell became a social activist. Despite Russell’s glittering reputation in mathematics and philosophy, Cambridge University sacked him in 1916 for his support of conscientious objectors to the First World War. When patriotic mobs attacked meetings where he spoke, the government left him unprotected; when he refused to pay a fine, the government sold his rare mathematics books. Finally, in 1918, as a result of publishing an article in the pacifist weekly The Tribunal, he was sentenced to six months in prison.

In his article, Russell had speculated that a delayed peace might bring an American army of occupation to England. Its contribution, he surmised, would be “intimidating strikers,” as that was the army’s chief occupation at home. The sentencing magistrate found this opinion to be “very despicable,” his article an offense against “all sense of decency.”

Russell’s manners did not improve after his release. His view that extramarital sex was moral if based on love cost him his position at the City College of New York in 1940, a decision the courts upheld. In 1961, at the age of 89, he spent a week in jail for anti-nuclear protesting. In 1966, he organized (with Jean-Paul Sartre) an international war crimes tribunal condemning the Vietnam War and, in particular, American atrocities, including “extermination.” This was three years before the massacre at My Lai.

Two days before his death in 1970 at the age of 98, Russell issued a statement decrying the “spectacle of wanton cruelty” of foreign-sponsored Israeli aggression. He argued for the “right of return” of Palestinian refugees and for a two-state solution based on pre-1967 borders.

The account of such staggering, knowledge-based activism is made all the more impressive by the steadfast, unending resistance to it mounted by the universities, governments, and the mainstream media. Forty years later, we seem to be no better off. Iraq, Afghanistan, Colombia, Zimbabwe, Burma, Israel, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo – predator and prey, the Great Game rages on. The well-funded metanarratives of our time – the war on terrorism, the clash of civilizations – suffocate public debate.

So does academic freedom have any meaning today? Can a butterfly find air if it is trapped behind a classroom window? Why is it so difficult to convert the best ideas into action in the real world?

Two months after 9/11, Lynne Cheney, wife of Vice-President Dick Cheney, released a report entitled, “Defending Civilization: How Our Universities Are Failing America.” Prepared by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, an “educational non-profit” based in Washington, D.C. “dedicated to academic freedom,” it castigated the “many faculty” who declined to call “evil by its proper name.” Reading through the citations provided as evidence of this supposed crime, we see those she has labelled unpatriotic offering only restraint and moderation against an American foreign policy response seemingly based on blind revenge.

The jingoistic crudity of Cheney’s report is hardly surprising. Indeed, the backlash against dissident intellectuals was well under way in the 1980s, and ramped up through the neo-liberal ’90s. Independent ideas and their authors were increasingly cut off from research support, which was more and more tied to private capital. As Nancy Olivieri, a medical researcher for the University Health Network in Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, discovered in 1996, such money is not disinterested. The drug giant Apotex threatened legal action if she sought to publish her findings about the experimental drug deferiprone. The University of Toronto and the hospital initially sided with Apotex.

Following 9/11, a kind of McCarthyism resurfaced on American campuses. Its most offensive form was Campus Watch, a website founded in 2002 that asks students to report professors critical of American foreign policy in the Middle East. It cast a wide net. Douglas Giles, an inoffensive, “˜60s-style philosophy professor, was fired from Roosevelt University in 2006 for permitting a Muslim student to ask a question about Zionism in his World Religion class. Elsewhere, the unflinching Norman Finkelstein, bête noire of the Israel Lobby, was denied tenure at DePaul University on the spurious grounds that his scholarly works were “controversial” outside the university.

The Palestine issue has clearly been a test for universities. As distinguished scholars John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt note in their bestselling book, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, universities have been under tremendous pressure to block debate and activism around Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. And university administrations have tried to comply. Canadian university presidents issued a statement in the summer of 2007 opposing the Israeli boycott/divestment/sanctions campaign that had recently been launched. Students and faculty, outraged at such muzzling, forced a public debate at Ryerson University on the subject in November 2007 that drew 600 people. Similarly, students at McMaster University helped force the university to retract its attempted censorship of the phrase “Israeli apartheid” to describe the systematic oppression of Palestinians in the Occupied Territories through separation and the creation of a dual society within Israel itself. When the University of Toronto overzealously referred the same phrase to the Toronto Police Hate Crime Unit, the police found no basis for classifying the term as hate speech.

It is, of course, ironic that the police should have to tutor a major university on academic freedom. A political lobby with a geostrategic interest based on race should have no power to cause an independent organization, let alone a major university, to participate in such inanity. But it does.

My own organization, the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, provides an interesting case in point. When our Toronto local, District 12 OSSTF, was asked by two of its members to consider responding to a call for solidarity from Palestinian teachers and other unionists in December 2006, our union came under a blistering national media attack similar to what CUPE Ontario endured in June 2006 when it passed a resolution at its annual meeting in support of an Israeli boycott campaign. The attacks were orchestrated by the advocacy organization B’nai Brith, quietly supported by the Canadian Jewish Congress (neither of which represents, incidentally, the sentiment of the many progressive Jewish organizations in Canada and Israel that stand for human rights).

On the day set for the debate, the Jewish Defense League set up an aggressive picket as our members arrived. The police were in force nearby. But the debate did not occur because an obstructionist motion was introduced by pro-Israel activists that consumed the meeting time, leaving only five minutes to debate motions that had drawn a crowd and brought national ridicule to our union.

What would have happened if the majority of the delegates – neither Israel lobbyist nor Palestinian activist – had been allowed to hear a full debate on the key motion proposed? It was a tame enough proposal. It asked that the teachers’ federation local receive the November 2006 Amnesty International report on the Occupied Territories, endorse its recommendations, and refer it to our provincial human rights committee for the purpose of educating our members and supporting human rights groups in both the Occupied Territories and Israel. The motion had the enthusiastic support of both the Amnesty International Secretariat in the U.K. and of John Dugard, the UN Special Rapporteur for the Occupied Territories – but not of the Canadian Jewish Congress, whose Ontario regional director, Len Rudner, politely explained to the author in an email that the Amnesty International report was “discredited” because it presented only the “illusion of balance [and] fairness.” He recommended NGO Monitor, an Israeli Defense Forces-staffed NGO watchdog, as the more trustworthy source on the subject of respect for human rights in the Occupied Territories.

~

Pushing back against such inanity is important. We can be relieved that Parliament was loud in its indignation when Stephen Harper suggested in May of this year that criticism of Israel was anti-Semitic. But the trend toward silencing institutions and voices within our democratic society is nonetheless disturbing, as both the OSSTF and university examples illustrate.

The role of the mainstream media as filters for legitimate opinion is a major structural limitation on free debate, as the CUPE and OSSTF experiences show. Unions are much easier to demonize than universities, though, so subtler methods are employed to control the dissident academic voice. For example, “good intellectuals” are embedded in positions of regular commentary, while resistant intellectuals, on those occasions when for the sake of “balance” they might appear publicly, are subjected to critical or skeptical handling by interviewers. This bias in favour of the status quo has an “abnormalizing” effect. Students come to university unprepared for and unable to process alternative views. As a result, the critical professor appears suspect or alien.

Critically minded university and college instructors face formidable structural limitations within their institutions as well. The most obvious one is tenure itself – who gets it, and who doesn’t. According to Sedef Arat-Koç, a professor of politics and public administration at Ryerson University, one of the impacts of having to position yourself for this coveted job guarantee is self-censorship, the internalization of values and positions that you may find distasteful. For those unable or unwilling to bend, a second, more visible impact is the “racialization,” as Arat-Koç calls it, of the non-tenured teaching pool. In other words, if you are among the presently oppressed or the formerly colonized – Inuit or Palestinian, Caribbean or Filipino – chances are good that you will have an alternative perspective, and more than good that you are not white. In the absence of meaningful university policies on academic freedom, all such individuals must rely on their unions for protection.

It is an irony, perhaps, that the union hall, that crucible for upholding the dignity of ordinary working lives, should also be the best recourse for upholding dignity in the ivory tower. Unions have it hard, of course. Unfettered capitalism has devastated union density and, with it, the quality of life in the United States. Canada has fared much better, but globalization and free trade have enlarged the opportunities for privatization (greed) to intrude upon union density here and therefore upon the big public service areas – in particular, health and education.

At the same time, we have the positive example of a strong and prosperous Scandinavia, where union density is high. Norway is the outstanding model. In addition, the International Labour Organization and the International Trade Union Confederation have established strong norms and practices for coping with the excesses of globalization. Indeed, the ILO was cited as a critical source in the landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Canada in June 2007 – the B.C. Health Services case – which declared that collective bargaining was protected by the Charter under freedom of association rights. That offers some constitutional headway toward entrenching labour rights as human rights, and thus some protection against generally hostile provincial legislatures.

But as the OSSTF example shows, it remains important that provincial and national union memberships reach beyond Canada’s borders to connect with the movement for international solidarity. That means educating members more broadly on issues of social justice so that the obligations of international solidarity are felt strongly and the trails of money that lead to graves and prisons in the Global South are exposed. Support for a Coca-Cola boycott in order to protect union organizers’ lives in Colombia should not be unduly hampered by a parochial focus on contracts at home to the exclusion of all else.

Contracts between worker and employer based on negotiating from mutual positions of strength (and after much struggle and bloodshed to get there) are without a doubt the first great achievement of unions as a social justice actor. They are also precursors of the human rights sensibility, establishing work as a measure of common humanity, blind to irrelevant differences, subject only to standards of decency. The way forward from here, particularly in North America, involves understanding the continuing threat from capitalism and reaching out to others, even if only to protect ourselves. Without an international social justice sensibility, without a far-reaching solidarity, unions cannot hope to cope with the CEOs and the politicians who serve them. And without the sort of education and debate universities were founded to foster, a coherent social justice sensibility cannot be attained.

The current state of the university in North America is for that reason all the more alarming, all the more in need of the community-based skills of the union movement. The disjuncture between the university and the field of labour, which is the living world, is exacerbated by the failure of the university to give force to its own ideals. It is a recipe for generalized social dysfunction, made all the worse if the union movement itself narrows its organizing and debating prowess to achieving only small objectives.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be this way. In Latin America, universities have a much stronger tradition of critical social commentary and are in touch with and supported by unions and human rights actors. The Bolivarian movement owes much to this critical infrastructure for the transmission of ideas. Even military education – as Hugo Chavez demonstrates – can provide perspective and analysis on economic and social reality. The South American leftward shift is possible because everyone from peasants to professors understands how the World Bank and International Monetary Fund operate.

Compare Canada’s public discourse on our involvement in Afghanistan or Colombia. When was the last time you overheard a conversation at Starbucks on the Western project to build a pipeline from Kandahar to Pakistan? And did you hear on the CBC, in the classroom, or on the assembly line that Colombia is top of the charts for state-sanctioned murders of union and human rights activists, year in and year out? Did you hear it at all?

Perhaps we don’t need academic freedom. The Internet, still unregulated, is a sign that such knowledge and critique can be organized and distributed broadly from outside the perimeter. Thanks in part to this medium, Barack Obama circumvented Democratic machine politics and may yet be able, if elected, to effect a major shift in political sensibility in the United States. And there are hopeful signs here at home. Liberal leadership aspirant Bob Rae, member for Toronto Centre, has publicly expressed his opposition to military recruitment in our schools. That’s good for kids.

But the kids have their opinions, too. Being a high school teacher, I was heartened by a Toronto Star report on June 2, 2008 that about 40 students from St. Mary’s Secondary School in Cobourg, Ontario, had formed a group called Kids for Khadr. They were demonstrating outside the U.S. consulate in Toronto, protesting, petitioning, and singing. Their placards challenged policies of torture, the “gulag at Guantanamo,” and Canadian failure to respect international law and protect a Canadian citizen.

Universities, politicians, and pundits – take note. You don’t have to be Bertrand Russell to see and state the truth. But without legal protections and union supports for those who do, without solid ground on which to act, truth remains elusive, the individual abstract, and freedom academic.

Roger Langen works as the Human Rights Officer for the Toronto local (District 12) of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation. He has written for various periodicals, including the CCPA Monitor, in which an earlier version of this article appeared.