Correction (noun): The act or process of correcting something; a change that rectifies an error or inaccuracy.

I have been imprisoned in Pine Grove Correctional Centre in Saskatchewan several times over the past 10 years. I have fought many battles for fair treatment over those years; won lots, lost some. Every day I work to help myself and the other girls, all of us dealing with correctional officers’ (COs) abuses of power within a corrupt system. I write several pages every month for the inmate committee meeting in an attempt to catch things COs think they can get away with doing because they believe no one is paying attention.

The requirements for becoming a correctional officer are low in Saskatchewan – in some cases, it takes just nine weeks in a training program. Saskatchewan Polytechnic also advertises a two-year diploma course in correctional studies – but that is not always necessary to be a correctional officer. I know this because there are some staff working at Pine Grove, where I am being held, who did not take this course. The course overview starts by saying, “Consider the benefits of a career in corrections. One, you’re helping offenders make positive changes in their lives. Two, you’re helping make our communities safer. Three, you’re earning a great salary. Four, your skills are in demand.”

I find the opening statement of “helping offenders make positive changes” offensive. Controlling every aspect of our existence with rules that have no value in everyday society is not helpful. I feel defeated by the unwritten code of conduct that is the reality in these facilities.

I write several pages every month for the inmate committee meeting in an attempt to catch things COs think they can get away with doing because they believe no one is paying attention.

Correctional officers are not counsellors, and they certainly shouldn’t be. They are not capable of dealing with people who are broken and hurt. They constantly disrespect and manipulate us into believing that we have no rights other than food, water, and shelter. They regularly abuse their authority for no reason other than that they are wearing blue shirts and having a bad day. We wear grey, making us a visible target for their abuse. They find ways to justify their temper tantrums – including passive aggressive behaviours such as ignoring us when we ask for our trays, our beading needs, or our canteen items. We walk on eggshells because of their empty threats of not giving them to us at all if one person oversteps a boundary. When you have been here long enough you realize the power they do not have and the mind games they use to gain power.

These are some of the things I have experienced at the hands of correctional officers, since the beginning of my time in prison – by now, my longest standing relationship:

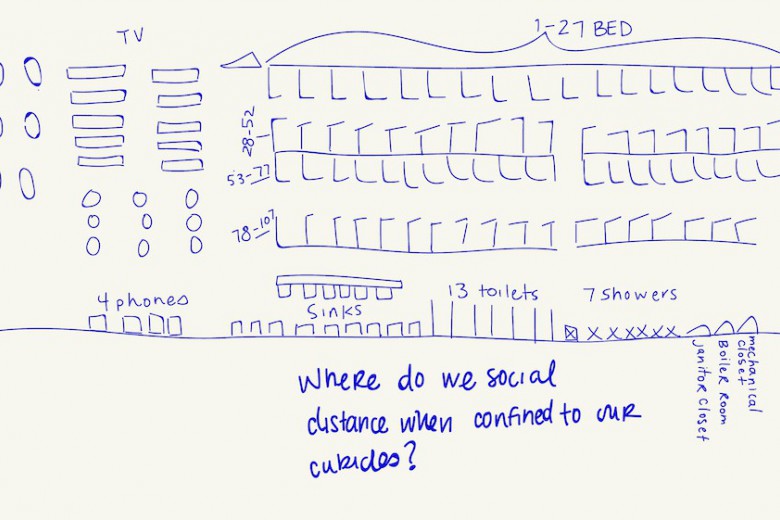

Excessive segregation. I have spent months on a unit where I was locked up for 23 hours a day. I should have been in a regularly functioning unit, where I could have had between four and 14 hours a day out of my cell. The justification for this decision was that there was “no room” anywhere else.

I’ve been written up for things that even Kris Kringle wouldn’t be able to classify as naughty. The write-ups are one-sided and can’t possibly have any factual evidence to support them. For example, one time everyone was yelling and being disrespectful to the staff from inside their cells, but only one other person and I were punished and forced to stay locked up, even though I had been sleeping and had said nothing at all. It doesn’t matter whether they have the right or wrong person. As long as someone has been punished, they have done their job.

Another time, my desk chair was sprayed with WD-40 lubricant right before I was to be locked in my cell, which has minimal air circulation. When I began getting sick from the fumes, I asked if the door could stay open to air out my cell, and an officer made a joke that they thought I liked getting high. No effort was made to fix the situation.

I have had garbage dumped on my bed by staff doing their search “tours.” The correctional officer who did it thought it was clever to tell the other girls, to make sure I knew who did it.

I have had all my belongings ripped down and taken from me for having an “excessive amount of stuff,” when in fact I had significantly less than any of the other 22 girls in the unit.

Eating the meal that doesn’t belong to you or missing a set of clothes when you only get four clean sets for the week may seem insignificant, but when all you get is the minimum amount to get by, it can make a big difference in your day.

I have lost my job for no reason, gotten it back, and lost it again. The last time, my boss – the placement officer – had a very creative excuse: “You are wrecking the calibration of the washing machines by putting Shout stain remover in the loads.” I recently got the job back by filing a complaint.

If someone pisses a CO off, there go our chances of getting what we are entitled to have – staff regularly short us laundry items or give us the wrong meal tray. Eating the meal that doesn’t belong to you or missing a set of clothes when you only get four clean sets for the week may seem insignificant, but when all you get is the minimum amount to get by, it can make a big difference in your day. Being disrespected and ignored by a staff member results in vendettas and mini wars that are likely to end with someone being moved to a higher security unit or getting a Mickey Mouse charge. Not only did you not get what you originally wanted, you now are in a worse position than you were before asking.

Emotional beatings come in all shapes and sizes in here. Even the smallest form of violence can claim your spirit and motivation, and your inner child goes into hiding. Once our defences are down and we have been wounded a couple of times, more harmful shots get fired. They use what they think they know about us to insult our character.

COs either like you or they don’t. If you are quiet, easygoing, humble, and passive, you might get in trouble sometimes but the staff won’t hold it against you because you don’t question their integrity or their craving for control. But when an inmate is outspoken and knows their rights, COs will do less for them. Often, if a guard does not like you, they will tell you to either ask another officer or wait until the next officer’s shift.

We walk on eggshells because of their empty threats of not giving them to us at all if one person oversteps a boundary.

While writing this article, I figured it would be unfair to share only my perspective of the violence in Pine Grove, so I attempted to ask several different correctional officers for their take. Believe it or not, it’s not a topic that they seemed keen to discuss – few stuck around to let me finish explaining. I got several disturbed facial expressions, a few who “pled the Fifth,” and a couple who went against the grain and weren’t afraid to admit the problems within the ranks of the correctional officers. The question I asked each of those individuals was: Do you see violence happen around you, from your co-workers toward inmates as well as toward each other? Of those who answered “yes,” these are some examples that they gave:

Dangling the carrot in front of the horse. For example, a staff member might tell prisoners, “You aren’t getting the Wii game system today because you guys were being loud last night.” We get the Wii once every two weeks for the day. Meanwhile, the truth is that we didn’t get the Wii because the recreational officer forgot to send it.

Handing over work assignments due to laziness and power dynamics among officers. For example, a CO may assign a new staff member to do a task they don’t want to do, knowing it will create chaos because the newbie hasn’t been trained in that area yet. Senior COs can use the chain of command to make junior staff do their bidding.

Complaining to peers instead of to the person responsible. There are typically specific steps that need to be taken to resolve a situation – but these steps are rarely followed and result in childish tattling and unnecessary reports and discipline.

Violence has consumed the idea of helping people become better; giving people knowledge, skills and options; allowing growth and self-worth.

I feel as though people working in this industry are making money off of other people’s suffering. I find this environment to be just as toxic for correctional officers as it is for inmates. Over the course of my stay here, I have met a handful of staff who come here to do their job and that’s it. They don’t play silly little games or require prisoners to walk on eggshells around them. They treat us with the same level of respect as they would someone outside in the community.

But on the whole, I have watched this environment silently steal little pieces of people until one day there is no more of them left. This will continue to happen for decades to come unless the people who maintain the foundation of the system start digging and see the rot and filth that it has been feeding from – the outdated, broken, unethical, and useless ideas, the irrelevant and demeaning rules we are subjected to in the name of control. Violence has consumed the idea of helping people become better; giving people knowledge, skills and options; allowing growth and self-worth. We are human beings. You cannot put us in a junkyard and expect us to fix ourselves.